The answer to the miseries of modernity isn’t to reject modernity — it’s to demand more of it.

New issue coming soon. Subscribe to our print edition today.

The Essential Guide to Jacobin

The Verdict on Henry Kissinger

RENÉ ROJAS BHASKAR SUNKARA JONAH WALTERS

Cori Bush: Why I’m Calling for a Cease-Fire in Gaza

There Was an Iron Wall in Gaza

When I was an undergraduate, modernity was everything we were taught to despise: totalizing, technocratic, rationalizing. It was the impersonal force that organized Africa into colonies and the motor behind the mechanized doom of fascism. As Theodor Adorno wrote, the logic of modernity ends in a death camp, or the mathematics of a strategic bombing campaign — in human beings becoming abstract numbers in a computerized death count.

Marxism itself is not immune from these kinds of critiques. As writers in the Frankfurt School maintained, our problem in advanced industrial societies is to be treated as an instrument, a thing — a problem as deeply felt in the Soviet Union as the United States. As Russell Means, one of the founders of the American Indian Movement, commented, Marxism is just another word for rendering people into resources.

Indeed, much of the justification for modernity by even Marxist economists is that for all its brutality, modernity makes production more efficient and thus affords us the possibility of plenty. Yet, these critics charge, the processes that make us free enslave us as inputs to the very machines that were supposed to free us. One person’s utopia of material plenty is dependent upon another’s swing shift at the factory.

One might think Marshall Berman would have good reason to distrust the modern: growing up in the Bronx, his neighborhood was decimated in what was one of the most violent processes of urban destruction in the twentieth century. Politely referred to as “urban renewal,” a process of urban modernization that integrated dense neighborhoods within the expanding US highway system, it often targeted low-income neighborhoods, wiping out vibrant ethnic cultures, decimating small business districts, and breaking up support networks and communities — all in the name of that most modern ideal, Progress.

The Bronx went from being a multi-ethnic neighborhood of solid working- and middle-class apartment complexes to one of the poorest neighborhoods in the United States. Berman describes the destruction of his old neighborhood in haunting detail:

The foreground was broken. Now many tenements and apartment houses are cracked, burnt, split apart, caved in. Whole blocks have vanished or disintegrated into wreckage and debris. On other blocks, only a single house is left, with rubble all around . . . and if you examine its curves and details, you can often see that once, maybe not long ago, this sole survivor was once quite grand.

Berman even invented a word for what the process of urban renewal did to his city: urbicide, the planned murder of a city.

And yet in one of Berman’s most elegant essays in this posthumously published collection, Modernism in the Streets: A Life and Times in Essays, edited by David Marcus and Shellie Sclan, he writes a tribute to the Faustian grandeur of the man who did this to his beloved Bronx, Robert Moses — the man Robert Fitch memorably accused of “assassinating” New York.

To understand Berman’s seemingly paradoxical view of the processes of modernity — how he could write perhaps the most generous tribute I’ve read to the man who quite literally drove a tractor through his beloved Bronx — we have to remember that Berman was a dialectical thinker, one who invited us to understand the warp and weft of modernity through a Marxian lens.

Marxism for Grownups

We can start with his own re-reading of the Communist Manifesto, perhaps the most often read, and misunderstood, pamphlet of all time. Too often, Marxism is read much like one would read a pulp detective novel. There are the good guys (workers) and the bad guys (capitalism), and it all wraps up rather neatly for a group picture and a smoke at the end, after an epic shootout by gunslingers on either side. This binary, comic-book view of capitalism and communism has been operative for its supporters and detractors alike.

Yet Berman has another way of reading the Manifesto, one he charges is only for “grown-ups” who can handle the nuance. He invites us to read Marx’s most polemic text as a process of open-ended contradictions, one that has no resolution outside its own dizzying acts of destruction.

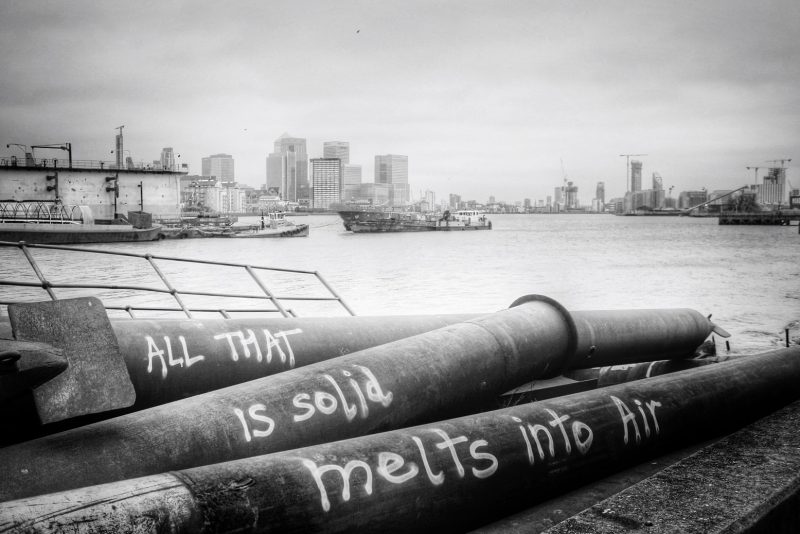

Berman quotes the Manifesto‘s passage from which he takes the title of his most famous book, All that is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity:

The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionizing the instruments of production, and there by the relations of production, and with them the whole relations of society . . . Constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses, his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.

There is the sense of being caught up in something “magical and uncanny,” a process that is both terrifying and exhilarating. It’s not enough to simply say that Marx appreciates the productive force of capitalism; he appreciates its destructive force as well, the sublime terror of a new order brought into the world, an order that is itself unstable, promethean, in a constant process of renewal and destruction. “All that is solid melts into air” is both a warning but also a promise.

What is remarkable about Berman is not just his perception of Marx as a dialectical thinker. For Marx, the crucial difference between capitalism and feudalism is not just that they both exploit people and resources, but how this exploitation takes place.

Capitalism is not only unique insofar as it hides its exploitation through the veneer of equal exchange between workers and owners. Capitalists must also constantly revolutionize production through time, space, and technology to produce more value: automating factories, moving the colossus of production around the world, transforming food into giant factories in the field, revolutionizing the human body through pharmacology.

This experience, however, cannot just be expressed through surplus value equations or graphs depicting the rate of exploitation. At some point, as Hegel famously said, quantity becomes quality: capitalism’s constant revolution of the means of production and circulation produces a radical new subjectivity, a new way of seeing, a new kind of person.

