Indians: The Aryans and the Vedic Age

More than a thousand years after the Harappans, the next cities arose in the Gangetic Plain in mid-first millennium BCE. Episode two of the series focuses on them.

After the decline of the Harappan Civilisation, waves of Aryan migrants arrived from Central Asia between 2000-1500 BCE. A nomadic-pastoralist people of lighter skin, the Aryans were culturally different from the Subcontinent’s settled farmers and forest tribes of darker skin. They brought along an early Sanskrit, proto-Vedas, Vedic gods, a priestly class fond of fire rituals and oral chants, new social and gender hierarchies, the horse and chariot.

Mixing with the locals forged a lighter-skinned elite that spoke Indo-European languages, or Prakrits. In the centuries ahead, larger political units led by tribal chiefs emerged in north India. War among Aryanized tribes like the Bharatas and Purus became common. From this substrate and its social conflicts came the early stories of the Mahabharata, c. 1000 BCE. Indo-Aryan culture and languages became dominant in Aryavarta, whose cultural and material qualities I’ll explore in this episode.

More than a thousand years after the Harappans, the next cities arose in the Gangetic Plain in mid-first millennium BCE. New states with money economies even flirted with democratic ideas. New hybrid cultures arose from the mixing of Indo-Aryans, post-Harappans, and ethnic groups whose ancestors had come to India much earlier. They forged new trades, lifestyles, and a thriving marketplace of spiritual and religious ideas. This prolific age – of the early Upanishads, the Buddha, Mahavira, Carvaka, Panini – would profoundly shape later Indians.

| INDIANS | A History Web Series | SERIES HOME |

Research, Script and Narration by Namit Arora

Producer: The Wire; Director: Natasha Badhwar; Camera: Ajmal Jami; Video Editor: Anam Sheikh

Made possible by a grant from The Raza Foundation and contributions to The Wire by viewers like you.

| The story of India is one of profound and continuous change. It has been shaped by the dynamic of migration, conflict, mixing, coexistence, and cooperation. In this ten-part web series, I’ll tell the story of Indians and our civilization by exploring some of our greatest historical sites, most of which were lost to memory and were dug out by archaeologists. I’ll also focus on ancient and medieval foreign travellers whose idiosyncratic accounts conceal surprising insights about us Indians. All along, I’ll survey India’s long and exciting churn of cultural ideas, beliefs, and values—some that still shape us today, and others that have been lost forever. The series mostly mirrors—and often extends—the contents of my book, Indians: A Brief History of a Civilization. Bibliography and transcript appear below. Go ahead and watch! —Namit Arora Episode 2: The Aryans and the Vedic Age (28 mins)Short 1 https://www.youtube.com/embed/rrBoZrhv3Y4?si=nOujZbyWOz-SDpGYAfter the decline of the Harappan Civilization, waves of Aryan migrants arrived from Central Asia between 2000–1500 BCE. A nomadic-pastoralist people of lighter skin, the Aryans were culturally different from the Subcontinent’s settled farmers and forest tribes of darker skin. They brought along an early Sanskrit, proto-Vedas, Vedic gods, a priestly class fond of fire rituals and oral chants, new social and gender hierarchies, the horse and chariot. Mixing with the locals forged a lighter-skinned elite that spoke Indo-European languages, or Prakrits. In the centuries ahead, larger political units led by tribal chiefs emerged in north India. War among Aryanized tribes like the Bharatas and Purus became common. From this substrate and its social conflicts came the early stories of the Mahabharata, c. 1000 BCE. Indo-Aryan culture and languages became dominant in Aryavarta, whose cultural and material qualities I’ll explore in this episode.More than a thousand years after the Harappans, the next cities arose in the Gangetic Plain in mid-first millennium BCE. New states with money economies even flirted with democratic ideas. New hybrid cultures arose from the mixing of Indo-Aryans, post-Harappans, and ethnic groups whose ancestors had come to India much earlier. They forged new trades, lifestyles, and a thriving marketplace of spiritual and religious ideas. This prolific age—of the early Upanishads, the Buddha, Mahavira, Carvaka, Panini—would profoundly shape later Indians. |

| PARTIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY / FURTHER READINGAnthony, David W, The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World, Princeton University Press, 2010Basu, A and Sarkar-Roy, N, Majumder PP, ‘Genomic reconstruction of the history of extant populations of India reveals five distinct ancestral components and a complex structure’, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016 Feb 9; 113(6):1594-9Bryant, Edwin, The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate, OUP, 2001Devy, G N, Mahabharata: The Epic and the Nation, Aleph Book Company, 2022 Doniger, Wendy, The Hindus: An Alternative History, Penguin, 2009Jha, D.N., The Myth of the Holy Cow, Navayana, 2010Joseph, Tony, Early Indians, Juggernaut, 2018Khan, Razib, The character of caste; Stark Truth About Aryans: a story of India; Stark Truth About Humans: a story of India, ‘Unsupervised Learning’ Substack, 2021Kristiansen, K., Kroonen, G., & Willerslev, E. (Eds.), The Indo-European Puzzle Revisited: Integrating Archaeology, Genetics, and Linguistics. CUP, 2023Kuz’mina, Elena E., The Origin of the Indo-Iranians, Brill, 2007 Mohan, Peggy, Wanderers, Kings, Merchants: The Story of India through Its Languages, Penguin, 2021Modi, Jivanji Jamshedji, ‘The antiquity of the custom of Sati’, Anthropological Papers, 1929, Part IV: Papers read before the Anthropological Society of Bombay: British India Press, Seite 109–21Ollett, Andrew, Language of the Snakes: Prakrit, Sanskrit and the language order of premodern India, UC Press, 2017 Olsen, Birgit Anette (Editor) et al, Tracing the Indo-Europeans: New evidence from archaeology and historical linguistics, Oxbow Books, 2019Parpola, Asko, The Roots of Hinduism, Oxford University Press, 2015, p. 96–7Reich, David, Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the new science of the human past, OUP, 2018Sen, Sudipta, Ganga: The Many Pasts of a River, Gurgaon, Viking, 2019Shinde, Vasant, et al., ‘An Ancient Harappan Genome Lacks Ancestry from Steppe Pastoralists or Iranian Farmers’, Cell, Vol 179, Issue 3, October 17, 2019Silva, Marina, et al., ‘A genetic Chronology for the Indian Subcontinent Points to Heavily Sex-biased Dispersals’, BMC Evolutionary Biology, 2017Singh, Upinder, Political Violence in Ancient India, Harvard University Press, 2017Tagore, Debashree, et al, Multiple migrations from East Asia led to linguistic transformation in NorthEast India and mainland Southeast Asia, Frontiers in Genetics, 11 Oct 2022 Thapar, Romila, Early India, Penguin, 2002Thapar, Romila, et al, Which of Us Are Aryans?, Aleph Book Company, 2019 |

