Mahmoud Daram

Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Iran

Abolfazl Ahmadinia

Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Iran

Received: 18-09-2014 Accepted: 15-10- 2014 Published: 31-10- 2014

doi:10.7575/aiac.ijclts.v.2n.4p.30 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijclts.v.2n.4p.30

Abstract

This paper intends to argue that Mother Courage, the main character of Bertolt Brecht’s play, Mother Courage and Her

Children (1980), fails to support her children financially because of a socio-psychological state defined by Marx as

“alienation”. Mother Courage’s attempt to maintain and secure financial profit leads to a tragic failure because her

endeavor falls into the Marxist category of alienated labor. This reading intends to offer a study of the two major

aspects of “alienation”– ‘alienation and identity,’ and ‘alienation and political,’– in selected play.

Keywords: Sense of Loss, Alienation, Identity, Estrangement, Capitalism

- Introduction

The concept of “alienation” has a determining place in contemporary studies of human relations and sociological

thought. In a sociological study, “alienation” is the sense of loss felt by an individual’s consciousness when the

individual is faced with an object in the context of capital’s domination. Charles Taylor states that alienation has “an

indefinable sense of loss; a sense that life has become impoverished, that men are somehow deracinated, that society

and human nature alike have been mutilated, and above all that men have been separated from whatever might give

meaning to their work and their lives.”i

The concept of “alienation” is clearly demonstrated as a capitalist production which has linkage to applications

particularly in the areas of personal and political issues. Personal alienation is relevant to the question of identity.

Theoretically, personal alienation has symptoms that can be traced in the conduct of the individual. Mother Courage

shows these symptoms which this study will pinpoint. As a process, personal alienation results in a crisis of identity and

can lead to the individual’s marginality. On the other hand, political alienation is an individual’s feeling that he is not

part of the political process and that his actions make no difference. Since capitalism plays an important role in the

production of “alienation”, Marx offers a theoretical discussion of the devastating effect of capitalist production on

human beings, on their physical and mental states, and on their social processes of which they are a part. Each one of

these aspects– personal, and political– will be discussed in the following.

I intend to utilize the theory of “alienation” maintained by Marx in my argument in two ways: Personal and political.

With regard to personal alienation, Marx offers the symptoms which include the types of feelings that an alienated

individual experiences. These are such feelings as powerlessness, meaninglessness, normlessness, and estrangement.

With regard to political alienation, Marx identifies four factors that cause “alienation.” These are, according to Marx,

man’s relations to his product, his productive activity, other man, and the species.

In this paper, I intend to argue that Mother Courage, the main character of Brecht’s play, Mother Courage and Her

Children, fails to provide for her children financially because of a socio-psychological state defined by Marx as

“alienation”.ii My reading offers that Mother Courage’s attempt to maintain and secure financial profit leads to a tragic

failure because her endeavor falls into the Marxist category of alienated labor. Mother Courage pays a heavy price by

losing all her children for profit.

- Alienation: the Theoretical Background

In this paper, I intend to employ Marx’s theoretical propositions on an individual’s state of “alienation”. Primarily, the

concept of “alienation” applies to an individual’s sensual experience, where the loss of the sense of utility and the

inability to change one’s conditions are at stake. One instance of a person’s sensual experience under the influence of

“alienation” is when that person, in this case Mother Courage, is subject to irrational passions such as greed. Marx sees

greed both as one of the main characteristics of capitalists’ qualities and the motive of most capitalist actions.iii He

asserts that “greed is a function of alienation as a result of loss of ‘personal identity’ due to the effects of the division of

labor.”iv The sense of greed and the notion of consumption are directly related to each other. Erich Fromm argues that

the most striking kind of “alienation” is known as the process of consumption, which leads to dehumanization.v Mother

Courage is dehumanized in the process of sacrificing her children for profit.

IJCLTS 2 (4):30-39, 2014 31

Marx also theorizes mankind’s alienation in the political arena. He believes that under capitalism in a society, a worker

is compelled to sell his labor and his skills to the capitalist, and the worker himself controls neither the product of his

labor nor his labor itself. This leads to the laborer’s sense of “alienation”. Marx identifies four factors that cause

“alienation.” These are, according to Marx, man’s relations to his product, his productive activity, other man, and the

species.

First, with regard to man’s relation to his product, “alienation” is caused by the separation of the worker from the

product of his labor, where the worker has no control over the products he produces. Instead, products are controlled by

the capitalist.

Second is “alienation” in terms of the process of production, which is concerned with the fact that the work provides no

satisfaction but is only a source of physical exhaustion and mental debasement for the worker. Marx allocates a

particular place to man’s relationship to his activity. Thus the consciousness which man has of his activity is

transformed in a way that the species life becomes a means for him, and man’s consciousness is used to direct his

efforts for survival.

Third, the worker is alienated from other human beings due to the dissolution of human relationships and social bonds.

And finally, Marx makes the proposition that under capitalism man’s nature as a species is alienated in the sense that

mankind is alienated from the others.vi Moreover, Marx elaborates on the feeling of “estrangement” or “alienation”

which occurs due to social structures that deny human nature the chance to perform an activity in co-operation with

others.

Further, he lays great emphasis on the transformation of human labor itself into a commodity which is among the major

alienating forces in the capitalist world. Furthermore, the theory of “alienation” is employed by Marx to distinguish four

aspects of political “alienation” encompassing an individual’s experiencing lack of power, lack of meaning, the

lowering of norms, and estrangement.

This paper is divided into two sections. I have tried to unpack the elements of Marx’s theorizing of “alienation” to

include ideology, greed, physical and mental exhaustion, and loss of the sense of utility. I will attempt to show how

these are frequently strained in sociology by providing examples from Mother Courage. The first section, “alienation

and identity,” deals with the psychological effects of capitalism on Mother Courage and her attitude in a capitalist

society. This section treats “alienation” as a process which involves a crisis in identity and can lead to marginality. The

section also reflects on the process of consumption as an example of “alienation”, and greed as the motive of most

capitalist actions leading to “alienation”. The section, “alienation and political,” deals with the feelings of an individual

who does not feel to be a part of the political process. Moreover, the politically alienated believes that his social or

political actions make no difference. This section also introduces Marx’s notion of the four expressions of identification

that cause alienation. Marx categorizes these as man’s relation to his product, his productive activity, other man, and the

species. Finally the section negotiates how the four symptoms of alienation recognized by Marx as the symptoms of

political alienation appear in Mother Courage. These symptoms include the types of feelings which an alienated

individual experiences. These are such feelings as powerlessness, meaninglessness, normlessness, and estrangement. - Alienation and Identity

Mother Courage is alienated because she may lose her canteen to provide the ransom to rescue Swiss Cheese.

According to Weber, “alienation is the sensual experience of a subjective process of loss of sense of belonging and

utility in mankind’s own social environment when social ties are loosened. As a process it involves a crisis in identity

and can lead to marginality.”vii Hence, Mankind’s alienation is considered as one of the major psychological effects of

capitalism. Fromm claims: “Man does not experience himself as the active bearer of his powers, but as an impoverished

‘thing,’ dependent on powers outside of himself, unto whom he has projected his living substance.”viii It means that

alienation pervades the relationship of Mother Courage to her work, to the state and to herself. She establishes a way of

profit to provide a way for herself and her children’s consumption. This establishment of hers stands over and above

her. In the enclosed space where Mother Courage does business, she becomes a subject that dances to the tune of

capitalists. The capitalists, I mean those who hold power think about war as a way of maintaining control and

dominance over the bodies. The soldiers determine the war which brings order. At the beginning of the play, the

Sergeant says, war is “order” and the world is founded upon the order. In this sense, all the world’s resources are

dedicated to this order. In this context, the wealth of the village is seized by the rulers for their war, and does not remain

with its producers. By means of forced transfer of property with which the authorities gain while the little people lose,

the Sergeant shows what Mother Courage reveals in the third scene: “the rulers carry out war for obtaining one thing–

profit.” (iii. 204)

Brecht considers war as a crime. He considers Courage’s participation in war a crime.ix Mother Courage has an

incorrigible belief that she can profit from war. Her enthusiasm for war becomes more inhuman when we take into

account Brecht’s view that her business with war causes her children’s deaths. This picture of Courage as criminal is

supported by Brecht with examples of inhumanities that reveal her affinity with the crime in which she participates.