Marx, for Berman, was not only modern, but a modernist, someone who self-reflexively experienced and wrote about the subjective world of industrial capitalism.

Berman recognized this even at the level of Marx’s sentences: Marx “was the first to invent a prose style” that brought the “perilous creativity” — even brutal creativity — of capitalism to life. As Berman points out, the sentences in the Manifesto are relentlessly dialectic, they lunge and fall back on themselves before leaping to a new wonder — and terror — produced by the rapacious will of the nineteenth-century bourgeoisie.

For Berman, to read the Manifesto is not only to understand capitalism’s destructive allure, but to feel it as well.

Caught Up in the Flux

There is a primal scene in All That is Solid that brings to life the new experience of feeling modern. As the prototype of the urban renewal that smashed through the Bronx, architect Baron Haussmann obliterated the small medieval neighborhoods of Paris into the grand, sensual nineteenth-century boulevards we see today in postcards. This destruction of the old Paris was also the opening of new visual and public spaces — old neighborhoods were literally torn open, and pedestrians could walk on café-lined streets through the entire city (as could troops and artillery should there be another communard insurrection).

Berman meditates on the meaning of these new, modern streets and their social spaces of cafes and restaurants through the Baudelaire poem, “The Eyes of the Poor,” in which a middle-class couple is observed eating a luxurious meal by a beggar, perhaps one recently displaced by Haussmann’s “modernization.”

“What did the boulevards do to the people who came to fill them?” Berman asks. “Caught in up in its immense and endless flux,” the boulevard becomes a place to see and be seen, a place of “amorous display,” where one showed oneself and one’s fantasy of life to others to a new modern “family of eyes.”

This play of spectacle and fantasy, where the flaneur meets the window display, cannot exist long without the repressed reality creaking through. The couple in Baudelaire’s poem, having gone to the café to experience the luminous pleasure of grand boulevard, are confronted by a destitute father and his two children who gaze into the café to marvel at the sumptuous food and ambience. The woman is horrified and wants to ask the maître’d to force them away from the window. The man is moved by the family’s rags, while also disgusted by both his romantic partner, and the feast they share between the two of them.

This brief exchange, for Berman, is the both the promise and the unique subjectivity of the modern.

Not only is there the moment of self-reflection by the man, where he is forced to see himself through the eyes of another; there are also the eyes of the poor, separated only by a slim pane of glass from the food and comforts of a good life. And despite the man’s liberal sentimentality and the woman’s right-wing barbarism, Berman sees this interaction as the shock, disequilibrium, and promise of both the art and architecture of modernism, bringing both pleasure and dis-ease of modern life into contact.

Returning to the view from the Third Avenue Bridge, Berman relates how, driving through the Bronx in the late 1970s, one sees simultaneously the “magical aura” of Manhattan and the burning hellscape on the other side. This twin view, this double vision, this forward and backwards motion through space and time is the strange vitality of modernity and its unique historical experience.

From the Ruins, Yet Not Ruined

As part of Berman’s insistence that the violent shocks of modernity produce new, radical subjectivities, he devotes a major portion of the book to chronicling how hip-hop and street art emerged out of the ashes of a devastated Bronx. “Because of its misery and anguish — the Bronx became more culturally creative in death than in life,” Berman writes.

Starting with the “bold and adventurous visual language” of subway and ruin graffiti, Berman makes the argument that graffiti throw-ups and blockbusters are not just visual litter, but attempts to communicate with the wider city — which in turn sparked a costly, destructive, and even deadly conflict with city agencies that criminalized such public art.

The conflict over the public space that graffiti provoked for Berman was much like the Baudelaire poem, in which the site and presence of the poor, suddenly erupting into the streets, creates a panic for the bourgeois order: their own processes of development have summoned forth voices that they cannot control and do not understand.

Moving from graffiti to hip-hop, Berman muses on the most famous hip-hop song to emerge from 1980’s Bronx, Grandmaster Flash’s “The Message”:

What was “the message”? Maybe, We can be home in the middle of the end of the world. Or maybe, We come from ruins, but we are not ruined. The meta-message is something like this: Not only social disintegration, but even existential desperation, can be sources of life and creative energy.

The view from the bridge, while disorienting and perhaps chaotic, is also the starting point for new possibilities, new ways of seeing. “Modernism in the streets” is not a claim about formal style or literary genre, but a recognition of the way the urban maelstrom enlarges the sensorium, opens doors for new perceptions, and reorganizes mental life.

More, Always More Modernity

Three of Berman’s most touching essays in the collection are about twentieth-century Jewish intellectuals: Walter Benjamin, Georg Lukács, and Franz Kafka, all of whom lived through and died of the violent contradictions of modernity.

The longest and most illuminating of the essays is on the life of Lukács, the Hungarian communist most famous for identifying reification as the central subjective experience of life under capitalism. For Lukács, capitalism does not merely exploit our labor but also fragments our subjectivity and turns the processes of life into inanimate objects: our labor, our social reproduction, our imaginations.

Factories and bureaucratic offices are not merely centers of production and reproduction, but ideological apparatuses that transform us into things. Indeed, “reificiation” is a poor translation from the German for “process by which a human being is transformed into a thing.”

The experience of life under capitalism is one of passivity, to be a mechanical part for a mechanical system. And yet, unlike those who would wish to make the machines simply stop, Lukács believed that the role of the working class is to be both objects and subjects of capitalism, to understand the way they’ve been reified but also to develop their own intellectual and emotional standpoint: what we refer to as “class consciousness.”

For Lukács, the vehicle for this new form of subjectivity was to be the revolutionary party, one that could transform modern life from the factory to the apartment complex to the field: “the economy,” Berman explains, “won’t be a machine running on its own momentum toward its own goals, but a structure of concrete decisions that men and women make freely about how they want to live and fulfill their needs.” The answer for the problems of modernity, for Lukács, was a radical new form of modernity, the revolutionary party and the workers’ council.

Yet like many other of Berman’s heroes of modernity, Lukács spent a great deal of his life in prison, first in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and then in the prisons of Stalinist Hungary, after the brief-lived 1956 revolution. Lukács would come to recant much of his youthful work and go on to write literary criticism that seemed to advance Soviet orthodoxy, denouncing modernism as the excesses of a decadent bourgeoisie and Kafka as “mental abnormality.”