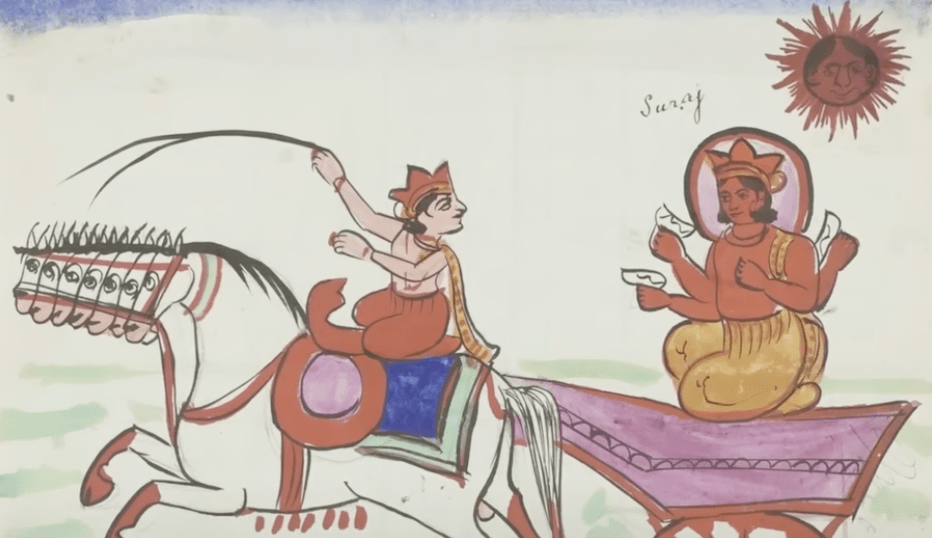

| EPISODE TRANSCRIPTHello and welcome to Indians. I’m Namit Arora.In the previous episode, we looked at the rise and fall of the Harappan Civilization in the northwest of the Indian Subcontinent. Its decline was most likely caused by regional climate change. A long spell of bad monsoons led to droughts and drove urban Harappans out of their towns and cities. By 1900 BCE, a lot of Harappans had migrated south and east, where they dissolved into the rural life of the subcontinent.Indo-Aryans and Their Culture Around this time, a brand-new group entered India from Central Asia. They called themselves the Arya, meaning, ‘the noble ones’. Not exactly a winning move in a humility contest. They came in multiple waves between 2000–1500 BCE. This influx of the Aryans would become one of the most significant cultural influences on the subcontinent. Their arrival marked the rise of what historians call the Vedic Age, lasting until about 500 BCE—and that’s the period we’ll look at in this episode.These Aryans, or Indo-Aryans, were mainly nomadic herders & their culture was profoundly different from that of the Harappans and their descendants, who were settled farmers. The Aryans rode horses and horse-drawn chariots; the Harappans never used horses. The Aryans had a three-tiered social stratification—between priests, warriors, and commoners—whereas no such division is known among the Harappans. The religious cosmology of the Aryans had mostly male gods, such as Indra, Varuna, Surya, Mitra, Agni, Vayu, Rudra. They had a few female ones too, such as Usha and Sarasvati—but their presence is quite insignificant compared to the presence of women in the artefacts of the subcontinent, as we saw in the previous episode.The Aryans spoke an early form of Sanskrit, called Vedic Sanskrit. Their oral tradition included early forms of the verses of the Rig Veda. A priestly class of Brahmins performed fire rituals and oral chants. They memorised and passed down their magical words and sounds with great precision. The Aryans sacrificed animals to their gods, including cattle, goats, and horses. The Ashwamedh yagya, a ritual performed by ambitious kings, usually ended with a horse sacrifice. Like other nomadic herders, the Aryans killed and ate male calves as well as older cows that no longer gave milk. As Swami Vivekananda wrote, ‘There was a time in this very India when, without eating beef, no Brahmin could remain a Brahmin’.But the milk-giving cow also had an elevated and protective status compared to other animals. In other words, the Aryans saw the cow as special, but they also slaughtered her when she was no longer useful. Her special status came from their Central Asian ancestors. Interestingly, the Aryans met the domesticated water buffalo in India, but denied her the same high status, despite being no less useful. Poor buffalo!As part of their rituals, the Aryans also had some fun. They drank an intoxicant called soma. Their gods, esp. Indra and Agni, are also described as drinking soma in large quantities. The psychedelic highs of soma were surely quite enjoyable, but for the most part, Vedic religion was ritualistic and sacrificial. It did not yet have ideas like the cycle of samsara, maya, karma, or moksha. From this Vedic religious substrate and the social hierarchy of the Vedic Aryans would later emerge Brahminism and the four-fold varna system.Indo-Aryans’ Interactions With the Locals What happened next is super interesting. The incoming Aryans were a relatively powerful and aggressive group. They started settling down and mixing with the locals. Their chariots and their dramatic fire rituals with hypnotic incantations must have mesmerised the locals. The Aryans were light-skinned while the locals were dark-skinned. A common custom among Aryan men was to take many wives. Genetic studies suggest that Aryan men reproduced with local women at extremely high rates. This would have required displacing or eliminating many local men. It’s hard to imagine this happening through some kind of happy cultural exchange between equals. More likely, violence and coercion were involved. Many local women were probably abducted, and most locals would have seen the Indo-Aryans as aggressive intruders. Voluntary or not, all this genetic mixing began creating a new social elite with lighter skin tones than the rest of the population.Within a few generations, the Indo-Aryans, and this new mixed elite with lighter skin, became a force to reckon with. In a way the Indo-Aryan strategy was very effective. Through mating, aggressive power, or cultural diffusion, they colonized the minds of a local elite to establish themselves, much like what the Turko-Persians and the British did later. This local elite then started championing Indo-Aryan culture, religion, and language. This became a path to upward mobility in the emerging social order.But it also seems natural that other locals must have resented the growing domination of the alien Indo-Aryan culture. There must’ve been conflicts, but we don’t know what form they took. In parallel, ethnic mixing and internal migration also continued for over a thousand years. This eventually produced a new social layer that still lives on, especially in the upper caste groups of north India. These groups derive as much as 30 percent of their paternal ancestry from the Indo-Aryans, compared to low single digits for Dalits and Adivasis of South India.The Roots of the Indo-Aryans Modern genetics has traced the roots of the Indo-Aryans to the Yamnaya people, who lived in the steppes, which are grasslands now in southern Russia and Ukraine. Earlier descendants of the Yamnaya had gone to Europe and West Asia, and later ones came to India. That’s why Zeus, the king of the Greek gods, is so similar to Indra, the king of the Vedic gods. It appears that many descendants of the Yamnaya had a social hierarchy based on three classes. They ritually sacrificed cows and horses, a practice the Indo-Aryans inherited. The Yamnaya also spoke a proto-Indo-European language from which descend all the languages of the Indo-European family, such as Greek, Latin, Persian, Sanskrit, German, and English.Indo-Aryan Patriarchy Ancient DNA from Indo-European burial sites have revealed their kinship structures, including marital norms. They confirm that Yamnaya lineages were very patriarchal. Take the Indo-Aryans. As I noted earlier, some of their men were super successful in passing on their genes in north India, very likely through violence. They kept women in secondary roles and out of ceremonial rituals. It’s true that a few women, mostly wives or daughters of prominent sages, do appear in the Vedas. Gargi and Maitreyi come to mind, but