And each inhumanity is usually connected in some way with her business, which reinforces the idea that her business

with war is a crime. Courage is responsible for Swiss Cheese’s death when she hesitates to ransom him. The deaths of

her children may appear only further examples of the inhuman results of Courage’s involvement in war. As Brecht so

often tells us, the children’s deaths are the evidence that the little people cannot profit, but only lose from war. Mutter

Courage seems as a war for the rulers’ gain, which the little people like Mother Courage is motivated by a desperate

self-interest, even though she ultimately pays the price both in defeat and in victory. Nevertheless, Brecht posits a sort

of equivalence between war and capitalism, and by his own suggestion that the “business” of Mutter Courage

IJCLTS 2 (4):30-39, 2014 32

ultimately refers to capitalism. He describes capitalism as a social system that both gives a rise to war and needs war.

These statements show that Brecht’s portrayal of the Thirty Years War is a portrayal of capitalism.x

The portrayal of the war of the great against the small emphasizes the action of the great, that is, the fundamental

exercise of power by the rulers over the ruled which is known as exploitation. Throughout the play there are many

examples of the presence of exploitation in this capitalist society. As we have seen, the sergeant of scene one, when he

talks of carrying off the peasants’ goods, depicts no equitable exchange between producers, but instead a seizure or theft

of products in the name of the ruling class. Other representations of exploitation can be found in scene two we see that

the Swedish King taxes peasants in order to pay for his war; in scene three the army demolishes peasants’ crops– which

is no less an appropriation; in scene eight peasants are about to lose their home to war taxes; in scene twelve the army is

ready to induce compliance from the peasants by consuming– that is, slaughtering their livestock. In so doing, Brecht

alludes to exploitation when he declares to us that the little people do not gain from their rulers’ wars. That is, whatever

the outcome of war, neither worker nor soldier, as victims of exploitation, benefit from their labors in the interests of

their rulers. In the third scene when a soldier following orders tries to rescue the regimental cannon, Courage impresses

upon him how little he will gain by it. In other words, Mother Courage does not encourage heroic acts but dissuades the

masses from this virtue. Meanwhile, she tells the soldiers to abandon the regimental cannon, urges Swiss Cheese to

throw away the regimental cashbox. At the other occasion, Mother Courage warns Eilif that his heroic deeds

accomplish nothing except his death, just the same reveals in scene one that the glory of war is only death. While Eilif

is praised by his officer for his heroism, Courage only celebrates the foolhardiness of her son by slapping on his ears.

For Brecht capitalism is an inhuman and oppressive system in which a privileged group keeps the majority, I mean, the

workers, by means of force, economic compulsion, and ideological restraint in a deadly dependence on their exploiters.

Since the capitalists own the means to life. The capitalists, driven by profit, exploit the workers. By the same token,

Brecht elaborates that capitalism maintains itself through the ruin of labor, caused not only by exploitation, but also by a

labor process that alienates and dehumanizes the bodies. Hence, I refer not only to Brecht’s criticism of capitalism as an

inhuman, exploitative system but also to his view that capitalism is a warring society and so a cause of war. Brecht lays

great emphasis on their interdependence of war and capitalism. Brecht doubly curses Mother Courage. Not only does

Mother Courage support the crime of war due to her business which involves her in the war but also her view that she

can profit from the war of the powerful which results in perishing her children. Courage is an accomplice of war, her

part in the war is deliberate and persistent. In this respect, Brecht discusses that Courage must know the misery war

causes, its violence and starvation. She must know that war is a business waged by rulers for profit only. Courage must

know then that her attempt to identify with the rulers, her hope to profit as they do from war is doomed.xi

The authorities also find their benefits in the progression of war. In this respect, Mother Courage also as a capitalist

praises the continuation of war in order to gain more profit. In the sixth scene, there is a dialogue about the duration of

the war, with Mother Courage anxiously raising the question of how long war will last. If it is to continue, she can

comfortably invest in new goods for the cart. If it will finish soon, she cannot risk investing for fear of being left with

goods that cannot be sold. Then the Chaplain says that the war will continue:

Mother Courage: (Returning with Kattrin.) Don’t be silly, war’ll go on a bit longer, and we’ll make a bit more

money. That’s war for you. Nice way to get a living! (vi. 261-262)

Perhaps most striking kind of alienation is what Fromm has to mention about the process of consumption.

Brecht draws attention to the debasement of subjects through their ways of consumption. In capitalism, he says, the

masses are dehumanized. In Mutter Courage, Brecht refers to this dehumanization through his metaphor for the

reduction of a worker to a thing– commodity– in capitalism. Since everything in capitalism is calculated according to

profitability, Max Weber expresses that everything becomes reduced to a money value. Brecht says that the masses in

capitalism become crippled, and emptied of their content.xii Thus in a capitalistic society, by earning profit men acquire

things to consume; but such is our dehumanized state that it is we who are consumed.xiii That is, each time Mother

Courage leaves a child alone to make money she loses that child to the war in the quest for profit. The deaths of

Courage’s children are not only the result of their mother bringing them to war but also the act of Courage’s sacrifice of

her children to war, that is, to herself who consumes life in order to bring it forth again. And Courage’s absence on the

business that perpetuates the conditions which kill them is seen as part of the ritual of their sacrifice. She seems more

concerned with matters belonging to finance. In this sense Paul E. Farmer claims:

Brecht’s Mother Courage was a woman caught up in the economy of the war– selling food, and just about

anything in the mad optimistic belief that “war feeds its people better.” But war is a machine that devours its

young. Brecht wants to give a moral lesson that conducting business during a war leads to destitution

specifically for little people like Mother Courage.xiv

Given the choice between her child and profit– between protecting her children and business with war and death–

Courage chooses death. Her choice is echoed when Eilif is taken to his execution. When death as war exacts its final

payment from Eilif, Courage is again absent. At his moment of need when Eilif’s last wish is to see his mother, she is

away at town selling off her stock. Courage’s way of consumption results in the fact that she is never satisfied. She

seems worried about the prices that have fallen dramatically and pays no heed to the values like her son, Eilif. In the

eighth scene, she misses the opportunity to see Eilif for the last time because she gives priority to her profit than to her

son.

IJCLTS 2 (4):30-39, 2014 33

Mother Courage (to Yvette): Come along, got to get rid of my stuff afore prices start dropping… (Calls into

the cart.) Kattrin, church is off. I’m going to market instead. When Eilif turns up, one of you give him a drink.

(viii.228-232)

Mother Courage thus develops an ever-increasing need for more things, for more consumption. The constant increase of

needs forces her to an ever increasing effort and it makes her dependent on those needs and on the people on top and

institutions by whose help she attains them. At the beginning of the play, her attitude of excessive desire for wealth is

being revealed. She is obsessed with business and profit by taking a deadly risk to drive the cart right through the

bombardment to sell fifty loaves of bread. In a terrible place through bombardment she hopes to reap her reward.

Mother Courage as a sutler lives from war and feeds its engines. Just in case, she earns the epithet “hyena of the

battlefield.”

Mother Courage (to the Sergeant): Courage is the name they gave me because I was scared of going broke, so I

drove me cart right through bombardment of Riga with fifty loaves of bread. (i.72-73)

Her criminality destroys her children for the sake of her business. For, the hyena is already present with Courage’s first

appearance, in her business song. We have already seen the inhumanity revealed by this song, when Courage’s apparent

concern for the needs of the soldiers turns out to be a concern for them only while they remain customers, after which

she consigns them to the pit.

Mother Courage: Captains, how can you make them face it– marching to death without a brew?

Courage has rum with which to lace it and boil their souls and bodies through.

Their musket primed, their stomach hollow– Captains, your men don’t look so well.

So feed them up and let them follow while you command them into hell. (i.51-58)

The central issue of the effects of capitalism on personality is the phenomenon of alienation. The person does

not experience himself as the center of his world, as the creator of his own acts– but his acts and their consequences

become his masters whom he obeys.xv In the third scene while Swiss Cheese’ life is at risk, Mother Courage decides to

pawn the wagon and reclaim it with the money from the cash box. She ponders that she may get Swiss Cheese back.