Yet as with much of Berman’s writing, he is always ready to offer any subject a second act, or even a third or fourth. Lukács denounces his earlier denunciation: “I was wrong,” he was reported to have said from Dracula’s castle, which the Soviet authorities transformed into a prison. “Kafka was a realist after all.”

Berman’s final assessment of Lukács is much like his assessment of modernity itself: “it can offer no final epiphany, only more layers under layers and wheels within wheels, more … enticing and infuriating blend of blindness and insight.” What is heroic about Lukács is much like what is heroic in modernity: not in some final moral gesture or intellectual consistency, but rather in the “demands he made on modern art, on modern politics, on the whole of modern life” that it conform to our grandest desires and most utopian dreams.

That Lukács ended as a victim of the modern nightmare of Stalinism is no more ironic than Walter Benjamin ending as the victim of fascism. Modernity is an open-ended process that ends badly usually only when someone declares it complete.

Race and the Modern

Berman’s optimistic and open-ended processes of modernity can, however, sometimes elide the racial structures through which the modern world came into being. In his essay on the infamous 1927 film The Jazz Singer, Berman celebrates the Jewish “jazz singer’s” use of blackface as part of modern self-making.

Berman is absolutely correct to point out that The Jazz Singer is an important text on the meaning of modernity. Jackie Rabinowitz, the teenage son of an immigrant ultraorthodox cantor, runs off to be a jazz singer after his authoritarian father beats him for singing “raggy time songs,” in a Hester Street saloon.

Rabinowitz drops his Jewish last name, his father’s beard, and, dressed in fashionable modern suits, swivels his hips and sings for cabaret audiences while eagerly trying to make his “break.” His final act, and identity crisis, occurs when “blacking up” to perform “My Mammy” at the invitation of his goyishe girlfriend Mary Dale, while his father lay dying of grief the night before Yom Kippur.

Will he sing Jewish songs for his dying father, or go on stage? Will he return to his father’s shtetl ways or embrace his new modern subjectivity as a man with no past, no essential identity, who can be black one minute and white another?

Weighing the many fragments of his identity, Berman comments that this is both the promise and predicament of modern self-hood: only by “putting on someone’s face” can he recognize his own.

Blackface, for Berman, is part of the ongoing romance of marginality, from which Jews produced a mass culture of multiethnic liberalism. Modernity, in this story, frees Robin/Rabinowitz from his ghetto and shtetl past, allows him to make a truly universal culture that allows for the inclusion of everyone.

Yet modernity has never been a universal story, from the gunboats of Western imperialism to the plantations of the American South. Blackface minstrelsy is only part of this cultural tale. While Robin/Rabinowitz becomes a modern person, he can only do so in the anti-immigrant, antiSemitic cauldron of 1920s America by defining his modernity against imagined primitivism of blackness.

By donning blackface, Robin/Rabinowitz declares that he can become anything — precisely because he can no longer be defined as black. Whiteness is literally and figuratively one face of the modern world, one that allows entrance to some while denying others, one that believes egalitarianism and freedom is something that can only be preserved by restricting it.

While Berman is aware that African Americans were being lynched while Robin/Rabinowitz performs “My Mammy,” that these two acts may be correlated if not causally linked does not make into his essay. Rather than see Jolson’s performance as part of the “liquidity” of modern self-formation and the beginnings of a multicultural politics, the reactionary and assimilationist politics of The Jazz Singer argues for a far bleaker scenario: that modernity can only be secured by constructing an Other as a primitive.

The Prison or the Grand Boulevard

Berman’s dubious reading of The Jazz Singer does not however, dampen my overall enthusiasm for the collection of essays. As Berman himself would say, the response to the crisis of modernity is more modernity.

The problem with The Jazz Singer is not only that it’s racist; its modernity is far too narrow. Rather than the urban maelstrom of 1980s Times Square, one of Berman’s favorite subjects, the modernity embraced by Robin/Rabinowitz is sanitized, soft-jazz versions of black music.

Indeed, it is the broadness and scale of Berman’s vision of modernity that is the power of this collection. He shows how the fate of a radical Jewish intellectual from the Bronx is tied with the early hip-hop of Grandmaster Flash, and both are tied to the older history of urban uprisings and displacements of revolutionary France, the Bolshevik Revolution, and other “shouts in the street” from which Berman takes his counter-culture of modernism. Robin/Rabinowitz would have done better to have just taken the next train to Harlem rather than perform for the anodyne stage of Broadway. Berman’s impulses of solidarity are correct, but Robin/Rabinowitz is no Jacobin, black or white.

W. E. B. Du Bois said as much in his essay Souls of White Folk, that among all ideas of the modern world, race has had the most dreaded material continuity. And yet as C. L. R. James reminds us, the slaves of San Domingue were also the first modern proletariat and Toussaint L’Ouverture the first modern revolutionary, who saw his world in much the same way Berman understands the ruins of his Bronx: there is no way out but through the awful contradictions of the modern world. Grandmaster Flash is one of the important voices of a self-fashioning, creative urban modernity, as were the politics and stylistics of the Black Panther Party and their Harlem Renaissance pre-cursor, the African Blood Brotherhood.

It is a lesson for which we are in dire need today. It is continually heartbreaking that Berman is not alive to offer commentary on the Donald Trump era. In response to the miseries brought by the bourgeois modernity of a globalized elite, the answer increasingly comes in shape of demagogues who would drag us back into the past, to the isolating languages of tribe and race; the modernity of a high-tech prison or a giant border wall.

Trump, Marine Le Pen of France, Geert Wilders of the Netherlands, and other far-right politicians offer solutions to the modern world designed precisely to stop the chance encounters such as Baudelaire describes in Paris, or Berman tracks with the rise of hip-hop out of the ashes of the Bronx. They promise us all the ruin of modernity with none of the possibility.

If Berman were still alive today, his response to Trump’s “American carnage” would not be an insistence that “America is Already Great,” but rather that the solution to America’s miseries can be found literally in the gears of the crisis.

Automation could provide the plenty to give us all lives of leisure; the climate crisis could push us to live in denser, more populous cities powered by renewable energy; the breakdown of the family could lead to a more expansive notion of child care and sexuality; the breakdown of borders could lead to new solidarities across the globe. Berman’s interest, perhaps even nostalgia, for modernism is the desire to think big, to imagine bold solutions for economic and political crises.