they were the exceptions.Several Yamnaya lineages, including the Indo-Aryans, are known to have valued Sati. This gory ritual of burning widows on the funeral pyres of their dead husbands appeared not just in India but in many parts of the world, notably Europe. The father of Alexander the Great had a Thracian wife who, as part of a custom of her people, was burned on her husband’s funeral pyre. The first known mentions of Sati in India are also from the same timeframe: 4th century BCE. It’s just that other regions got rid of the practice of Sati long before Indians did. So it’s fair to say that the Indo-Aryans brought with them a far more subordinate idea of women than what had prevailed in the Subcontinent.The mixing of Indo-Aryans with local women had other outcomes too. One was that Vedic Sanskrit, spoken by Aryan men, began absorbing loanwords from the languages of their local wives. It also absorbed a specific set of sounds called retroflex (such as ट, ठ, ड, ढ, ण). You hear them in words like thik, danda, dhona, bara. These sounds are produced when the tip of your tongue curls upwards to touch the palate. These retroflex sounds are unique to the languages of the subcontinent, and they soon also entered Sanskrit.The Aryan Controversy Today Allow me to digress a little to talk about a contentious debate in India today. Somehow, the idea of Aryans migrating into India has faced great resistance in recent decades. Almost all of it comes from Hindu nationalists. And it’s not hard to understand why. They want to see the Aryans as indigenous to India because they want to see Vedic Hinduism as indigenous to Indian society. It’s important to their political ideology that cultural elements like Sanskrit, the Rig Veda, and priestly fire rituals are shown as native to India. And so, despite all the evidence, Hindu nationalists insist that the Harappans and the Aryans were one people who spoke Sanskrit. They even see Sanskrit as the mother of all Indo-European languages. They favor the so-called Out-of-India Theory, in which the Aryans originated in India and went out from here to give Indo-European languages to the world. These nationalists see the roots of Hindu religion as entirely ‘native’, contrasting it with the ‘outsider’ roots of Islam and Christianity. In their mind, this bolsters their claim of India being a ‘Hindu nation’.Fortunately, the science of ancient DNA has now firmly resolved this so-called ‘debate’ about the origin of the Indo-Aryans. Scholars in the field, based on evidence from linguistics and archaeology, have long supported the Aryan Migration Theory. Now the study of ancient DNA has revealed our genetic lineages and migration patterns going back thousands of years.And today, there is little scholarly disagreement about this—Aryan Migration is a fact, not an opinion. What this also means is that to the extent the Rig Veda, Sanskrit, and priestly fire rituals are seen as the foundations of Hinduism, to that extent Hinduism too is an outsider religion, arriving with the Aryans from Central Asia.Here is a side note. It’s important to realize that the Aryan Migration Theory is different from the earlier model proposed by the British—the Aryan Invasion Theory—which was abandoned by scholars many decades ago. The Aryans, it’s now clear, came into India over the course of many centuries. And their incoming population was dominated by men. They came with their animal herds and settled across north India. Scholars do not see the patterns of a statist military invasion in it. In other words, the Aryans are best classified as migrants, not invaders, though they surely had many conflicts with the locals, and some locals may have experienced them as invaders. One thing we can be absolutely sure of: Never in their wildest dreams could these Aryans have imagined that three thousand and five hundred years later, people would be excitedly discussing them and fighting a culture war over their legacy!An Era of Cultural and Genetic Mixing Ok, back to my narrative. We were talking about a great deal of genetic and cultural mixing between Indo-Aryans and local groups. There was much internal migration. From this churning and mingling came new hybrid cultures. This is also the start of the Iron Age in India. Between 1500–1100 BCE, larger political units led by warlike chieftains began coming up, mostly in the fertile Ganga Plains. War between these Aryanized tribes, such as the Bharatas and Purus, became a regular feature in the region. These Bharatas would later inspire the geographic terms Bharat and Bharatvarsha.From this substrate and its social conflicts came the early stories of the Mahabharata, around 1000 BCE. The earliest bards who told the Mahabharata story may have been charioteers, who served as drivers, confidantes, and bodyguards to the warriors. While on military campaigns, they recited stories around campfires. No wonder God was a charioteer in the epic! Even Karna was raised by a charioteer. Starting with a king and a fisherwoman as the founders of the Kuru clan, these stories would evolve over centuries, as they would be told and retold in countless venues. Each new generation of oral storytellers would add new and exciting masala into it—to a point where it’s now very hard to extract any reliable historical data from it. Despite that, the stories of the Mahabharata arguably contain a psychic record of the late Vedic Age. It records its evolving values, morals, anxieties, as well as notions of dharma, time, honor, and so on. This great epic also contains echoes of a changing social order, which was moving away from tribal and clan-based units towards becoming hereditary kingdoms ruled by a warrior class.After the arrival of the Indo-Aryans, no cities arose in India for centuries. The Harappan script had disappeared along with their cities, and no other script has been found. It’s intriguing that the flame of a literate urban civilization wasn’t lit again for over a thousand years. Perhaps the lack of an urban civilization reduced the need for a script. But while there were no cities or scripts, many cultures kept evolving in the subcontinent. Archaeologists identify them through their pottery and other artefacts, such as Ochre Colored Pottery Culture, Copper Hoard Culture, and Painted Grey Ware Culture. The Pandavas and Kauravas of the Mahabharata would have used such Painted Grey Ware pottery.Aryavarta Emerges In the late Vedic Age, from 1100–500 BCE, a large part of north India was called Aryavarta, the land of the Aryans, in which Indo-Aryan culture and languages had become dominant. Brahminism had become the religion of the social elites, but it still reached only a minority of people. In this social set—and spilling beyond it—the