Her delay results in the death of her son because she haggles for too long over the ransom. In this sense she is not the

center of her own acts, but her acts and their results become her master. The Sergeant brings the corpse for

identification if anyone knows him, but Mother Courage shakes her head to show that she does not know Swiss Cheese.

Sergeant: Here’s somebody we dunno the name of. It’s got to be listed, though, so everything’s shipshape. He

had a meal here. Have a look, see if you know him. (He removes the sheet.) Know him? (Mother Courage

shakes her head.) What never see him before he had that meal here? (Mother Courage shakes her head.)

(iii.670-675)

We can speak of alienation not only in relationship to other people, but also in relationship to oneself, when the

person is subject to irrational passions. The person who is given to the exclusive pursuit of his passion for money is

possessed by his striving for it. Courage’s inhumanity, I mean her passion for money, asserts itself when she bargains

for her son and wastes precious time trying to lower his price. In the end Courage agrees to the full amount, but it is too

late; her real choice was made when she first refused to sell the wagon and so reduced her son’s value. In the play,

Mother Courage eventually loses control of the situation and is unable to resolve her financial-family dilemma. She

strives for keeping money for herself as much as she can. She says:

Mother Courage: How’m I to payback two-hundred then? I just need a moment to think, it’s bit sudden,

what’m I to do, two hundred’s too much for me. (iii. 650-652)

Thus, Marx observes greed as one of the main characteristics of capitalists’ qualities. In Marx, greed is the motive of

most capitalist actions.xvi The sense of greed is concrete when Mother Courage refuses to give a soldier a drink because

he cannot pay. Her refusal highlights her sense of greed as a capitalist and her thirst for financial gain.

Mother Courage says: Can’t pay that it? No money, no schnapps (v.4).

Brecht utters that “Mother Courage is a profiteer who sacrifices her children to her commercial interests and cannot

learn from her experience.”xvii She declares that war is a good provider by confessing “war gives its people a better deal

(viii. 346).” Peter Demetz writes: “Brecht tried to point out Mother Courage’s greed and her commercial participation in

the murderous war.”xviii Her greed is concrete when she haggles over the bribe needed to free the captured Swiss

Cheese, and the delay results in the execution of her son. Since she cannot make any changes, she is defined as

alienated. Indeed her greed leads her to alienation. Pursuant to Marxist teachings, “Man has to be made aware of his

state of alienation in order to be able to change his conditions.”xix Nevertheless, her unawareness is reflected when she

predicts that the death will come to each of her children.

Mother Courage: (taking out a sheet of parchment and tearing it up). Eilif, Swiss Cheese, Kattrin, may all of us

be torn apart like this if we let ourselves get too mixed up in the war! Watch! Black is for death, so I’m putting

a big black cross on this slip of paper. (i.215-218)

The Sergeant and each of her children draw lots to see what awaits them in war, they all draw death. It is true that

Courage prearranges this result, to distract the soldiers from recruiting her sons and to dissuade her children from

getting too close to war. Yet the fraud is true. Mother Courage mentions the same fact elsewhere. She compares the

recruiter’s invitation to her son with the “angler’s to the worm; getting to close to war, she says, is like lambs going to

IJCLTS 2 (4):30-39, 2014 34

slaughter (i.182);” a song which she seems to have taught her son tells us that a soldier’s only reward is death; she does

not call the soldiers’ march into battle a road to glory, instead “she calls it a march into the maw of hell (iii.99-101).”

In relation to the discussion about individual alienation, I think of alienation as process which involves a crisis in

identity and can lead to marginality. It functions as a devastating effect of capitalistic production on human beings,

basically on their social processes of which they are a part. Now, it seems appropriate to begin with the topic of political

alienation which has direct effect on the identity of the self in the political and social processes. Marx develops a theory

of how human beings are shaped by the society they lived in, and how they can act to change that society. I propose that

alienation is the state of being segregated from one’s community. So, this type of alienation may lead to lack of

engagement in the political system. In this respect, political alienation has relevance with individual alienation since the

subject is no longer identifying with any particular political party, and may result in abstention and apathy towards

political process. - Alienation and Politics

Political alienation comes to function as a term signifying almost any form of ‘unhappiness’ about politics or

dissatisfaction with some aspect of society. In this sense, a politically alienated subject is also isolated in the social

system. “Alienation” shows how mankind sinks to the level of a commodity, and indeed the most wretched of all

commodities, since the harder he labors and the more he produces the more miserable he becomes. From this premise,

the more mankind exerts himself the more powerful becomes the world of things which he creates and which confront

him as alien objects. The greater the mankind’s activity, the more pointless his life becomes.

The theory of alienation is the intellectual construct in which Marx displays the devastating effect of capitalist

production on human beings, on their physical and mental states, and on their social processes of which they are a part.

Marx claims that one of the manifestations of alienation is that “all is under the sway of inhuman power.” It means that

in capitalist society, the power of capital reflects the power of the alien force which rules the powerless subjects. Thus,

capitalism is an exploitative system that causes and requires war. In a text from Couragemodell Brecht suggests that the

‘business’ of Mother Courage and capitalism are the same. In Brecht’s terms:

The war is the business of the big men who manipulate politics for their own advantage, exploiting mankind,

making man’s relationship with man primarily a business relationship.xx

In so doing, Mother Courage as an alienated has no chance to compete with the authorities. Not only does the alienated

subject, Mother Courage sell her power to the master of capital but also the ‘sway of inhuman power’ threatens the

livelihood of her and her children. In capitalism, the alienated subjects are dehumanized. This dehumanization refers to

the reduction of the subject to a thing or in Marxian term, commodity because everything in capitalism is calculated

according to profitability. Now it seems appropriate to point to Courage’s inhuman unconcern for the slaughtered

peasants, and to her business interests as far as her children’s labor and Swiss Cheese’s ransom are concerned. Mother

Courage is only motivated by profit. In the scene nine, her decision to remain with Kattrin is not only motivated by

maternal love, but also by a hope for profit in war:

The Cook: Last word. Think it over.

Mother Courage: I’ve nowt to think. I’m not leaving her here. (ix. 162-163)

Being aware of the privations suffered in war, the Cook decides to offer a partnership to Courage. Utrecht seems to

stand outside the turmoil of war. Certainly Courage understands it as an escape from war. But Courage rejects Utrecht

because her favor of war. As a merchant, she depends upon war for her profit.

According to Marx, “alienation as the product of capitalism refers to the situation of modern man, deprived of, robbed

of, or alienated from the totality of human nature which should be his.”xxi He believes that under capitalism in a society,

a worker is compelled to sell his strength and his skills to the capitalist. The play unfolds Mother Courage as a victim of

the capitalist way of life, in which war is a way of doing business. Even after losing all her children, she still attempts to

carry on with her business. The play, Mother Courage, attempts to show how capitalism brutalizes Mother Courage

herself. Her business with war causes her children’s deaths. Inhumanity is revealed in her affinity with participation in

the war. The play gives a picture of Courage’s inhumanity which is integral to her business. I mean, Courage’s business

is bound up with the misery of others. In fact, the idea that one’s happiness is purchased at the price of the unhappiness

of another is clearly part of Courage’s thinking. In a capitalist society because mankind’s ability is calculated according

to his or her amount of profit, so everyone becomes a competitor. Individuals become isolated monads, concerned only

for themselves and without regard for others. All these following examples reveal the fact that Courage shows that her

desire for profit knows no compassion. In the play, Mother Courage’s business is mingled with the misery of others.

Her preference for war over peace, death over life, extends even to her own children. In scene two, Courage exploits the

general starvation at the siege of Walhoff to extort from the cook an inflated price for her capon:

The Cook: Sixty hellers for a miserable bird like that?

Mother Courage: Miserable bird? This fat brute? Mean to say some greedy old general– and watch your step if

you got nowt for his dinner– can’t afford sixty hellers for him?

… Mother Courage: What, a capon like this you can get just down the road?