Nearly all the lights of modernist literature, whether fascists such as Ezra Pound and Wyndham Lewis or socialists such as Richard Wright and Muriel Rukeyser, felt that a grand transformation of society was not just possible, but that it was the only inevitable solution for the decay of liberalism. Whether or not we have modernist authors on the Left who are willing to lead the way, the crisis is the same: we will have modernism or barbarism.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

CONTRIBUTORS

Benjamin Balthaser is associate professor of multi-ethnic US literature at Indiana University, South Bend. He is the author of Anti-Imperialist Modernism and Dedication.

Karl Marx: Flawed, Manic, and One of Us

A new book brings to life Marx’s formative years in London, filtered through the prism of magical realism.

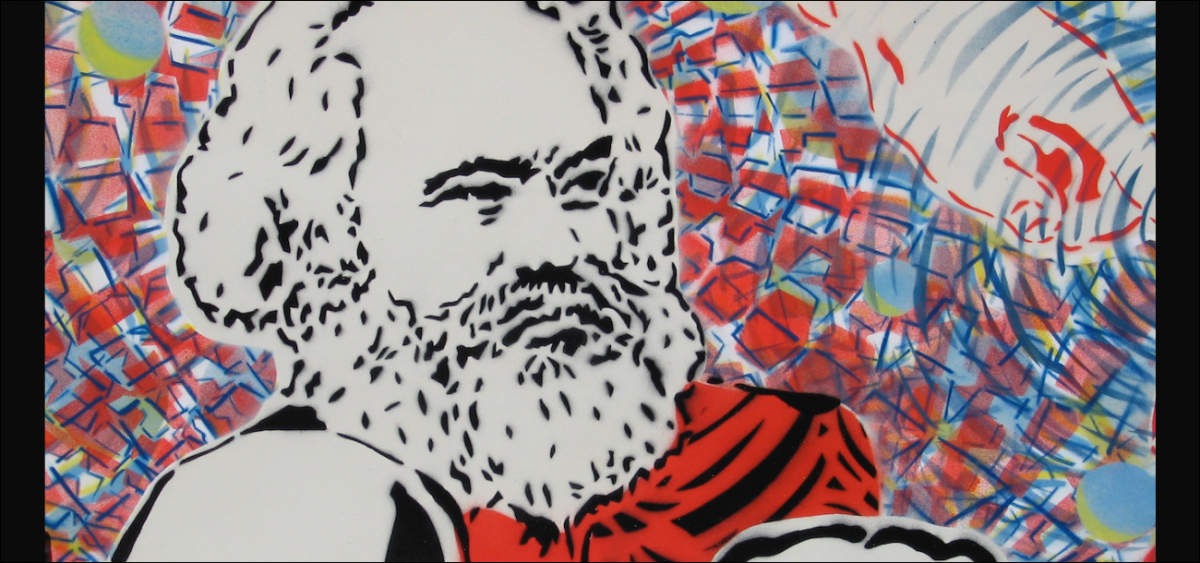

Jason Barker’s Marx Returns vividly reimagines Marx’s London years, dwelling primarily on the personal, political, and financial turmoil experienced by the Marx family during the 1850s. Credit: rocor/Flickr

BOOKS27/SEP/2018

“Do you not exist? Do you feel like a machine? Does your life count for a mere commodity and nothing else besides? There in a nutshell, gentlemen, is what my ‘philosophy’ amounts to. And this is what we must all struggle against.”

When Karl Marx arrived in London in 1849, together with his wife Jenny and their three children, he was a thirty-one-year-old refugee. Already exiled from Paris, Brussels, and Cologne, Marx was a largely obscure figure. The Marx family planned for their stay in London to be brief, expecting that the revolutionary wave sweeping the European continent would go on. Instead, the revolutions were suppressed and England became Marx’s homeland for the rest of his life.

The Marxs’ move to London placed them in the financial capital of the world, and close to Manchester, its industrial capital. Marx thus ended up living out his remaining years at the very heart of the system that he spent his life struggling to theorise and overthrow. For better or worse, the understanding of capitalism captured in his mature thought was entwined with the history and culture of his adopted land, so that it would not be unreasonable to call Capital a thoroughly English work, in its subject matter, sources, and the tradition of political economy it deeply engaged with, if not in original language.

Marx Returns

Jason Barker

Zero Books, 2018

Jason Barker’s Marx Returns vividly reimagines Marx’s London years, dwelling primarily on the personal, political, and financial turmoil experienced by the Marx family during the 1850s, what was surely their most difficult decade. Although Barker draws on events from Marx’s life, the book is decidedly not a biography, which would have placed it in a suddenly crowded field, alongside recent contributions by Mary Gabriel (Love and Capital, 2011), Jonathan Sperber (Karl Marx: A Nineteenth Century Life, 2013), Gareth Stedman-Jones (Karl Marx: Greatness and Illusion, 2016), and Sven-Eric Liedman (Karl Marx: A World to Win, 2018).

Instead, as Barker makes clear, Marx Returns is a work of historical fiction. The book creatively weaves together real historical events; imaginative flights of fancy from Marx’s point of view, meditating on the nature of capital, mathematics, and ontology; and an uptempo narrative that is at heart a familial drama about the experience of exile in the nineteenth century. Together, these elements combine to create a whimsical book that tries to put a new spin on Marx’s life for those already familiar with it, while at the same time acting as a general introduction to its subject matter for those uninitiated, with mixed results.

Marx Returns arrives at what is now the post-1989 peak of the revival of interest in Marx and communism, which began roughly ten years ago, in the wake of the financial crisis (Barker himself is the writer, director, and co-producer of the 2011 documentary Marx Reloaded). Despite this, Barker does not assume any prior knowledge of Marx’s biography or writings from the reader; sparse endnotes explain the references to Hegel, Bakunin, and the Paris Commune. As such, we can easily imagine someone coming to Marx Returns after first seeing Raoul Peck’s recent The Young Karl Marx, especially since the two works almost seamlessly align in their chronology (and I confess to visualizing that film’s lead actors when reading this book).

But whereas The Young Karl Marx is a work that aspires to realism, Marx Returns is entirely defined by the wildly subjective mental state of Karl and, to a far lesser extent, Jenny. All the characters, from the central to the peripheral, are larger than life, fictionalized versions of the historical personages, and their exaggerated personalities naturally lend themselves to many humorous scenes.

