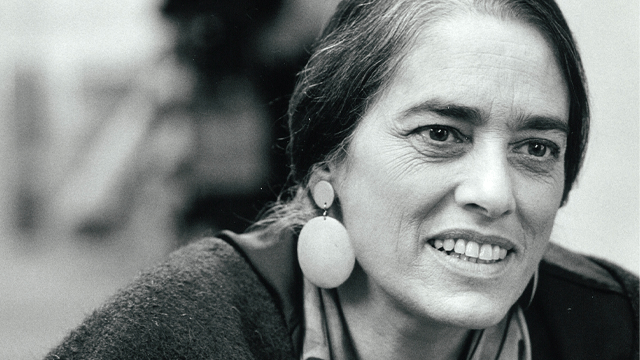

Evelyn Fox Keller, who passed away on 22 September 2023, was a leading figure in the field of Feminist Science Studies, a field that has gradually developed over the last three decades in India. Fox Keller visited the National Centre for Biological Sciences, Bengaluru, in 2004 on an invitation by biologist Obaid Siddiqi. Fox Keller gave lectures at select scientific institutions that were attended by many who are now leading figures in the field of feminist science studies in India. This memoir tribute, both personal and professional, highlights some of Fox Keller’s arguments on the need to reimagine the method of science and on the ethico-moral responsibility that must lie with the scientific establishment.

A Jungian Synchronicity

The digital immigrant that I am, Facebook is an important social space for me. As I readied my post to commemorate 100 years of Dev Anand on 26 September 26, I noticed that my friend and collaborator, Renny Thomas, had posted a link to a letter written by Obaid Siddiqi, the founder of the National Center for Biological Sciences (NCBS) in 2003 to Vijay Raghavan, who was the Director of NCBS at the time. The letter sought approval on a proposed visit of physicist–biologist-turned-historian-of-science and pioneer of Feminist Science Studies, Evelyn Fox Keller in 2004. The letter is presently stored in the NCBS Archives[1]. Siddiqi, in the letter, outlines the course EFK intended to teach at NCBS, including a lecture on Gender and Science.

On 21 September, I had begun to teach my course on “Modernity, Science and Gender: An Introduction to Feminist Science Studies” at the NCBS. When I saw Siddiqi’s letter on facebook, it almost seemed like a sign. Within minutes, it struck me that Renny’s post was a commemoration of EFK’s death, at the age of 87, on 22 September. She died a day after I started the course. I also discovered that EFK and I share a birthdate. In a rationalist paradigm of explanation, this set of events is an interesting coincidence, a matter of chance. In another paradigm, like the Jungian one, we are allowed to take cognitive and imaginative leaps. Carl Jung (1973), the analytical psychologist, introduced the concept of synchronicity to articulate the meaningful relationship we make between two things happening at the same time without a causal connection but with a subjective connectedness.

Either way, as I bid adieu to EFK, I recollect my connection with her. I write this article both as a personal tribute and as an account of some of her brilliant work.