… A rat you might get…. Fifty hellers for a giant capon in time of siege! (ii. 1-4, 6-7, 11-12)

IJCLTS 2 (4):30-39, 2014 35

At the end of the second scene, those who live in Halle know that the town is in danger and so they try to sell off their

possessions before they flee. Courage exploits their fear and desperation to purchase the goods cheaply. Courage tries to

profit from the misfortune of others. When Courage wants to mortgage her wagon for her son’s life, she preys on the

fears of Yvette, the camp prostitute. Yvette attempts to hide her fear by checking her cart or counting the shirts:

Mother Courage: Yvette, it’s no time for checking your cart…. You promised you’d talk to sergeant about

Swiss Cheese, there ain’t a minute to lose….

Yvette: Just let me count the shirts.

Mother Courage: (Pulling her down by the skirt.)… For God’s sake, pretend it’s your friend. (iii. 573-575,

577-578, 580)

Hence, Marx identifies four expressions of identification that cause alienation. These are man’s relations to his product,

his productive activity, other man and the species.xxii By the same token, these propositions mentioned by Marx have

relevance to the position of Mother Courage as an alienated woman. Mother Courage’s alienation is the result of

following factors.

In his essay 1814, Marx discusses that under the system of capitalism the worker is alienated from the product of his

labor and from the means of production– both of which has become things not belonging to him.xxiii Thus the worker

separated from his work and from his product, is alienated from himself since his labor is no longer his own but the

property of another. In so doing, by man’s relations to his product, I mean Courage’s activity mortifies her soul and

devours her children, in the sense that Mother Courage’s canteen exercises power over her, and makes her dependent

and vulnerable. It appears true that Mother Courage at first intends to sell her canteen to ransom Swiss Cheese’s life.

But later on, not only does she mean to sell the canteen but also to mortgage it. She is dependent on the function of her

canteen, because her state of business may go at risk by losing it. That is, Courage intends to utilize Yvette’s money to

rescue Swiss Cheese and then to use the money from the cashbox to recover her wagon. At any rate, she does not want

to lose her canteen. It seems more valuable than her son’s life. While at the end of the play she takes up and hauls the

damaged canteen which is almost empty. I think this image of emptiness of canteen reflects her state of alienation.

By man’s relation to his productive activity, it fosters the impression of Mother Courage who has been exploited due to

‘the means of production.’xxiv Because, capitalism maintains the means of production through the ruin of labor by a

labor process that dehumanizes and alienates Mother Courage. Throughout the play, she does not extract surplus labor

because she is considered as a poor candidate to represent her business in the capitalist system. That is, she is in danger

of being impoverished because of the smallness of her capital.xxv To put it differently, the capitalists steal the subject’s

labor to reap the profits. While, we see that little people like Courage is forced to accommodate because of the danger

and deprivation she may endure in such a disordered ruled land.

Mankind is alienated from other men because his chief link with them is the commodities they exchange or produce.

The transformation of human labor into a commodity is among the major alienating forces in the capitalist world. By

alienation to other man, I intend to say that Mother Courage is isolated from other human beings and feels indifferent to

others. It connotes to an individual feeling or state of dissociation from self, and from others. F.H. Heinemann suggests

that alienation objectively refers to different kinds of dissociation, break or rupture between human beings and their

surroundings.xxvi For instance, when the Chaplain needs some linen to bandage some peasants whose farmhouse has

been demolished, Mother Courage’s daughter Kattrin wants to provide him with some shirts from the wagon, but

Mother Courage refuses to give up those clothes, declaring that the peasants are unable to purchase. At last, The

Chaplain forcefully takes four of her officer’s shirts, tearing them into strips to use as bandages:

Mother Courage: I got none. All my bandages were sold to regiment. I ain’t tearing up my officer’s shirts for

that lot.

The Chaplain: I need linen, I tell you.

Mother Courage: (Blocking Kattrin’s way into the cart by sitting on the step.) I’m giving nowt. They’ll never

pay, and why, nowt to pay with. (v.11-16)

Lastly, in treating species alienation, Marx gives a favored place to man’s relation to his activity. For Marx, species is

the category of those potentialities which mark man off from other living creatures.xxvii Necessarily, mankind is

restricted in his or her use of objects to what their owners will allow, which is less than his or her powers require. In

species alienation, ‘activity’ is the chief means through which the individual expresses and develops his powers, and is

distinguished from other’s activity by its range, adaptability, skill and intensity.

xxviii Courage as a capitalist has

something in common with the rulers which admits her higher state of position in comparison to the other little people.

She oppresses and exploits others. For example, we have seen that she converts her children into draft animals to pull

the canteen. I mean, her children contribute their labor to Courage’s work, much as the soldiers contribute their labor to

the project of their rulers. But In capitalism, however, the worker’s labor “turns for him the life of the species into a

means of individual life”.xxix Work has become a means to stay alive rather than life being an opportunity to do work. It

asserts that man’s existence has become the purpose of work. In the play, Courage’s aim is used to direct her efforts at

staying alive, if she wants to be successful in her business. In the third scene, Mother Courage and Swiss Cheese ignore

knowing each other. Although, Courage loses her son but she saves her life to continue her business and also her

daughter, Kattrin.

IJCLTS 2 (4):30-39, 2014 36

Political alienation is the feeling of an individual that he is not a part of the political process. The politically alienated

believes that his social or political actions make no difference. Marx discusses the types of feelings which are the

symptoms of alienation. These are powerlessness or a feeling that one cannot influence the social situations in which

one interacts. Further, there is meaninglessness or a belief that an individual has no guide for conduct. The next is

normlessness or an individual’s feeling that illegitimate means are required to achieve important goals. And lastly, there

is estrangement or a feeling that one cannot find self rewarding activities in life.xxx

Modern conditions of work under capitalism are alienating largely because the individual worker loses– or is unable to

gain– control over his social machines.xxxi Firstly, political powerlessness is the feeling of an individual that his political

action has no influence in determining the course of events. Those who feel politically powerless do not believe that any

action they may perform can determine the outcome they desire. This feeling of powerlessness arises from and

contributes to the belief that the community is not controlled by the mass, but rather by a small number of powerful and

influential person who are in charge to control.xxxii In the play it denotes that the rulers pay no heed to peasant’s

deficiencies so that to change their conditions. Courage’s state of powerlessness reveals in another scene when she

appears outside an officer’s tent, complaining to a Clerk that the army has destroyed her merchandise and charged her

with an illicit fine. She plans to file a complaint with the captain. The Clerk responds that she ought to be grateful the

soldiers let her stay in business:

The Clerk (to Mother Courage): Better shut up. We’re short of canteen, so we let you go on trading (iv. 9-10).

Mother Courage’s state of powerlessness is revealed again within the play. James K. Lyon in his “Brecht Unbound”

declares that Brecht’s Marxist views caused him to look at Mother Courage as an alienated and powerless woman.xxxiii

Mother Courage is manifested as powerless in the sense that she cannot make any difference. She becomes astonished

to hear her son’s voice again, but she is powerless to take Eilif away from The General. Mother Courage says:

Mother Courage: My eldest boy Eilif. It’s two years, since I lost sight of him. They (the soldiers) pinched him

from me on the road (ii.64-65).

Workers are dehumanized not only by the work situation but also by the ends for which our society uses work, chiefly

consumption for its own sake. A condition that leads to isolation resulting from capitalism that makes the individual

even more lonely and alienated; while, intensifying his feelings of insignificance and powerlessness.xxxiv In this respect,

Mother Courage feels powerless and insignificant due to her state of alienation. In the first scene, Courage is powerless

because her actions have no influence or control over the events. For example, she is unable to stop the army from

taking her sons Eilif and Swiss Cheese away. She is desperate in the face of the political conditions surrounding her and

her children.

The state of political meaninglessness is revealed when political decisions seem unpredictable through Courage’s

perception. Mother Courage has a kind of perception of war that she may both reap the profit and nourish her children.

She does not think that her participation results in perishing her children. She does not understand the deep meaning of

the Sergeant’s comment: “Like the war to nourish you? Have to feed it something too (i.332-333).” She prophesies truly

that those who come to war will be perished. She warns that getting too close to war means destruction. Nevertheless,

she keeps on doing business. For at the end, just as she did after losing Eilif to the army, after losing Swiss Cheese to

the firing squad, and after losing Kattrin to the Imperialists, she continues her struggle; though her business is a mere

shadow of its former self, though she is surrounded by the devastation of a war seemingly without end. She does not

have such a perception that she will lose all her children under the inhuman system of the ruler which exploits Courage

by raising her children to be its sacrifices.