four varna categories as well as ritual purity and pollution had become common concepts.But there is no evidence yet of a caste system, which is about a hierarchy of endogamous groups. Endogamy means marrying within one’s own social group. The caste system emerged later when Aryanized notions of purity and pollution got mapped onto occupations and produced both endogamy and hierarchy.Beyond Aryavarta, on all sides, lived the barbarians, or the mleccha. This term included foreigners to the north as well as people south of the Vindhyas and forest peoples, who had very different customs and languages. In popular stories, such people were often imagined as subhuman creatures, grotesque rakshasas, fierce-looking demons, or talking monkeys!Evolution of Prakrits Across the north, the ethnically mixed Indo-Aryan elite forged new languages too. We call them Middle Indo-Aryan languages, or prakrits. Examples include Magadhi, Maharashtri, Shauraseni, Pali, Gandhari. In their grammar and vocabulary, these prakrits were close to Vedic Sanskrit, except that they had the accents, loan words, and idioms of vernacular languages.In a way, Indian English is also a prakrit, created by upper-class Indian speakers of British English. Same process! By the late Vedic Age, prakrits were increasingly spoken by the middle and upper classes of the day, while the poor and rural folk continued with their old vernacular languages. Over time, the prakrits and Indo-Aryan culture gained in the north. By the medieval period, this process would practically wipe out all vernacular languages of north India, replacing them with various Indo-Aryan languages. Interestingly, we now call these Indo-Aryan languages vernacular in relation to English.Meanwhile, in the south, Dravidian languages and post-Harappan and other folk cultures became prominent. Something of this cultural divide still exists in India.Rise of Mahajanapadas In the centuries ahead, forests were cleared, and agriculture expanded. New modes of life, specialized trades and professions arose. New states like Kosala, Kamboja, Kashi, Rajagriha, Malla, and Vaishali emerged in north India. Many of them had developed money economies, with coins as legal tender. Some of these states even experimented with democratic ideas, similar to those in Greece.The thing is that if Greece can be called the mother of democracy, so can India. Truth is that both the Indian and the Greek experiments were closer to city scale and not very democratic by modern yardsticks. They were in fact closer to oligarchic republics. Yet, they both belong to a plural prehistory of democracy, whose examples can be found around the world, not just in India and Greece. What’s common to them is their taste for governance through discussion, debate & voting by a wider cross-section of people. Sadly, as in Greece, these early experiments in India soon collapsed and gave way to monarchies. Indians abandoned these early democratic instincts for 2500 years and embraced new social hierarchies. Only in modern times would a class of Indians re-cultivate a taste for democracy after India’s collision with Europe.India’s Axial Age By around 500 BCE, fertile river valleys supported urban centres quite different from those of the urban Harappans. These had been shaped by new hybrid cultures created by the mixing of Indo-Aryans, Harappans, and other ethnic groups that had long been in India. Together they gave rise to new trades, lifestyles, and a thriving marketplace of spiritual and religious ideas.Even in hindsight, this was one of the most prolific and creative ages in India. Its own Axial Age that would profoundly shape later Indians. It was the age of the Upanishads, which departed from the earlier ritualistic and sacrificial Vedas. The Upanishads were more abstract, inner-directed, and contemplative.It was the age of the Buddha, who spoke of human suffering and compassion, injecting a huge moral dimension in Indian religious thought.It was the age of the Carvakas, the materialists who rejected all afterlife and the Vedas, which they claimed were designed to keep men submissive through fear and rituals. The Carvakas were atheists who mocked religious ceremonies, calling them inventions of the Brahmins to ensure their own livelihood.It was the age of Mahavira, who took the idea of non-violence to new heights. The age of Panini, the grammarian from Gandhara who forged the classical form of Sanskrit. The age of early medical surgeries that could reconstruct noses chopped off as punishment. Of course, one wonders why so many people had their noses chopped off to create a market for this surgical expertise. Chances are that it had something to do with the rise of new regimes of coercive power in centralized state societies, often at war with each other.The Brahmi Script Curiously, all this amazing innovation in thought and deed somehow happened without a written script! —or at least a script that we know of. The earliest firm evidence of a script in India, a script called Brahmi, comes from Ashoka’s edicts of third century BCE. Some scholars have argued that this script arose earlier and evolved for a couple of centuries but was written on materials that have not survived.Still, it’s amazing to think that the entire Vedic corpus was composed and transmitted orally for over a thousand years! Their shlokas required precise pronunciation for their magic to happen, so the Brahmins invested a great deal in memorizing them precisely. They were passed down orally from father to son for over 50 generations! That’s an impressive feat of organized memory!A New Religious Landscape Until the rise of Buddhism, Brahminism had the greatest hold on the elites of Aryavarta. But it reached only a small minority of the population. While Brahminism was based on the authority of the Vedas, others like Buddhists, Jains, Carvakas, and Ajivikas rejected the authority of the Vedas. For that reason, they were called nastika, or members of ‘heterodox traditions’ in later classifications of Indian philosophy. Interestingly, both Buddhism and Jainism arose at the eastern edges of Aryavarta, and had their most durable spread also in the east, down Odisha and Andhra Pradesh. Though their founders came from Aryanized groups, these heterodox religions were shaped more by non-Aryan spiritual substrates in the Subcontinent. Which also helps explain their differences and rivalries with Brahminism. More on that later in the series.In the next episode, I’ll look at the invasion of Alexander the Great and the rise of the first mega empire in India, founded by Chandragupta Maurya. I’ll look at it especially through the eyes of Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador to his court. See you next time! |