***

I met EFK in 2004 at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR), Mumbai. As someone who had recently completed work on her PhD thesis in feminist science studies at the University of Mumbai, I found EFK’s visit and her talks of immense value. Given the fledgling nature of the field in India at that time, the visit was also important to the small number of academics and activists working in this area. By then, I had also been caught in the toxic polemics of the science wars through what is famously known as Sokal’s Hoax of the late 90s[2]. Alan Sokal had attacked social scientists and feminist critics of science accusing them of not being rigorous and of playing into right-wing politics. Soon the debate fell into pro- and anti-science positions. Sadly, the atmosphere to any form of science criticism, particularly feminist, became hostile and combative. Hence, my journey of working on developing a feminist framework to study scientific creativity, the role of intuition as an epistemic category, and the social making of the “genius” was a lonely one. Doing this doctoral work in an Indian state university on a modest fellowship from the University Grants’ Commission was a challenge. I remember giving lists of books to buy to friends going abroad. My fellowship money would all be spent in procuring books like Sandra Harding’s The Science Question in Feminism, Londa Schiebinger’s Nature’s Body, and Nancy Tuana’s edited volume called Feminism and Science. Each of these texts was pioneering in the field of feminist science studies and helped me a great deal to find arguments and frames for my work. But it was EFK’s Reflections on Gender and Science, which I found in the library of Vacha in Mumbai[3] that was the first text I fully imbibed. After that there was no looking back. I suspect the appeal of her writing lay in her layered, nuanced, and complex understanding of issues in feminism and science. The fact that she was a scientist herself, unlike some of the other scholars in the field, made it particularly special. Soon after, I found EFK and Helen Longino’s edited volume called Feminism and Science at the Centre for Education and Documentation[4] in Mumbai. I immediately photocopied and spiralbound these texts. They remain in that form in my personal library. I later figured that these texts were being read in the early 90s by a group of scholar activists in the Forum Against Oppression of Women, Mumbai (FOAW)[5]. One of them was Chayanika Shah, a queer feminist activist trained in physics. Chayanika Shah and I were to later collaborate on the first course in FSS at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai (Chadha and Shah 2015). While FAOW’s work was less known in academia, the work of Vandana Shiva, author of the bestselling book Staying Alive (Shiva 1988), was known both in academia and the larger public domain. There was little sense of a community among people working in feminist science and technology studies. Given this context, EFK’s visit in 2004 felt like a gift, a blessing to those of us looking into the question of gender and science. It is also clear that there was enough interest in her work among the scientific community. It was significant enough for her to be invited by Obaid Siddiqi. The story behind this invitation would be an interesting one to dig out to understand the history of institutional attempts to go beyond the silos. For this article, a personal tribute, I pick up on two sets of arguments from her work that made a big impact on me.

“Feeling for the Organism”: Fox Keller’s Classic

I remember listening to EFK with bated breath at the TIFR, which was both my home because I lived in the housing colony and my field because I had conducted research interviews with scientists at the institute. While I was fully aware of the intellectual merits of the paper she read out, I felt protective of her. I knew that in my “field-home,” typically dominated by highly privileged upper caste men, any critical gaze on science is generally met with denial, suspicion, dismissal, and judgement, especially if the gaze is a woman’s gaze. And yet, I would say, there are always some individuals who are driven by the curiosity to listen. From my experience of almost three decades in the field, I have learnt that we must bank upon this curiosity, with patience, as we traverse spaces across academic silos and disciplinary canons.

My recollections of EFK’s visit in 2004 are warm. I remember how she wore shades of soft green her trademark “bohemian” jewellery. I had seen pictures of her and had thought that hers, like Meryl Streep’s, is one of the most impressive faces I had ever seen. Clearly, I was in awe but that did not seem to touch her in any significant way. She knew how to make me feel equal. Considering she was almost my mother’s age, seeing her as the mother goddess of the field of feminist science studies came to me with surprising ease! EFK and I undertook a trip to Mumbai’s Chor Bazaar, looking at curios and antiques as we talked of the ethical questions behind Sokal’s Hoax and how it had shrunk the space of dialogue, something I still feel today. She had read my piece in Economic and Political Weekly. Our shared rage at being so badly misrepresented in the Sokal’s Hoax bridged many other gaps between us. As she picked up earrings for herself, we spoke of our reservations with some kind of post-modernist thought. Her emphasis on how language constructs knowledge leading to a “methodological relativism” was apparent. Her insistence on an “ontological realism” was equally persuasive. I must confess I see the value of this balance more clearly now than I did then. EFK heard me out on my academic loneliness, my work, and my difficulties. While we spoke of the need for us to collectivise as a global community of scholars, we recognised the politics of social location in academia. As much as we spoke of the need to be inclusive, we recognised the challenges of doing this on equal terms and in equal measures. Recounting her experiences of EFK’s visit to the Indian Institute of Science in Bangaluru, Asha Achuthan, now at the TISS, Mumbai, who was then a doctoral student at the Centre for Study of Culture and Society, Bengaluru, says “I remember hearing her somewhat hungrily… she was a bit of an idol… a mixed race group of students visiting IISc from Washington University had questions about white feminists taking space and speaking of vulnerable groups… I remember spending time with them, telling them what I thought Keller had done in and for the space of feminism and gender studies, and the need to acknowledge that.” Today, she says, as she discusses “the value of connecting the who that speaks with the what that is spoken, I salute Keller, for having bought ‘a feeling for the organism’ to me.” That the space of feminist science criticism was and is wholly dominated by the voices of white western women is a valid concern. But we need to recognise that this is not specific to feminist science studies. It is the generic truth of most intellectual pursuits in post-colonial societies and is being continuously corrected in some circles of academia. For instance, with the advent of an intersectional perspective, our pedagogic practices in FSS have seen a considerable change. In telling the story of gender discrimination in science, we recognise that it comes along with other axes of social discrimination, like race, caste, class, religion, sexuality, ableness compounding, and exacerbating the exclusionary culture of science. We use narrative experiences of Evelyn Fox Keller—the Jewish American white woman scientist, along with Evelyn Hammonds—the black woman mathematician, Ben Barres—the trans male mathematician, and Banu Subramaniam—the post-colonial woman scientist living in the west to bring forth an intersectional understanding of who gets to do science and who does not. We have also generated reflexive narratives of privilege in our own context. From women and gender non-conforming persons, these narratives provide insights into the gated culture of Indian science[6]. From my meeting with EFK in 2004 to today, I would say we have come a long way in addressing the question of women’s participation in science. We have rigorously begun to shift the spotlight on science, rather than on the generic “society,” to provide explanations and solutions on the problem of diversity in science.