Not only does Courage have no guide for conduct, but also she makes criticism of bad leadership. The feeling of

meaninglessness is tangible when in scene four a young soldier complains of hunger. Courage points out that his

suffering is a result of bad leadership. She implies that hunger becomes great. Courage’s criticism of the rulers, her

exposure of them as the cause of the little people’s suffering is bold, but her truly dangerous aspect appears when she

suggests that no improvement will come from those in power:

Young Soldier: He’s (The general) whoring away my reward and I’m hungry. I’ll do him.

Mother Courage: Oh I see, you’re hungry. Last year that general of yours ordered you all off roads and across

fields so corn should be trampled flat; I could’ve got ten florins for a pair of boots s’pose anyone’d been able

to pay ten florins. Thought he’d be well away from that area this year, he did, but here he is, still there, and

hunger is great. I see what you are angry about (iv.46-54).

Feelings of political alienation may also be experienced in the sense of the lowering of an individual’s political ethics or

what is called as normlessness. This occurs when standards of political behavior are violated in order to achieve some

goal. This is likely to occur when the political structure prevents the attainment of political objectives through

institutionally prescribed means.xxxv Normlessness is defined as no longer the lack of identified viable social norms, but

the result of circumstances relating to the “complexity and conflict in which individuals become unclear about the

composition and enforcement of social norms. Sudden and abrupt changes occur in life conditions, and the norms that

usually operate may no longer seem adequate as guidelines for conduct.”xxxvi Courage points out that the rulers– among

whom she includes the popes– do not carry out this war for the faith, but for profit. In scene eight, when the Chaplain

rebukes Courage as a hyena of the battlefield who lives from war, Courage mentions that he too lives from her

business– and so from war (which the Chaplain is considered as the rulers’ ideologue, because he is a pope). When she

bargains for Swiss Cheese’s life she barks at the chaplain who remains silent. So the Chaplain, whose function as a pope

IJCLTS 2 (4):30-39, 2014 37

must be to conduct the behaviors of individuals, seems unsuitable as a guideline for conduct. Courage declares that

religious leaders are among those whom are bad for the health of the little people. In the third scene, she dismisses

Yvette to make the deal with the generals and save her son, Swiss Cheese, while the Chaplain haggles on the amount of

the money:

The Chaplain: It doesn’t have to be the whole two hundred either, I’d go up to a hundred and fifty, that may be

enough.

Mother Courage: Since when has it been your money? You kindly keep out of this. You’ll get your hotpot all

right, don’t worry. Hurry up and don’t haggle, it’s life or death. (Pushes Yvette off.) (iii.584-589)

Marx considers estrangement to be the end result and thus the heart of political alienation.xxxvii From personal

alienation’s perspective: alienated individual may feel disconnected from himself. In such cases, Mankind may not be

able to find activities that are interesting to him. In the play despite Courage’s endurance to gain profit from the war, it

seems that she is not happy with her business anymore. I can say that Courage not only affirms her world but also

negates or criticizes it. This is because the restraints and restrictions imposed by the authority. The elements of

Courage’s revolt represent the oppressed of patriarchal capitalism that is– the women like Mother Courage herself, and

the little people. Her feminist rebellion opposes a patriarchy, a system of violence and domination that would rob

Courage of both her freedom and her goods. She is represented as an oppressed woman pressed hard by the patriarchal

society. Church, religion, and paternity are determined as the patriarchal authority. In doing so, her rebellions all imply

an attack on authority to offer freedom instead of renunciation. In scene four, I think the subversive message of Courage

is embedded in the song of the Grand Capitulation.xxxviii

From political alienation’s perspective: estrangement from political activity refers to an individual’s rejection of the

political system. Mutter Courage fosters the impression of a division into two opposed groups, the great and the small,

the powerful and the powerless; with the great represented here by the military, and the little people by the peasants

(supplemented by the soldiers and Courage’s family.) she finds that the rulers do not carry out this war for the faith, but

for profit. The rulers maintain a hold over the little people. Mother Courage believes that it is the little people who

suffer in the war. In this sense, authority is right to perceive a threat in Courage, since she exposes the true purposes of

the rulers to the little people. Courage rejects the political system which takes the bodies’ health at risk to reap the profit

for itself. Put it more succinctly, Courage dismisses the justice of authority that the little people instead of waiting for

political system which restrains them to whether give them satisfaction or not, should take their fate into their own

hands.xxxix

- Conclusion

This paper has tried to analyze the main character of the play, Mother Courage, under the devastating effects of

alienation as the capitalist production both in ‘alienation and identity’ which deals with the sensual experience of a

subjective process of loss of sense of belonging and utility in mankind’s own social environment as a consequence of

living in a capitalist society, and in a larger zone, ‘alienation and political,’ mankind sinks to the level of a wretched

commodity, since the harder Courage labors and the more she produces the more miserable she becomes. From

‘personal alienation,’ she does not experience herself as the active bearer of her power, but as an impoverished

commodity. She maintains a way of profit to provide a way for herself and her children’s consumption. Courage’s way

of consumption results in the fact that she is never satisfied. Her belief in war so that she can get a share as much as the

rulers, becomes more inhuman when her business with war causes her children’s deaths and her exploitation. Her

exploitation drives from her dependence on rulers by whose help she attains more consumption. From ‘political

alienation,’ Mother Courage is shown as a politically alienated since the harder she works throughout the play to earn

money, the more miserable and wretched she becomes in the end. She is politically alienated and has no chance to

compete with the authorities. Courage sells her power to the master of capital which threatens the livelihood of her and

her children. Capitalism brutalizes Mother Courage herself and even makes her greedy to gain profit for more

consumptions. As a result, she loses all her children in the quest of her profit.

References

Arthur. G. N., Sara F. C. (2000). Intimacy and alienation: Forms of estrangement in female/male relationships, New

York: Garland Publishing.

Blau, H. (1957). “Brecht’s Mother Courage: The Rite of War and the Rhythm of Epic.” Educational Theatre Journal: 1-

Bloom, H. (2002). Berthold Brecht, London: Chelsea House Publishers.

Brecht, B. (1980). Mother Courage and Her Children. Trans. John Willet. London: Penguin Classics Edition.

—. (1978). Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic, ed. and trans. John Willett, London: Methuen.

Churchich, N. (1990). Marxism and Alienation. London: Associated UP.

Constantinidis, S. E. (2008). Text & Presentation, London: McFarland & Company.

Esslin, M. (1969). Bertolt Brecht. New York: Columbia UP.

—. (1984). Brecht, A Choice of Evils: A Critical Study of the Man, His Work and His Opinions. 4, London: Methuen.

Farmer, P. E. (2008). “Mother Courage and the Future of the War, Social Analysis,” ProQuest Central: 166-178.

Fromm, E. (1961). Marx’s Concept of Man, New York: Frederick Ungar.

Gray, R. (1961). Brecht, Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd.

IJCLTS 2 (4):30-39, 2014 38

Hier, S. P. (2005). Contemporary Sociological Thought: Themes and Theories, Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press.

Leach, R. (1994). Mother Courage and her Children: The Cambridge Companion to Brecht, Eds. Peter Thomson, and

Glendye Sacks, Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

Levin L., M. (I960). The Alienated Voter, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Lucacs, G. (1983). History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics. Trans. Rodney Livingstone,

Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Martin, C., Bial, H. (2000). Brecht Sourcebook, New York: Routledge.

Marx, K., Engels, F. (1988). Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, New York: Prometheus Books.

Mumford, M. (2009). Bertolt Brecht, London: Routledge.

Ollman, B. (1996). Alienation: Marx’s conception of man in capitalist society, 2, New York: Cambridge UP.

Richard Jones, D. (1986). Great Directors at Work: Stanislavsky, Brecht, Kazan, Brook, Berkeley: University of

California Press.

Styan, J. L. (1981). Modern Drama in Theory and Practice: Expressionism and Epic Theatre, Cambridge: Cambridge

UP.

Subberwal, R. (2009). Dictionary of Sociology, Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill.

Taylor, Ch. (1958). “Alienation and Community,” Universities and Left Review, London.

Tedman, G. (1988). Aesthetics & Alienation, London: Zero books.