Full transcript

Hello and welcome to Indians. I’m Namit Arora.

In the previous episode we looked at the coming of the Aryans and the Vedic Age. After centuries of ethnic mixing and migration, Indians once again developed a taste for cities and urban life, around 2500 years ago. It produced a new age of social, intellectual, and religious innovation, and major cultural milestones like the Upanishads, the Buddha, Mahavira, the Carvakas, Panini, and more.

Alexander’s Invasion

Shortly after this came a major new force—the Greek invasion of the Punjab in 326 BCE. It was led by Alexander the Great, who came down the Khyber Pass with his army of 50,000 seasoned warriors. As he entered modern day Pakistan, king Ambhi of Taxila saw the writing on the wall and promptly surrendered. But another king challenged Alexander. His name, Porus, appears only in Greek sources. They fought a huge war by the river Jhelum. Alexander defeated Porus but suffered heavy losses. Impressed by Porus’s bravery and dignity in defeat, Alexander restored his kingdom to him.

This encounter between Porus and Alexander, who is also known as Sikandar in India, has been depicted in Hindi cinema twice, in the films Sikandar in 1941 and Sikandar-e-Azam in 1965. They captured the imagination of Indians by projecting modern nationalist passions into ancient settings: Porus was turned into a patriot defending Bharat mata, and Ambhi was declared a traitor. They’re best seen today as unintentional comedies.

Even though his army had shrunk, Alexander wanted to keep going all the way to the Ganga, but his troops rebelled. They had heard rumours of the Nanda Empire’s massive army. So Alexander reluctantly turned back from what is now Amritsar, and died on his way back to Greece. He was only in his early 30s. After his death, his generals fought each other for territorial control, and set up independent kingdoms and empires of their own.

Chanakya and Chandraguptra Maurya

A few years after Alexander’s death, two people in the northwest got together. The first was a Brahmin called Chanakya, variously described as brilliant, ruthless, and devious. The second was an ambitious warrior called Chandragupta Maurya. Historical sources ascribe “humble origins” to Chandragupta, suggesting that he may have been a Shudra. The two men forged alliances with other kings, assembled a large army, and fought a brutal war with the Nanda king, who ruled from Pataliputra, near Patna. Chandragupta won the war and established the Mauryan Empire, with its capital also at Pataliputra.