EFK’s Feeling for the Organism: The Life and Work of Barbara McClintock (1983) is a classic text in feminist science studies. Written in 1984, it is probably regarded as the most authentic biographical account of the life of cytogeneticist Barbara McClintock. To my mind, it is a classic on the question of scientific method. It shows how the scientific method packs in tight codes of rationalism and tighter codes of gender. When I first found the book, my immediate impulse was to browse through the index to find the word “feminist” or “feminism”; there was not a single entry. Intrigued, I read the book and learnt how it is possible to do feminist work without naming it as that. While I have found great value in using the term in my own work, and in my own context, EFK’s book taught me to respect the oeuvre of not using the term “feminist” in every context. That aside, the book is a singularly insightful and sharp text. Apart from telling the story of Barbara McClintock in an authentic manner, thickly laden with McClintock’s own voice, the book has been, for many of us, a way to complicate several questions of knowledge production in science. First, EFK’s reading of McClintock begs the question: is there a feminist way/method of doing science? If yes, what is special about it, and is it accessible only to women? Since McClintock believed that science begins where gender drops, how do we as feminists read her work? EFK’s book does not offer simple answers, not to the feminist. In fact, the book marks a particular churning for feminists, especially for those who make a direct and simple equation between women and nature and argue for the consequent superiority of women in being able to understand nature holistically. The ability to be intimately connected to nature is largely attributed, in this discourse, to women’s biological role of birthing. EFK demonstrates, to the contrary, that McClintock had a “holistic,” non-reductionist, more connected approach to nature without undergoing any of the feminine or “womanly” biological processes of birthing or being involved in the social role of rearing children. McClintock actively inserted these things into her practice of the scientific method. EFK argues that McClintock’s ability to integrate her subjective “feeling for the organism,” to bring her intimate attentiveness to each and every plant in her field of study, to bring a language of care into her science, to almost being a mystic in her understanding of the oneness between the knower and the known- is not given only to women, per se. In arguing thus, EFK is suggesting that a non-reductionist way of looking at nature, even in science, is not exclusive to women and may be open to others if they wish and choose to do so. This is not to say that women are not better tuned into a more embodied understanding of nature due to their place in culture, which becomes a definite basis of feminist standpoint epistemology. To mistake this for an essential or innate ability is what she contests. EFK further argues that in the larger project of doing a non-reductionist science, McClintock’s practice might hold the key. It might help us gain a finer picture of the vital nature of an organism. This picture is best obtained, both McClintock and EFK would suggest, if we retain a “feeling” for things. I would say that this is an important tenet of feminist research methodology in the sciences, the principle of embodied reason, a reason that goes beyond the binary of the knower and the known.