Thomson, P. (1997). Brecht: Mother Courage and Her Children, London: Cambridge UP.

Thomson, P., sack, G. (1994). The Cambridge Companion to Brecht, Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

Willett, J. (1967). The Theatre of Bertolt Brecht: A Study from Eight Aspects. 3. London: Methuen.

—. (1983). Brecht in Context: Comparative Approaches. London: Methuen.

Williams, R. (1976). Drama from Ibsen to Brecht, Harmondsworth: Penquin.

Zander, V. (2004). Identity and marginality, Berlin: Die Deutsche biblothek.

Notes

i

Charles Taylor, “Alienation and Community,” Universities and Left Review (London, 1958) 19.

ii

Brecht, B. (1980). Mother Courage and Her Children. Trans. John Willet. London: Penguin Classics Edition. All the

citations are from the same text.

iii Bertell Ollman, Alienation: Marx’s conception of man in capitalist society, 2nd edition, (New York: Cambridge UP,

1996) 155.

iv

Gary Tedman, Aesthetics & Alienation, (London: Zero books, 1988) 97.

v

Erich Fromm. Marx’s Concept of Man, (New York: Frederick Ungar, 1961) 73.

vi

For more discussion, see also Ranjana Subberwal, Dictionary of Sociology, (Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill, 2009) 9-12.

vii

Viktor Zander, Identity and marginality, (Berlin: Die Deutsche biblothek, 2004) 24.

viii

Viktor Zander, 26.

ix

Bertolt, Brecht. Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic, ed. and trans. John Willett, (New York: Hill

and Wang; London: Methuen, 1978) 109.

x

Peter Thomson. Brecht: Mother Courage and Her Children, (London: Cambridge UP, 1997) 37.

xi

Carol Martin, Henry Bial. Brecht Sourcebook, (New York: Routledge, 2000) 51.

xii

John Willett. Brecht in Context: Comparative Approaches, (London: Methuen, 1983) 74.

xiii Erich Fromm. Marx’s Concept of Man, 74.

xiv

Paul E. Farmer, Mother Courage and the future of war, Proquest Central, 2008, 178.

xv Erich Fromm. Marx’s Concept of Man, 56.

xvi

Bertell Ollman, Alienation: Marx’s conception of man in capitalist society, 2nd edition, (New York: Cambridge UP,

1996) 155.

xvii

David Richard Jones, Great Directors at work (London: University of California Press, 1986) 120.

xviii

Stratos E. Constantinidis, Text & Presentation, (London: McFarland & Company, 2008) 187.

xix

Stratos E. Constantinidis, 185.

xx

Harold Bloom. Berthold Brecht, (London: Chelsea House Publishers, 2002) 39.

xxi

Ronald Gray. Brecht, (Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd, 1961) 43.

xxii

Ranjana Subberwal, 12.

xxiii

Nicholas Churchich. Marxism and Alienation, (London: Associated university presses, 1990) 83.

xxiv Martin Esslin. Bertolt Brecht, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1969) 39. See also Brecht, A Choice of Evils:

A Critical Study of the Man, His Work and His Opinions, 4th revised, ed. (London: Methuen, 1984) 57.

xxv Herbert Blau, “Brecht’s Mother Courage: The Rite of War and the Rhythm of Epic” Educational Theatre Journal. 9

(1957): 1-10. See also Robert Leach, “Mother Courage and her Children: The Cambridge Companion to Brecht,” eds.

Peter Thomson, and Glendyr Sacks. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994) 128-138.

xxvi

Georg Lucacs, History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics. Trans. Rodney Livingstone,

(Cambridge: The MIT Press. 1983) 128.

xxvii

Karl Marx, Frederick Engels, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, (New York: Prometheus Books,

1988) 75.

xxviii

Karl Marx, Frederick Engels. 77.

IJCLTS 2 (4):30-39, 2014 39

xxix Meg Mumford, Bertolt Brecht, (London: Routledge, 2009) 68.

xxx

Rajana Subberwal, 12.

xxxi

Sean P. Hier, Contemporary Sociological Thought: Themes and Theories, 71.

xxxii Murray L. Levin, The Alienated Voter, (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, I960) 65.

xxxiii John Willett. The Theatre of Bertolt Brecht: A Study from Eight Aspects, 3rd ed. (London: Methuen, 1967) 134. See

also J. L. Styan. Modern Drama in Theory and Practice: Volume 3, Expressionism and Epic Theatre.

xxxiv Erich Fromm. Marx’s Concept of Man, 68.

xxxv

Levin L. Murray. 67.

xxxvi Neal, Arthur. G. and Collas, F. Sara, Intimacy and alienation: Forms of estrangement in female/male relationships,

(New York: Garland Publishing, 2000) 122.

xxxvii

Raymond Williams, Drama from Ibsen to Brecht, (Harmondsworth: Penquin, 1976) 52.

xxxviii

Peter Thomson, Glendyr sack. The Cambridge Companion to Brecht, (Cambridge: Cambridge UP) 1994,135.

xxxix John Willett. The Theatre of Bertolt Brecht, 89. See also Willett, John. Brecht in Context: Comparative

Approaches, (London: Methuen, 1983) 65.

Mother Courage and Her Children

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: “Mother Courage and Her Children” – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

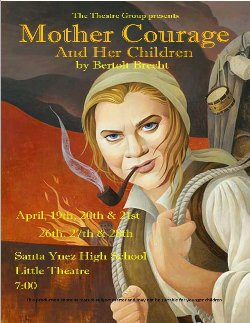

Mother Courage and Her Children (German: Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder) is a play written in 1939 by the German dramatist and poet Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956), with significant contributions from Margarete Steffin.[1] Four theatrical productions were produced in Switzerland and Germany from 1941 to 1952, the last three supervised and/or directed by Brecht, who had returned to East Germany from the United States.

Several years after Brecht’s death in 1956, the play was adapted as a German film, Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder (1961), starring Helene Weigel, Brecht’s widow and a leading actress.

Mother Courage is considered by some to be the greatest play of the 20th century, and perhaps also the greatest anti-war play of all time.[2] Critic Brett D. Johnson points out, “Although numerous theatrical artists and scholars may share artistic director Oskar Eustis’s opinion that Brecht’s masterpiece is the greatest play of the twentieth century, productions of Mother Courage remain a rarity in contemporary American theatre.”[3]

Synopsis[edit]

The play is set in the 17th century in Europe during the Thirty Years’ War. The Recruiting Officer and Sergeant are introduced, both complaining about the difficulty of recruiting soldiers to the war. Anna Fierling (Mother Courage) enters pulling a cart containing provisions for sale to soldiers, and introduces her children Eilif, Kattrin, and Schweizerkas (“Swiss Cheese”). The sergeant negotiates a deal with Mother Courage while Eilif is conscripted by the Recruiting Officer.

Two years thereafter, Mother Courage argues with a Protestant General’s cook over a capon, and Eilif is congratulated by the General for killing peasants and slaughtering their cattle. Eilif and his mother sing “The Fishwife and the Soldier”. Mother Courage scolds her son for endangering himself.

Three years later, Swiss Cheese works as an army paymaster. The camp prostitute, Yvette Pottier, sings “The Fraternization Song”. Mother Courage uses this song to warn Kattrin against involving herself with soldiers. Before the Catholic troops arrive, the Cook and Chaplain bring a message from Eilif. Swiss Cheese hides the regiment’s paybox from invading soldiers, and Mother Courage and companions change their insignia from Protestant to Catholic. Swiss Cheese is captured and tortured by the Catholics, having hidden the paybox by the river. Mother Courage attempts bribery to free him, planning to pawn the wagon first and redeem it with the regiment money. When Swiss Cheese claims that he has thrown the box in the river, Mother Courage backtracks on the price, and Swiss Cheese is killed. Fearing to be shot as an accomplice, Mother Courage does not acknowledge his body, and it is discarded.

Later, Mother Courage waits outside the General’s tent to register a complaint and sings the “Song of Great Capitulation” to a young soldier anxious to complain of inadequate pay. The song persuades both to withdraw their complaints.

Mother Courage grows desperate to protect her business, so much so that she refuses to give fabric to treat wounded civilians. The Chaplain takes her supplies anyway.