Megasthenes, the Ambassador

When the dust settled, to the west of the Mauryan Empire was the Seleucid Empire, stretching from Afghanistan to Turkey. The Seleucid emperor, Seleucus Nicator, was Greek. As part of a peace treaty with Chandragupta, he offered his daughter, Helena, in marriage. Chandragupta sent back 500 elephants as a gift. Seleucus also sent Megasthenes as his ambassador to Chandragupta’s court.

Megasthenes has left behind a fascinating account of his time in India, even though parts of it are unreliable and seem outlandish. That’s because he seems to have written down both what he saw and what he heard. Sometimes he uncritically recorded tall tales that his native informants told him. Among these are absurd stories of people with bizarre physical features, like earlobes stretching down to their feet, men with only one eye on their foreheads, and so on. Megasthenes is much better on Pataliputra, where he stayed for at least a couple of years, around 300 BCE. This part of his account is based more on his direct observation and experience.

Mauryan Empire According to Megasthenes

So what did Megasthenes observe? He wrote that Pataliputra was a giant city located by the Ganga. It extended 15 km along the riverfront and 3 km inland. Its size and population made it the largest city in the world. That’s not very surprising—India had a relatively large population even back then, thanks to its fertile plains, abundant rivers, and warm climate. Some estimates say the subcontinent then had about 30 million people. It then had a larger share of the global population than it does today.

But here is an amazing factoid. Just since the Mauryan period, India’s population has grown SEVENTY times! Seventy times in about two thousand years. Imagine how empty it must have felt back then. It’s like the Mauryans lived in a different country.

Megasthenes tells us that much of Pataliputra, including the king’s palace, was made of wood. This was not uncommon then for Indian cities located on floodplains. The city was surrounded by wooden walls and a moat. It had 570 watch towers, and 64 gates—averaging one gate every half a km. Archaeologists have found fragments of its wooden walls and a pillared hall of polished stone. But much of ancient Pataliputra is likely still beneath modern Patna—including what post-Mauryan dynasties later built in brick and stone.

With the Mauryan empire, we see the rise of the bureaucratic state, with officers in charge of trade, taxation, roads, markets, births and deaths, population census, and so on. They catalogued people based on their occupations and taxed them differently. What’s not clear is how far the state’s bureaucratic reach extended. The Mauryan Empire is conventionally shown as covering a huge area, but it included large autonomous regions where the reach of the state did not extend at all. Its actual sphere of influence may have been even smaller than in the map you see on the screen. It was likely based around a few urban centres in the subcontinent, such as Magadh, Gandhara, and Avanti. Much of India back then was forest land, where the locals hardly produced any surplus that an empire would want to control or tax. So it’s good to be sceptical of such evenly coloured maps of territorial unity or control.

In its urban zones, the Mauryan state was definitely a force to reckon with. It apparently had some aspects of the coercive authority and the surveillance regime described in the Arthashastra. This is a treatise on political statecraft attributed to Kautilya, who is often incorrectly equated with Chanakya. It was the work of multiple authors over centuries and is easily the most important work of political thought in ancient India, comparable to Aristotle’s Politics.

The Mauryan standing army was the largest India had ever seen. Megasthenes noticed that when the men of the army were not serving, ‘they spent their time in idleness and drinking bouts at the expense of the royal treasury.’

The land was fertile and enabled two harvests a year. People looked well fed, had a ‘proud bearing’ and were ‘well skilled in the arts.’ Theft was rare in Pataliputra. People often left their homes unguarded when they stepped out. Rich people wore expensive ornaments and fine cotton robes studded with gold work and precious stones. Polygamy, the practice of having more than one wife, was common in the upper class. Prostitution was legal; women in the profession were taxed and the state punished those who harmed them. Prostitution as a legal and taxable profession would remain common in Indian civilization. Many other foreign travellers noticed and wrote about it, as we’ll see in future episodes.

The Mauryans built a road between Pataliputra and Taxila, a precursor to the Grand Trunk Road. A significant proportion of their trade and transportation also happened on rivers. But much of the Mauryan state’s revenue was tied to land, not so much to trade. Megasthenes wrote that people could not buy or sell land. Why? Because all land belonged to the crown. People could use the land but not own it. This would remain the dominant system in India through ancient and medieval times, with some variants and exceptions around religious land grants. Farmers typically paid a land use tax plus a produce tax. In Mauryan times, farmers paid 25% of their produce to the king, plus a sales tax of 10%. Tax dodgers were severely punished.

But Brahmins and Buddhist monks had worked out a sweet deal—they were exempt from all taxes, whatever their income! This tax break to the priestly class would also become a persistent feature of Indian society.

Megasthenes on the Animals of India

Megasthenes took great interest in the land animals and birds of India. He was Greek so elephants were especially exotic to him, and he was fascinated by them. He saw them often because the giant army of the Mauryan state had lots of elephants. He studied them carefully … how they are captured, domesticated, used in war, and how their injuries are healed. He also wrote about a very interesting custom: When an elephant got angry, the Mauryans sang and played music before it to calm it down. Very much like the music therapy that’s offered nowadays in elephant sanctuaries in some parts of the world. Megasthenes also marvelled at parrots who would become, he wrote, ‘as talkative as children’.