Engels figures prominently as a dapper and somewhat absent-minded but loyal friend. Bakunin makes a couple of notable appearances, none more memorable than when he tries to recruit Marx into his plot to lead an army of twenty Ukrainian peasants on a campaign to liberate the Russian Empire. And Lenchen, the Marxs’ headstrong and cynical housemaid, and in many ways the most grounded member of the household, perpetually berates Karl for his inability to provide for the family.

Yet these characters remain largely secondary to the battle inside Marx’s own head, which takes centre stage in the narrative. Barker’s Marx is himself something of a mad scientist. More obsessed with calculus than with either political economy or history, he is perpetually manic, furiously scrawling sentences and paragraphs almost immediately indecipherable to himself, pawning off the family’s furniture, the children’s toys, and eventually, the literal shirt off his back.

What he is struggling to bring into the world, as he tells another character, is “a systematic work that penetrates to the very core of the bourgeois society, that grasps the real movement, the development of the social forces and relations of production as a finite mode in the universal scheme of things.” This work eventually materialises in the form of the first volume of Capital, but, as the novel suggests, at considerable expense to Marx’s sanity, personal relationships, and political goals — especially once it becomes clear that his fellow comrades in exile have little patience for the science behind Marx’s project.

Not surprisingly, London prominently figures as a backdrop to the story, as a living, breathing city that is teeming with the groans of the paupers, shopkeepers, landlords, and workers that Marx encounters daily. Most remain nameless, mere shadows for Marx’s perpetually agitated mental state to play off against. Capital repeatedly appears in the metaphor of an omnipresent, accelerating train, an agent of creative destruction that seeks to dominate nature and revolutionise the entire social fabric, from politics to the family to love. Yet it also brings its Other, at least in Marx’s imagination. In one such vision, the slums of Lambeth and the East End give life to the “wild and dysfunctional breed of living-dead labour that refused to stop working, the rebel power with nothing else in mind other than the fabrication of the tools for the takeover of society.” Naturally, this proletarian Leviathan, created by capital but now beyond its control, marches forward to set fire to Westminster Palace.

Barker peppers some of Marx’s most famous quotes throughout the text, anachronistically and in new contexts. “All that is solid melts into air” comes after seeing a rumbling steam engine in London’s downtrodden, primordial Lambeth Marsh. The idyllic vision of hunting in the morning, fishing in the afternoon, and playing chess as one pleases is now uttered by Jenny.

Occasionally, this playful drifting from the historical record, while meant to give a new urgency to Marx’s ideas, comes off as heavy handed, as when “religion is the opium of the people” is uttered by a priest. Nevertheless, it contributes to the story’s dreamlike character, an overwhelming magical realist haze in which its characters are perpetually straining to make sense of the rapidly changing world around them and to communicate their inner world to others. More often than not, they fail, giving a meandering quality to the story that tends toward impressionistic sketches rather than a clear narrative arc.

To its credit, rather than valorizing its hero, Marx Returns presents its protagonist as a deeply flawed character. Barker’s Marx is neck deep in debt, always mentally exhausted, impatient with his comrades, unfaithful to his wife, often neglectful of his children, and perpetually tormented by his boils. Barker also hints at the uneasy relationship between the demands of the revolutionary horizon and the uncompensated domestic labor that is borne by Jenny and especially Lenchen. “Love sharing and mutual need were incalculable. How could Marx ever hope to calculate Helene’s wages?” Barker has Marx wondering at one point. Yet instead of pursuing this paradox to a conclusion — that his obsession with calculus and infinity is, at best, tangential to the practice of revolutionary politics as a shared, and gendered, human experience — Barker’s Marx simply puts this question aside, not to pick it up again.

Ironically, these character flaws also make Marx come across, if not entirely as a sympathetic figure, then at least as our contemporary. That is, as someone suffering from the same pressures, neuroses, and anxieties that many experience today, despite capitalism having promised to alleviate them through the near unlimited choice of commodities and nonstop entertainment. Capitalism is the cultivation of bourgeois desire, we are told at one point, in a remark even more accurate in the twenty-first century than the nineteenth. Karl and Jenny are themselves on the margins of the nineteenth-century bourgeois experience, people of education and “culture” who are painfully aware of their downward mobility at a time when the society they were brought up in is mutating before their eyes.

Marx Returns ends on an uplifting note, with the news of the Paris Commune reaching an exuberant and ageing Marx in London, who is by then beginning to gain some attention and renown. The choice to end the book with a call for the people of Paris to defend themselves against the pending assault from the national army, just days prior to the massacre of thirty thousand communards, is telling. The brutal suppression of the first government of the working class in European history anticipated the horrors and destruction of the twentieth century. Yet by invoking the Commune as a historic Event, the novel presents it as a symbol of an unfinished political project — one that links Marx to subsequent working-class militancy up through the present, thereby also “returning” him to us as an interlocutor.

At one point, a despairing Marx thinks that “instead of being a theorist of the here and now, he was destined to end up as a ‘posthumous’ author, dug up like the Great Fossil Lizard for future generations and taken for a quaint observer of futures long since past.” Yet today Marx is being read not as an antiquarian thinker, but with the fresh eyes of a new generation of activists, scholars, and citizens who see him as an enduring analyst of capitalism and its crises.

The 1990s and 2000s assured us that we could not afford to believe in the immanence and historical necessity of communism. In contrast, the present decade is suggesting that capitalism and the relations of domination that it generates are not a viable long-term solution for human flourishing and the preservation of our planet.

Perhaps there is time yet to stop the headlong rush of the train of capital toward the edge of the precipice. Or perhaps later civilisations will unearth and display the artefacts of our long-gone one, marvelling at our unwitting demise, as the Victorians of Marx’s time did when they resurrected the extinct “Mesozoic lizards” among the primeval smokestacks and machinery of nineteenth-century London.

Rafael Khachaturian is a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Center for the Study of Democracy at the University of Pennsylvania.

This article was republished with permission from Jacobin. Read the original here.

1

Support The Wire

₹2400 once

The founding premise of The Wire is this: if good journalism is to survive and thrive, it can only do so by being both editorially and financially independent.This means relying principally on contributions from readers and concerned citizens who have no interest other than to sustain a space for quality journalism. For any query or help write to us at support@thewire.in

JUNE 18, 2018

All that Is Solid… Is Maybe Not So Solid: The Repercussions of a Translation

EDITOR’S NOTE

Let me preface by saying that my German is not good, so if I am way off here, I hope someone who is more fluent than I will set me right. But I’m writing this as a kind of follow-up on last week’s post about Karl Polanyi’s effect on historians. I’m not going to tie the two posts together too explicitly as yet, but I think you’ll see where they link up.