When Catholic General Tilly’s funeral approaches, the Chaplain tells Mother Courage that the war will still continue, and she is persuaded to pile up stocks. The Chaplain then suggests to Mother Courage that she marry him, but she rejects his proposal. Mother Courage curses the war because she finds Kattrin disfigured after being raped by a drunken soldier. Thereafter Mother Courage is again following the Protestant army.

While two peasants are trying to sell merchandise to her, they hear news of peace with the death of the Swedish king. The Cook appears and causes an argument between Mother Courage and the Chaplain. Mother Courage is off to the market while Eilif enters, dragged in by soldiers. Eilif is executed for killing a peasant while stealing livestock, trying to repeat the same act for which he was praised as hero in wartime, but Mother Courage never hears thereof. When she finds out the war continues, the Cook and Mother Courage move on with the wagon.

In the seventeenth year of the war, there is no food and no supplies. The Cook inherits an inn in Utrecht and suggests to Mother Courage that she operate it with him – but he refuses to harbour Kattrin because he fears that her disfigurement will repel potential customers. Thereafter Mother Courage and Kattrin pull the wagon by themselves.

When Mother Courage is trading in the Protestant city of Halle, Kattrin is left with a peasant family in the countryside overnight. As Catholic soldiers force the peasants to guide the army to the city for a sneak attack, Kattrin fetches a drum from the cart and beats it, waking the townspeople, but is herself shot. Early in the morning, Mother Courage sings a lullaby to her daughter’s corpse, has the peasants bury it, and hitches herself to the cart.

Context[edit]

Mother Courage is one of nine plays that Brecht wrote in resistance to the rise of Fascism and Nazism. In response to the invasion of Poland by the German armies of Adolf Hitler in 1939, Brecht wrote Mother Courage in what writers call a “white heat”—in a little over a month.[4] As the preface to the Ralph Manheim/John Willett Collected Plays puts it:

Mother Courage, with its theme of the devastating effects of a European war and the blindness of anyone hoping to profit by it, is said to have been written in a month; judging by the almost complete absence of drafts or any other evidence of preliminary studies, it must have been an exceptionally direct piece of inspiration.[5]

Following Brecht’s own principles for political drama, the play is not set in modern times but during the Thirty Years’ War of 1618–1648, which involved all the German states, France and Sweden. It follows the fortunes of Anna Fierling, nicknamed Mother Courage, a wily canteen woman with the Swedish Army, who is determined to make her living from the war. Over the course of the play, she loses all three of her children, Schweizerkas, Eilif, and Kattrin, to the very war from which she tried to profit.

Overview[edit]

The name of the central character, Mother Courage, is drawn from the picaresque writings of the 17th-century German writer Grimmelshausen. His central character in the early short novel, The Runagate Courage,[6] also struggles and connives her way through the Thirty Years’ War in Germany and Poland. Otherwise the story is mostly Brecht’s, in collaboration with Steffin.

The action of the play takes place over the course of 12 years (1624 to 1636), represented in 12 scenes. Some give a sense of Courage’s career, but do not provide time for viewers to develop sentimental feelings and empathize with any of the characters. Meanwhile, Mother Courage is not depicted as a noble character. The Brechtian epic theatre distinguished itself from the ancient Greek tragedies, in which the heroes are far above the average. Neither does Brecht’s ending of his play inspire any desire to imitate the main character, Mother Courage.

Mother Courage is among Brecht’s most famous plays. Some directors consider it to be the greatest play of the 20th century.[7] Brecht expresses the dreadfulness of war and the idea that virtues are not rewarded in corrupt times. He used an epic structure to force the audience to focus on the issues rather than getting involved with the characters and their emotions. Epic plays are a distinct genre typical of Brecht. Some critics believe that he created the form.[8]

As epic theatre[edit]

Mother Courage is an example of Brecht’s concepts of epic theatre and Verfremdungseffekt, or “V” effect; preferably “alienation” or “estrangement effect” Verfremdungseffekt is achieved through the use of placards which reveal the events of each scene, juxtaposition, actors changing characters and costume on stage, the use of narration, simple props and scenery. For instance, a single tree would be used to convey a whole forest, and the stage is usually flooded with bright white light, whether it’s a winter’s night or a summer’s day. Several songs, interspersed throughout the play, are used to underscore the themes of the play. They also require the audience to think about what the playwright is saying.

Roles[edit]

- Mother Courage (also known as “Canteen Anna”)

- Kattrin (Catherine), her mute daughter

- Eilif, her older son

- Schweizerkas (“Swiss Cheese”, also mentioned as Feyos), her younger son

- Recruiting Officer

- Sergeant

- Cook

- Swedish Commander

- Chaplain

- Ordinance Officer

- Yvette Pottier

- Man with the Bandage

- Another Sergeant

- Old Colonel

- Clerk

- Young Soldier

- Older Soldier

- Peasant

- Peasant Woman

- Young Man

- Old Woman

- Another Peasant

- Another Peasant Woman

- Young Peasant

- Lieutenant

- Voice

Performances[edit]

The play was originally produced at the Schauspielhaus Zürich, produced by Leopold Lindtberg in 1941. Most of the score consisted of original compositions by the Swiss composer Paul Burkhard; the rest had been arranged by him. The musicians were placed in view of the audience so that they could be seen, one of Brecht’s many techniques in Epic Theatre. Therese Giehse, a well-known actress at the time, took the title role.[citation needed]

The second production of Mother Courage took place in then East Berlin in 1949, with Brecht’s (second) wife Helene Weigel, his main actress and later also director, as Mother Courage. Paul Dessau supplied a new score, composed in close collaboration with Brecht himself. This production would highly influence the formation of Brecht’s company, the Berliner Ensemble, which would provide him a venue to direct many of his plays. (Brecht died directing Galileo for the Ensemble.) Brecht revised the play for this production in reaction to the reviews of the Zürich production, which empathized with the “heart-rending vitality of all maternal creatures”. Even so, he wrote that the Berlin audience failed to see Mother Courage’s crimes and participation in the war and focused on her suffering instead.[9]

The next production (and second production in Germany) was directed by Brecht at the Munich Kammerspiele in 1950, with the original Mother Courage, Therese Giehse, with a set designed by Theo Otto (see photo, above.)[citation needed]

In Spanish, it was premiered in 1954 in Buenos Aires with Alejandra Boero and in 1958 in Montevideo with China Zorrilla from the Uruguayan National Comedy Company. In this language, the main character has also been played by actresses Rosa María Sardá (Madrid, 1986), Cipe Lincovsky (Buenos Aires, 1989), Vicky Peña (Barcelona, 2003), Claudia Lapacó (Buenos Aires, 2018) and Blanca Portillo (Madrid, 2019).[citation needed]

In other languages, it was played by famous actresses as Simone Signoret, Lotte Lenya, Dorothea Neff (Vienna, 1963), Germaine Montero, Angela Winkler, Hanna Schygulla, Katina Paxinou (Athens, 1971), Maria Bill (Viena), María Casares (París, 1969), Eunice Muñoz (Lisbon, 1987), Pupella Maggio, Liv Ullmann (Oslo), Maddalena Crippa (Milán), etc.[citation needed]

In 1955, Joan Littlewood‘s Theatre Workshop gave the play its London première, with Littlewood performing the title role.[citation needed]

In June 1959 the BBC broadcast a television version adapted by Eric Crozier from Eric Bentley’s English translation of the play. Produced by Rudolph Cartier; it starred Flora Robson in the title role.[citation needed]

The play remained unperformed in Britain after the 1955 Littlewood production until 1961 when the Stratford-upon-Avon Amateur Players undertook to introduce the play to the English Midlands. Directed by American Keith Fowler and presented on the floor of the Stratford Hippodrome, the play drew high acclaim.[10] The title role was played by Elizabeth (“Libby”) Cutts, with Pat Elliott as Katrin, Digby Day as Swiss Cheese, and James Orr as Eiliff.[10]

The play received its American premiere at Cleveland Play House in 1958, starring Harriet Brazier as Mother Courage. The play was directed by Benno Frank and the set was designed by Paul Rodgers.[11]