Caste and Patriarchy as seen by Megasthenes

Megasthenes noticed a peculiar kind of social hierarchy in India, in which endogamous groups were seen as high and low—especially among the speakers of Indo-Aryan languages, or Prakrits. He wrote, ‘No one is allowed to marry out of his own group … or to exercise any calling or art except his own: for instance, a soldier cannot become a herder, or an artisan a philosopher.’ Clearly, this was not a free-wheeling division of labour but a division of labourers. What he had observed were not mere social classes but early castes. The spread of caste consciousness and patriarchy was then intimately tied to the spread of Indo-Aryan culture, and it was common enough in urban centres.

Already in 300 BCE, Megasthenes had observed that Brahmin men guarded their religious knowledge and did not share it with men of other castes, or with women—not even their own wives! What the ambassador had observed was very real. A stark patriarchy is plainly evident even in the Brahminical texts whose early versions were being written at this time, such as the Manusmriti and Arthashastra. These texts demanded chastity from women and total obedience to their husbands. Women were largely relegated to domestic and maternal roles. But while Brahminical society created such restrictions on women, Megasthenes observed that women were free to pursue philosophy with the Sramanas, which included the Buddhists, Jains, Ajivikas, and others.

It’s fair to say that in Mauryan times, Brahminism had already become the leading driver of patriarchy in the subcontinent. And it was about to get a lot worse as endogamy spread. Upper-caste women had it worse because their sexuality had to be more strictly controlled to maintain the sanctity of caste and ‘purity of blood’. Even the roots of child marriage and the prohibition on widow remarriage lie in the peculiar logic of caste and endogamy. In the 3rd century BCE, all this was still in its infancy and affected only a small minority in the subcontinent, but it would steadily gather steam in the centuries ahead.

Indo-Greek Cultural Exchanges

After Alexander, there was a freer flow of ideas between East and West. Indians gained in science—such as astronomy—and in the arts, especially with the syncretic Greco-Buddhist art of the Gandhara school. In return, Indian philosophy influenced many schools of Greek philosophy, such as Neoplatonism, Stoicism, and Pyrrhonism, which was a school of philosophical scepticism that rejected dogma. The sceptical tradition was not only alive and well in India, it was even inspiring sceptics in Greece!

Emperor Ashoka

Three decades after Megasthenes, Ashoka became the Mauryan emperor. His story is now well known, but for centuries, Indians had completely forgotten him. His story was recovered through archaeology and non-Indian texts in modern times. As with so much of our history, it’s probably best NOT to rely much on Bollywood to understand Ashoka’s life and times.

We now know that after a brutal war with Kalinga, Ashoka was pained by the suffering he had caused. His remorse led him to embrace Buddhism and its doctrines of nonviolence and compassion. By then, Buddhism had acquired a large urban following, though both Buddhism & Brahminism were still minority religions in the Subcontinent. That’s because most people still followed their animistic faiths and worshipped animals, trees, spirits, ancestors, and highly localised divinities of fertility, harvests, health, and so on.

But Ashoka’s urban subjects cared a great deal for Buddhism. So it was not a radical move for Ashoka to convert to Buddhism, or to send missions to spread it across India and beyond. Unlike Brahminism, Buddhism was a missionary religion equally open to all people. It devalued social hierarchies and held that everyone in the community had the same potential for spiritual attainment. At least in this respect, Buddhism was like Christianity and Islam, and this helped it gain followers across Asia.

What Ashoka’s Edicts Reveal

Ashoka’s edicts reveal his benevolent yet stern paternalism. ‘All men are my children,’ he said. He urged them to lead pious, gentle, and virtuous lives. A politician saying such things today may seem to us overbearing, but that’s a quibble. Ashoka’s personal inner transformation was rather impressive. He gave up armed conquest as part of his turn to nonviolence. He gave up hunting. He drastically cut down the killing of animals in his royal kitchen. He also made laws to reduce animal sacrifices, presumably by the Brahmins. He focused more on social welfare, as in building hospitals, tree-lined roads, and wells. He even made the treatment of prisoners more humane. Ashoka’s public embrace of non-violence was significant and likely unique among the world’s emperors.

Some scholars believe that even Arjuna’s reluctance to join the war in the Mahabharata was a plot twist inspired by Ashoka. That’s quite plausible. Arjuna expresses his moral doubts about the war in the Bhagavad Gita. The Gita is of course a much later addition to the Mahabharata. It’s almost as if, after Ashoka, the Brahminical class had to find retroactive justification for a war that also led to massive death and suffering in the epic. That justification is what Krishna tries to provide in the Gita, in contrast to the moral ambiguities about the war in the rest of the epic.

Having said that, we ought to keep things in perspective about Ashoka. There were surely gaps between his pronouncements and his practices. After all, he continued to maintain his armies, because can you run the business of empire without unnecessary violence? The empire had to grow by clearing forests for agriculture. Resistance and rivals had to be crushed. His rock edict #13 even issued a stern warning to the Adivasis of his day, asking them to behave or else be killed. These non-agricultural forest tribes were now part of a long and losing battle against expanding agricultural states in India.

Ashokan ‘Secularism’

Ashoka is interesting in another way. His public edicts can be called the earliest expressions of Indian secularism. In one edict, Ashoka claimed that he ‘honours all sects and both ascetics and laymen, with gifts and various forms of recognition.’ He also said that anyone who glorifies his own faith at the expense of other faiths only damages his own. True religious merit, he said, comes from harmonious coexistence with people of other faiths. This sentiment is in line with what would later become the Indian ideal of secularism, in which the state does not separate itself from religion but attempts to patronise all major religions. Ashoka promoted this idea of an inclusive and secular state, long before the term ‘Indian secularism’ came into being. Even for a small sect like that of the Ajivikas, he built the Barabar Hill Caves. In fact, Indian rulers have a long history of patronising multiple faiths—such as Ashoka, Kanishka, the Guptas, Harsha, the Palas, Akbar, and others. There are also counter examples.