The other day I was writing about a book that made use of the famous phrase from The Communist Manifesto “all that is solid melts into air,” and I thought to look up the original German, which is “Alles Ständische und Stehende verdampft.”

It struck me immediately that the conventional translation of this line is a bit paltry. There is an obvious play here in “Ständische und Stehende.” What is being evoked is not “solidity,” but rather “standing,” as in social standing.[1] But that is not its only connotation: in German (as in English or Latin) “standing” is inflected with that other range of meanings related to “stand”—those that associate standing with stasis, with being stationary or even stagnant. (This overlap or confluence of meanings may be clearer in Latin: sto, stare, steti, status are the principle parts of the verb “to stand.”)

Well, perhaps you’ll say, so what? No one has ever accused me of an allergy to pedantry, but I think this is not just a case of the quibbles. On the contrary, the common (“All that is solid…”) translation has, I want to argue, produced a quite serious misunderstanding of Marx and Engels’s meaning among English speakers, and that misunderstanding has radiated out well beyond self-identified Marxists and shaped broader conceptions of how capitalism has changed society and how capitalist societies differ from pre-capitalist societies.

Think about the difference between saying that an object is solid and saying that it is standing. Solidity is related to density—its antonym is hollow—and it evokes (in my mind) a connotative register of stability and weight, of imperturbability. What is solid is durable, is unlikely—apart from some extreme and unusual force—to be destroyed or transformed. It is, if not permanent, at least very unlikely to change.

Now, what about “Ständische und Stehende?” Neither “standing” nor “stationary” have that same sense of permanence or durability; within either concept is the seed of change—“standing” posits a future change of posture, and “stationary” connotes a kind of precarious stagnation, easily disturbed into motion. “Standing” in the sense of a social order already imagines a shakeup: mutability is incorporated at a conceptual level. We use the phrase “status quo” precisely because the expectation of a subsequent change (or the knowledge of a prior change) is already baked into “status.”

Medieval or ancient societies that truly imagined their arrangement to be perpetual tended to use other words to signify the divisions of society: rank, order, degree. (Again, I’d like a specialist to verify my hunch here.) Chaucer tells us in the prologue to The Canterbury Tales that he is going to describe to us each pilgrim because he “thinketh it acordaunt to resoun, / To telle yow al the condicioun / Of ech of hem, so as it semed me, / And whiche they weren, and of what degree.”[2] “Condicioun” is their outward appearance, and even if it reflects their underlying “degree,” the latter is presumed to be immutable while the former is not.

That is not the presumption of Marx and Engels, however; in fact, they emphasize the fact that no system of social ranks or divisions is permanent (or solid) by pointing to prior arrangements: “In den früheren Epochen der Geschichte finden wir fast überall eine vollständige Gliederung der Gesellschaft in verschiedene Stände, eine mannigfaltige Abstufung der gesellschaftlichen Stellungen.” By using “Stand” and “Stellung,” but they underline the plasticity of these systems of gradations. Even more, they emphasize that humans have not had only one kind of social ordering before capitalism, but many.

Translating Marx and Engels’s passage as “All that is solid” makes the “melting” or “evaporating” caused by capitalism suggests something different: it suggests that what came before capitalism was—above all—not fluid. It was built well, it was stable. “All that is solid” produces a sentence and a reading of capitalism’s emergence that is much more dramatic. It takes a lot of energy to melt something solid, and things that are solid are not supposed to melt! (More on melting in a second.)

If, on the other hand, we were to translate the passage as “Every [social] standing and all that is stationary,” we still get a sense of tremendous transformation, but not necessarily something unexpected.

The previous sentence in the Manifesto supports this reading, I think: “Alle festen eingerosteten Verhältnisse mit ihrem Gefolge von altehrwürdigen Vorstellungen und Anschauungen werden aufgelöst…” “Fest” is “firm” or “solid,” but “eingerostet” is “rusty,” again emphasizing change and even stagnation. That is doubled in the lovely last part of the sentence: “alle neugebildeten veralten, ehe sie verknöchern können.” All that is novel expires even before it can ossify.

Now what about “melt?” “Verdampfen” isn’t “melt,” although “melt into air” is a rich phrase and much better. But here again we run into some trouble—of an admittedly technical nature—if we start the sentence with “All that is solid.” Verdampfen is “to evaporate,” which isn’t what the process of a solid melting into air is called. That is sublimation. Even allowing for some poetic license, there isn’t really any reason why Marx and Engels were thinking about the quite rare process of sublimation instead of the quite common process of evaporation—the transformation of a liquid into a gas.

What Marx and Engels are saying in this passage is that capitalism clarifies by continuously boiling away the palliatives of non-market values with which people try to soften or dilute the harsh judgments of the profit motive. Those values never have time to totally congeal before capitalism causes them to evaporate; they never solidify in the first place before they return to the air from which they condensed. Let us not talk about capitalism “eroding” or “melting” social solidarities, because those solidarities were never solid to begin with.

That is the only way, I think to read the sentence as a whole, which emphasizes not some sort of capitalist destruction of a permanent way of life, but of capitalism’s ability to dispel the myths that could interfere with its operation: “Alles Ständische und Stehende verdampft, alles Heilige wird entweiht, und die Menschen sind endlich gezwungen, ihre Lebensstellung, ihre gegenseitigen Beziehungen mit nüchternen Augen anzusehen.”

Typically, “alles Heilige wird entweiht” is translated as “all that is holy is profaned,” but it takes a weird reading of Marx and Engels to imagine them unsettled by the desecration of “holy” things. A better reading might be “all that is holy is deconsecrated” or even “disenchanted.” “Profaned” means “defiled” and carries a sense of violation which seems wholly out of character. But “deconsecrated/disenchanted” accords with the final part of the sentence, which tells us that capitalism forces us to confront things as they really are, forces us to face each other with nothing between us but capitalism itself.

That is, of course, not something they endorse, but it is inaccurate to detect in this sentence a wistfulness for the credulous mist that capitalism is dispelling. Yet so many historians—guided by the conventional translation—have used it as a kind of lament for the world of social solidarity, “the world we have lost” in Peter Laslett’s phrase—the moral economy, the pre-capitalist Gemeinschaft. It requires a misreading of the broader context of the phrase to get there, but it starts with “All that is solid.”

NOTES

[1] I later found that Richard Evans’s LRB review of Jonathan Sperber’s Marx biography makes this point: the review is behind a paywall, but a letter in the LRB expands on Evans here.