The first Broadway production of Mother Courage opened at the Martin Beck Theatre on 28 March 1963. It was directed by Jerome Robbins, starred Anne Bancroft, and featured Barbara Harris and Gene Wilder. It ran for 52 performances and was nominated for four Tony Awards.[12] During this production Wilder first met Bancroft’s then-boyfriend, Mel Brooks.[13]

In 1971 Joachim Tenschert directed a staging of Brecht’s original Berliner Ensemble production for the Melbourne Theatre Company at the Princess Theatre.[14] Gloria Dawn played Mother Courage; Wendy Hughes, John Wood and Tony Llewellyn-Jones her children; Frank Thring the Chaplain; Frederick Parslow the cook; Jennifer Hagan played Yvette; and Peter Curtin.[citation needed]

In 1980 Wilford Leach directed a new adaptation by Ntozake Shange at The Public Theater. This version was set in the American South during Reconstruction.[15] Gloria Foster played Mother Courage in a cast that also included Morgan Freeman, Samuel L. Jackson, Hattie Winston, Raynor Scheine, and Anna Deavere Smith.[citation needed]

In May 1982 at London’s Theatre Space Internationalist Theatre[16] staged a multi-ethnic production of Mother Courage[17] “whose attack on the practice of war could not— with South Atlantic news (Falklands War) filling the front pages— have been more topical..”[18] “The cast … is made of experienced actors from all over the world and perhaps their very cosmopolitanism helps to bring new textures to a familiar dish”.[19] Margaret Robertson[20] played Mother Courage, Milos Kirek the Cook, Renu Setna the Chaplain, Joseph Long the Officer, Angelique Rockas Yvette, and Josephine Welcome Kattrin.[citation needed]

In 1984 the Royal Shakespeare Company staged Mother Courage at the Barbican Theatre in London with Judi Dench in the title role and Zoë Wanamaker as Katrin.[citation needed]

In 1995–96, Diana Rigg was awarded an Evening Standard Theatre Award for her performance in the title role, directed by Jonathan Kent, at the National Theatre. David Hare provided the translation.[21][22]

From August to September 2006, Mother Courage and Her Children was produced by The Public Theater in New York City with a new translation by playwright Tony Kushner. This production included new music by composer Jeanine Tesori and was directed by George C. Wolfe. Meryl Streep played Mother Courage with a supporting cast that included Kevin Kline and Austin Pendleton. This production was free to the public and played to full houses at the Public Theater’s Delacorte Theater in Central Park. It ran for four weeks.[citation needed]

This same Tony Kushner translation was performed in a new production at London’s Royal National Theatre between September and December 2009, with Fiona Shaw in the title role, directed by Deborah Warner and with new songs performed live by Duke Special.[citation needed]

In 2013, Wesley Enoch directed a new translation by Paula Nazarski for an all-indigenous Australian cast at the Queensland Performing Arts Centre‘s Playhouse Theatre.[23]

In Sri Lanka, Mother Courage has been translated into Sinhalese and produced several times. In 1972, Henry Jayasena directed it as Diriya Mawa Ha Ege Daruwo and under the same name Anoja Weerasinghe directed it in 2006. In 2014, Ranjith Wijenayake translated into Sinhalese the translation of John Willet as Dhairya Maatha and produced it as a stage drama.[24][25][full citation needed]

Brecht’s reaction[edit]

After the 1941 performances in Switzerland, Brecht believed critics had misunderstood the play. While many sympathized with Courage, Brecht’s goal was to show that Mother Courage was wrong for not understanding the circumstances she and her children were in. According to Hans Mayer, Brecht changed the play for the 1949 performances in East Berlin to make Courage less sympathetic to the audience.[26] However, according to Mayer, these alterations did not significantly change the audience’s sympathy for Courage.[26] Katie Baker, in a retrospective article about Mother Courage on its 75th anniversary, notes that “[Brecht’s audiences] were missing the point of his Verfremdungseffekt, that breaking of the fourth wall which was supposed to make the masses think, not feel, in order to nudge them in a revolutionary direction.” She also quotes Brecht as lamenting: “The (East Berliner) audiences of 1949 did not see Mother Courage’s crimes, her participation, her desire to share in the profits of the war business; they saw only her failure, her sufferings.”[27]

Popular culture[edit]

The German feminist newspaper Courage, published from 1976 to 1984, was named after Mother Courage, whom the editors saw as a “self-directed woman … not a starry-eyed idealist but neither is she satisfied with the status quo”.[28]

The character of Penelope Pennywise in the Tony Award-winning musical Urinetown has been called “a cartoonish descendant of Brecht’s Mother Courage”.[29]

Mother Courage has been compared to the popular musical, Fiddler on the Roof. As Matthew Gurewitsch wrote in The New York Sun, “Deep down, Mother Courage has a lot in common with Tevye the Milkman in Fiddler on the Roof. Like him, she’s a mother hen helpless to protect the brood.”[30]

Mother Courage was the inspiration for Lynn Nottage‘s Pulitzer winning play Ruined,[31] written after Nottage spent time with Congolese women in Ugandan refugee camps.[32]

English versions[edit]

- 1941 – Hoffman Reynolds Hays (1904–1980), translation for New Directions Publishing

- 1955 – Eric Bentley, translation for Doubleday/Garden City

- 1965 – Eric Bentley, translation, and W. H. Auden, songs translation, for the National Theatre, London

- 1972 – Ralph Manheim, translation for Random House/Pantheon Books

- 1980 – John Willett, translation for Methuen Publishing

- 1980 – Ntozake Shange, adaptation for New York Shakespeare Festival New York

- 1984 – Hanif Kureishi, adaptation, and Sue Davies, songs translation, for the Barbican Centre, London (Samuel French Ltd.)

- 1995 – David Hare, adaptation for the Royal National Theatre, London (A & C Black, 1996)

- 2000 – Lee Hall, adaptation, and Jan-Willem van den Bosch, translation, for Yvonne Arnaud Theatre, England (Methuen Drama, 2003)

- 2006 – Michael Hofmann, adaptation, and John Willett, songs translation, for the English Touring Theatre (A & C Black, 2006)

- 2006 – Tony Kushner, adaptation for The Public Theater, New York City, published in the form used in the 2009 Royal National Theatre production

- 2014 – David Hare, adaptation presented by the Arena Stage, Washington DC with Kathleen Turner as Mother Courage and featuring 13 new songs.[33]

- 2014 – Wesley Enoch, adaptation, Queensland Theatre Company

- 2014 – David Edgar, translation for Stratford Festival, directed by Martha Henry

- 2015 – Ed Thomas for National Theatre Wales, site specific production with an all-female cast held at the Merthyr Tydfil Labour Club

- 2015 – Eamon Flack, adaptation, Belvoir St Theatre, Sydney.

- 2017 – Danielle Tarento direction of the Tony Kushner adaptation, Southwark Playhouse, London.

- 2019 – Adaptation by Anna Jordan for the Royal Exchange theatre, Manchester UK. Starring Julie Hesmondhalgh as Mother Courage.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Brecht Chronik, Werner Hecht, editor. (Suhrkamp Verlag, 1998), p. 566.

- ^ Oskar Eustis, “Program Note” for the New York Shakespeare Festival production of Mother Courage and Her Children, starring Meryl Streep, August 2006.

- ^ Brett D. Johnson, “Review of Mother Courage and Her Children,” Theatre Journal, Volume 59, Number 2, May 2007, pp. 281–282.

- ^ Klaus Volker. Brecht Chronicle. (Seabury Press, 1975). P. 92.

- ^ “Introduction”, Bertolt Brecht: Collected Plays, vol. 5. (Vintage Books, 1972), p. xi

- ^ Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen. “Die Lebensbeschreibung der Erzbetrügerin und Landstörzerin Courasche”. gutenberg.spiegel.de.

- ^ Oscar Eustis (Artistic Director of the New York Shakespeare Festival), Program Note for N.Y.S.F. production of Mother Courage and Her Children with Meryl Streep, August 2006.

- ^ Bertolt Brecht. Brecht on Theatre, Edited by John Willett. p. 121.

- ^ For information in English on the revisions to the play, see John Willet and Ralph Manheim, eds. Brecht, Collected Plays: Five (Life of Galileo, Mother Courage and Her Children), Metheuen, 1980: 271, 324–5.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Shout it from the Rooftops”, Stratford-upon-Avon Herald, April 1961.