The Rise of Monumental Art

It’s only from the Mauryan period in Indian history that we get monumental art and stunning sculpture. Examples here include the magnificent Sanchi Stupa, commissioned by Ashoka himself and augmented by others after him. Its intricate carvings include scenes of urban life, foreign visitors, animals, jataka tales, stories from the Buddha’s life, and much else. One can also see continuities with the art of the Harappans. The stupa’s beautiful art includes this dangling yakshi, with the same sort of mekhala belt around her hips that we saw in the Harappan female figurines. Many exquisite yakshi sculptures have been found, which seem to amplify the Harappan taste for curvaceous bodies. We see tantalising continuities in jewellery, ornaments, and headdresses. The origins of these voluptuous yakshis lay neither in Vedic Brahminism nor in Buddhism, but in folk religious cultures outside them both. In fact, they were mostly rooted in non-Aryan belief systems. They represented popular goddesses of prosperity and fertility, such as Sri. Including such iconography on their religious monuments was a clever move. It made this new thing called Buddhism more palatable to the wider public.

Ashoka’s edicts on rock surfaces and sandstone pillars appeared throughout his empire. They were written in various Prakrits, and in Greek and Aramaic in the northwest. His officials probably read it aloud to a public that was still largely illiterate. One fine specimen is the lion capital at Sarnath, now the national emblem of the Republic of India. I also love this head of a suave looking gent from the 3rd century BCE. I like his sardonic smile. Who knows, perhaps he belonged to a society of sceptics that may have inspired the Greeks.

Finally, this folk goddess figurine from the Mauryan era reminds us of Harappan figurines like this one, with their ornate headdresses and ornaments. This clearly shows continuities in artistic tastes and conventions.

After the Mauryas

After Ashoka, the Mauryan empire would fragment and shrink. The last of the Mauryas was murdered by an overzealous Brahmin named Pushyamitra, who was a Mauryan official. He then founded the Shunga Empire in Pataliputra. Scholars think that this was an orthodox Brahminical backlash to Mauryan rule. Pushyamitra hated Mauryan support for Buddhism, and he even persecuted Buddhists.

A fair bit of art from this period has survived. The eastern edges of the Shunga empire, where Indo-Aryan influence was weak, have left behind some remarkable art. Here are some examples from Bengal. They very much reveal a non-Aryan aesthetic of the human body and sexuality. We can see a new kind of realism and emotion in this art, and women are prominent in it. The subject matter is often secular, containing scenes from ordinary life. Amorous couples have started appearing on terracotta plaques. There is also some erotica from this period in Bengal that significantly predates later developments in other parts of India. At this stage, it’s not yet on the walls of temples or stupas but on small personal terracotta objects, such as plaques, vases, and other decorative art. These centuries also saw the maturation of the Jataka tales and the fables of the Panchatantra, Patanjali’s yoga sutras, Tamil Sangam poetry, and more.

In the northwest, the Indo-Greek states were replaced by the Sakas and then the Kushans, one of whose kings was the famous Kanishka. The sculpture of the Gandhara school, with its sublime Indo-Greek aesthetic, is perhaps the most visible legacy of this period. By then the Mathura school of art was also producing beautiful statues in its typical red sandstone. Some of the architectural marvels from these centuries include the Bharhut and Amravati stupas, and the many elaborate rock-cut caves of the Buddhists and Jains. On the social front, ideas of ritual purity and pollution, high and low caste, are evident in the literature of the period. The still evolving epics also embrace them. Many texts speak of despised jatis like chandalas, and of others involved in physical work like cleaning, basket making, hunting, fishing, and so on. A new hierarchical social order is well underway.

In the next episode, I’ll turn my attention to south India. After the Mauryas, the big political entity there was the Satavahana Empire, alongside many smaller kingdoms. I’ll focus on the remarkable Ikshvaku kingdom and its capital city of Vijayapuri, located near Nagarjunakonda in Andhra Pradesh. See you next time!

Bibliography/further readings

- Allen, Charles, Ashoka: The Search for India’s Lost Emperor, Abacus, 2013

- Dahlaquist, Allan, Megasthenes and Indian Religion: A Study in Motives and Types, Motilal Banarsidass, 1996

- Evans, James, The History and Practice of Ancient Astronomy, OUP, 1998

- Keay, John, India: A History, Harper Collins Publishers, 2000

- Kulke, Hermann, Dietmar Rothermund, A History of India, Psychology Press, 2004

- McCrindle, J.W. (Translator), ‘Ancient India as Described by Megasthenes and Arrian: A Translation of Fragments of Indika of Megasthenes Collected by Dr. Schwanbeck, and of the First Part of Indika of Arrian’, Trubner and Co., 1877

- Muhlberger, Steve, ‘Democracy in Ancient India,’ 1988

- Olivelle, Patrick and M. McClish (Eds.), The Arthaśāstra: Selections from the Classic Indian Work on Statecraft, Hackett Publishing, 2012

- Sen, Amartya, The Argumentative Indian, Penguin, 2006

- Sen, Sudipta, Ganga: The Many Pasts of a River, Gurgaon, Viking, 2019

- Singh, Upinder, Ancient India: Culture of Contradictions, Aleph Book Company, 2021

- Singh, Upinder, Political Violence in Ancient India, Harvard University Press, 2017

- Thapar, Romila, Early India, Penguin Books, 2002

- Thapar, Romila, The Past as Present, Aleph Book Company, 2013

Leave a comment