[2] Interestingly, “degree”—like “standing”—has its root in a Latin word related to the foot: gradus, meaning either pace or step. But the meaning it carries has a great deal more to do with “step” as in a part of a staircase than it does with walking. However, it is not surprising that a synonym for one’s social standing or one’s degree is also one’s “social footing.”

TAGS: 19TH CENTURY, CAPITALISM, CLASS/LABOR, FRIEDRICH ENGELS, KARL MARX, MARXISM, MODERNITY, THEORY, TRANSLATION

PREVIOUS POST

NEXT POST

Three Mostly Bad Pitches for Intellectual Historians to Think About

The Society for U.S. Intellectual History is a nonpartisan educational organization. The opinions expressed on the blog are strictly those of the individual writers and do not represent those of the Society or of the writers’ employers.

All text (including posts, pages, and comments) posted on this blog on or after August 7, 2012, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This blog is © 2007-2022 Society for U.S. Intellectual History.

Categories

Select Category Book Reviews Ideas Member News Modern Intellectual History Prizes and Awards Programs and Resources S-USIH Conference

Authors

Select Author Andrew Hartman Andrew Klumpp Andrew Seal Anthony Chaney Audrey Wu Clark Ben Alpers Benjamin Park Diane Mikho Emily Conroy-Krutz Eran Zelnik Holly Genovese Katherine Jewell Kevin Schultz Kurt Newman Kyle Larkin L.D. Burnett Mark Edwards Matthew Linton Michael J. Kramer Pete Kuryla Ray Haberski Ray Haberski Rebecca Brenner Graham Richard Candida Smith Robert Greene II Robin Marie Averbeck Sara Georgini Sarah Bridger Tim Lacy Young Chang

15 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

ANDY SEALThanks to Bill Fine, I was able to read the passage I mentioned in note 1 above from the Richard Evans review of Jonathan Sperber’s Marx biography. It turns out that my interpretation of the original passage is quite close to Sperber’s, which can be read here.

LOUISAndy,

An interesting post.Regrettably can’t comment on the strictly linguistic issues as my German is basically non-existent, but I’d like to make a couple of points. First, assuming that you’re right about the common translation not being a good one, it may be too late to dislodge it. It’s been repeated a lot, and Marshall Berman’s 1982 book taking the “all solid” phrase as its title is fairly well known.Second, you suggest that the “all solid” translation has misled commenters and readers into thinking that Marx and Engels were expressing wistfulness about “the world we have lost.” But has the translation actually misled people in this way? To put it perhaps too bluntly, can anyone with even a dim memory of having read The Communist Manifesto in school possibly think that Marx and Engels were nostalgic about the vanished pre-capitalist world? Doesn’t the Manifesto, in some passage or other, praise capitalism and bourgeois society for having swept away what Marx refers to as “medieval rubbish”? (Or is that in The 18th Brumaire or somewhere else?)Now it’s true that some Marxists (or Marxian-influenced) writers, such as E.P. Thompson, do wax eloquent about the moral economy of a pre-capitalist (or nascently capitalist) society in which the notion of a “just price” can be found (see e.g. Thompson’s classic article “The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century”). But as for Marx and Engels themselves, my impression is that they were quite uninterested in singing the virtues of pre-capitalist societies (though they may do so on rare occasion), whether those pre-capitalist values are seen as solid and permanent, or, as you put, “never solid to begin with.”If I were interested in finding out what it was like to be a peasant or artisan or town-dweller or vagabond or monk or nun or whatever in a particular part of Europe in the high Middle Ages (say, circa 1200 or so), and specifically what kinds of economic and/or social arrangements governed one’s existence, and whether they seemed permanent and fixed by a divinely ordained dispensation or open to some kind of challenge under certain circumstances, I would not turn to Marx and Engels for the answers. I just don’t think they’re very interested in those questions.Anyway, thank you for the post and look forward to the more explicit tie-in with the previous one.LOUISOn reflection, my comment above is probably a bit too broad-brush. (Part of the problem is that it’s been a long time since I read Marx.) The mature Marx presents himself as a scientist but passion and moral judgments come through anyway, sometimes sharpened by or reflected in his language and literary style, as R. P. Wolff among others points out (some of Wolff’s youtube lectures on Marx repay watching). Probably fair to say that Marx did deplore the separation of the artisan from his tools and control over his work entailed by the capitalist production process, and of course there are detailed descriptions in Capital of the oppressive conditions under which factory workers labored (setting up implicit contrasts with what came before). But there are also Marx’s fairly derogatory references to the peasantry. So a good deal may depend on which Marx work one happens to be reading, what mood one catches him in, and perhaps even which translation.

- REPLY TO LOUIS

ANDY SEALLouis,

That’s a really important correction. I should have been more precise: most historians who fetishize the “world we have lost” are not using Marx and Engels to ground their account of pre-capitalist society. What I see occurring is more of a generalized shift from “Marx as an analyst of capitalism” to “Marx as a prophet of modernity”–very much in the way Marshall Berman did (as you note in your comment). It’s not so much “pre-capitalist” society that they lament the loss of as it is the erosion of the face-to-face communities under the wheels of modernity and “the market.” “All that is solid melts into air” does double duty, there: it’s a statement about capitalism and a sentiment about modernity–at least in the way they have appropriated it.

- REPLY TO LOUIS

RICHARD H. KINGAndy Seal’s complex and fascinating meditation on the problematic Parsons translation of “All that is solid melts into air” is a wonderful example of how close reading, with particular attention to tropes, can enrich our practice of intellectual history. (There should be a nod here to the importance of Hayden White’s lifelong effort to get us to read non-fiction texts in a sophisticated way.) Anyway, there is another influential misreading of another German text translated by Talcott Parsons that should also be mentioned. I refer to Parson’s translation of The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism where he renders Weber’s well-known “stahlhartes Gehäuse”as “iron cage.” In History and Theory, Vol. 40, No. 2 (May, 2001), 153-169, Peter Baehr has suggested that the translation should be something more like “shell as hard as steel”, a translation that has more frightening connotations than “iron cage.” In this article, Baehr also points out that the “iron cage” translation has its own power and has taken on a life of its own, a point Andy makes as well. Finally, I should add that in Chapter 13 (“Ideology and Terror”) of the 1958 edition of The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt refers several times to totalitarian terror as “an iron band”(“ein eisernes Band”) that compresses the diversity of human beings into one giant Human Being (“who makes out of many the One…”). See Origins, 2nd ed(1958), 466. Arendt did not share Karl Jasper’s near deification of Max Weber, but there is undoubtedly some anxiety of influence at work in Arendt’s formulation .

LOUISJust to note that “all that is solid” is not Parsons’ translation. It’s in the 1888 translation by Samuel Moore.

L.D. BURNETTAndy, I hate to be dim, but it can’t be helped. I have no German and no immediate prospects of acquiring it, and your many references to the German phrasing / wordplay of this passage might as well be written in Sanskrit for me. So I’m wondering if you could add (maybe in comments?) a three-fold reading aid: the whole passage whose meaning you’re discussing, the whole disputed translation of same, and then how you would translate this sentence or set of sentences.Thanks.

- REPLY TO L.D. BURNETT

ANDY SEALHi L.D.,

No problem! Well, to be honest, I don’t want to embarrass myself by trying to translate the whole paragraph, so I guess that’s a problem, but hopefully the German original and most common English translation side-by-side will help.Here is the whole paragraph in the German original:Die Bourgeoisie kann nicht existieren, ohne die Produktionsinstrumente, also die Produktionsverhältnisse, also sämtliche gesellschaftlichen Verhältnisse fortwährend zu revolutionieren. Unveränderte Beibehaltung der alten Produktionsweise war dagegen die erste Existenzbedingung aller früheren industriellen Klassen. Die fortwährende Umwälzung der Produktion, die ununterbrochene Erschütterung aller gesellschaftlichen Zustände, die ewige Unsicherheit und Bewegung zeichnet die Bourgeoisepoche vor allen anderen [11] aus. Alle festen eingerosteten Verhältnisse mit ihrem Gefolge von altehrwürdigen Vorstellungen und Anschauungen werden aufgelöst, alle neugebildeten veralten, ehe sie verknöchern können. Alles Ständische und Stehende verdampft, alles Heilige wird entweiht, und die Menschen sind endlich gezwungen, ihre Lebensstellung, ihre gegenseitigen Beziehungen mit nüchternen Augen anzusehen.And here is the most common English translation (by Samuel Moore, in 1888):The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionising the instruments of production, and thereby the relations of production, and with them the whole relations of society. Conservation of the old modes of production in unaltered form, was, on the contrary, the first condition of existence for all earlier industrial classes. Constant revolutionising of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.- REPLY TO ANDY SEAL

ANDY SEALAnd here are just the key clauses I’m focusing on:“Alles Ständische und Stehende verdampft, alles Heilige wird entweiht”

Moore, 1888: “All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned”

My stab: “Every [social] standing and all that is stationary evaporates, all that is holy is deconsecrated” - REPLY TO ANDY SEAL

L.D. BURNETTAndy, thank you so much!

- REPLY TO ANDY SEAL

- REPLY TO L.D. BURNETT

LILIAN CALLES BARGERI would like to add to this interesting discussion. The problem of translation is ubiquitous across scholarship. Example: The translation of de Beauvoir’s Le Deuxieme Sexe by H.M. Parshley is another example. The English translation of The Second Sex has been contested for decades producing realms of critique. This what de Beauvoir scholar Margaret Simon has to say about it:“Inadequate, inaccurate English translations of works by feminist scholars can slow the advancement of international research in women’s studies. We must begin to subject translations to the same critical attention we have focused on those sexist authoring and publishing practices that have defined women’s interests as tangential to scholarly research. Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, one of the most widely known, classic essays on women’s experience and a cornerstone of contemporary feminist theory, is available in only one English translation from the French. In that 1952 translation by a professor of zoology, Howard M. Parshley, over 10 per cent of the material in the original French edition has been deleted, including fully one-half of a chapter and the names of seventy-eight women in history. These unindicated deletions seriously undermine the integrity of Beauvoir’s analysis of such important topics as the American and European nineteenth-century suffrage movements, and the development of socialist feminism in France. Compounding the confusion created by the deletions, are mistranslations of key philosophical terms. The phrase, ‘for-itself’, for example, which identifies a distinctive concept from Sartrean existentialism, has been rendered into English as its technical opposite, ‘in-itself’. These mistranslations obscure the philosophical context of Beauvoir’s work and give the mistaken impression to the English reader that Beauvoir is a sloppy writer, and thinker. ” “The silencing of Simone de Beauvoir guess what’s missing from The Second Sex” in Womens Studies International Forum – WOMEN STUD INT FORUM. 6. 559-564.A new translation was offered in 2010 https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/2010/05/30/books/review/Gray-t.htmlAll to say that the weakening of language study and translation in graduate education does not serve intellectuals historians well. I feel hamstrung by lack of knowledge of German and minimal French. So, that means we have to be super diligent when working off translated works. However, since a bad translation to English can still have immense influence in its own right, does it matter? Is reception of the English version really all that matters in America not what was originally written in Europe?

- REPLY TO LILIAN CALLES BARGER

LILIAN CALLES BARGERExcuse the typos, I was in a rush. That’s reams.

- REPLY TO LILIAN CALLES BARGER

LOUISI’m surprised that there was only one English translation of The Second Sex up until 2010.The whole area of translation is dicey, I agree. Just one smallish example: a few months ago I stumbled upon the English translation of Élisabeth Roudinesco’s Freud: In His Time and Ours, orig. published in French in 2014 or thereabouts. Though I wasn’t reading the original, I can read French and I could tell that the translation in quite a few places was clunkily over-literal: phrases and sentences that would have sounded ok in French had been translated in such a way that they sounded awkward, verbose, and/or pretentious in English. Translators have a hard job and I don’t want to be too critical, but I was somewhat surprised that a major univ. press would issue what struck me as not a particularly good translation. (I only got through the first third or so of the book.)Of course if someone can’t read a particular work in the original, the best situation is to have many English translations to choose from and/or compare. I’m thinking of The Prince, of which there are many translations extant. That may be on the extreme end of the spectrum, but a fair number of classics prob. have been translated a number of times.

- REPLY TO LOUIS

LOUISObviously it”s not just Machiavelli who has lots of translators. A lot of writers in the (putative) canon do, from Plato and Aristotle onward. But the relative brevity of The Prince, coupled w its fame, may be one reason so many translations have been produced; it looks less daunting to a prospective translator than something longer. Just speculating…

- REPLY TO LOUIS

- REPLY TO LILIAN CALLES BARGER

Leave a comment