Second, EFK’s book draws attention to another important aspect in the production of scientific knowledge: the mechanisms of how scientific knowledge gains validation and credibility in the scientific community. Is it only the “merit” of the argument that leads to the acceptance of new knowledge? Is it only the Popperian hypothetico-deductive method at work here? Or is Thomas Kuhn right in saying that it is social consensus among scientists that establishes the “truth” of a claim? EFK suggests that working on a problem that does not conform to the accepted practices of a discipline, as McClintock did, can often marginalise the scientist, whoever it may be, within the community. It takes time and persuasion. But she also confirms through her demonstration of McClintock’s career trajectory, including the very delayed Nobel prize McClintock was awarded, that scientific knowledge is established not only based on the Popperian model of the hypothetic deductive method but also on the emergence of social consensus within the scientific community as Kuhn suggested. And this process of consensus building, as Kuhnians know, is not a neutral one. It is here that social hierarchies are played out and cultural capital comes to play. One must necessarily be on the right side of the social hierarchy to obtain validation. EFK establishes that even though McClintock herself did not live in a gendered universe, she was discriminated against because she was a woman. EFK submits that McClintock’s struggles were exacerbated because she inhabited a female body, a fact that the scientific community found it hard to forget or did not choose to forget. McClintock was always perceived as a woman how much ever she would de-gender herself.

EFK’s layered arguments in her reading of McClintock’s life were stunning for me at the time and became pathbreaking for all of us in feminist science studies. They teach us that the “feeling for the organism” is an important epistemological principle that we have lost and need to restore in the practice of science and that this principle is not the exclusive prerogative of women as some feminists claim. Yet, women might be closer to it because of their socialisation and hence must be heard. They also teach us that woman, however much they attempt to erase their gender in their personal life and in their practice of science, it catches up because of the patriarchal culture of science. Our struggle, to have more women to do a “different” science, therefore, is more complex than it seems at first glance.

“Secrets of Life, Secrets of Death”: My Favourite Classic

The second set of arguments that I want to pick up from EFK’s rather vast work are those related to the ethico-moral aspects of science. In the 1st of July issue in 1946, the cover of TIME magazine represented the two faces of science: one, in its “pure” form—as knowledge for the sake of knowledge, innocent in intent and two—in its “applied” form, intended to be put to good use for human beings but also producing dangers and risks to humankind and the universe. TIME magazine juxtaposed these two aspects of science soon after the “Little Boy” and the “Fat Man,” the two atomic bombs that had been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki killing scores of innocent people. Modern societies, particularly of the global north, often put out these reminders of the Janus-like character of science. Albert Einstein’s face—recognised by many across the world as the quintessential maverick scientist, also well known for his pacifism—is placed along with the image of the mushroom cloud, recognised as the making of the atom bomb in Los Alamos, on the side. Einstein’s famous equation of relativity E = mc2 is placed on the cloud. In her analysis of this representation, EFK persuasively explores what she calls the “tragedy of science”: that at its purest, science can become most dangerous, that the dichotomy between the pure and applied is a surface level distinction. She further argues that while Einstein, as an individual scientist, cannot be held responsible for the creation of the atom bomb through his “notoriously abstract and obscure theory of relativity, the theory that was popularly said to be comprehensible to only twelve people in the world,” not all nuclear physicists involved in the production of the atomic bomb can be so absolved. She asks: can we hold the scientific establishment, science, and scientists accountable or not? In the Indian context, Ashish Nandy debunks the myth that the state alone is responsible for the misuse of science. He, like others in critical science technology studies, places the responsibility squarely on science. In the introduction to Science Hegemony and Violence: A Requiem for Modernity, he says “… the science establishment, on its own initiative, has taken advantage of the anxieties about national security and the developmental aspirations of a new nation to gain access to power and resources.”For analysts of the Manhattan Project, including J P S Uberoi, the Manhattan Project marks the end of a good, humane science committed to the idea of a better life and a better world. In his book, The European Modernity: Science, Truth and Method, Uberoi names the Manhattan Project as the final expression of a science gone rogue, a science based on Cartesian dualism, where mind and body, nature and culture, reason and emotion among many other things are separated, in a violent encounter with each other, as opposites, as binaries. Similarly, in feminist science studies, we arrive at a critical analysis of Cartesian dualism. In our own trajectory as a field that examines the gender binary to foreground women’s marginalised lives and knowledges in the making of science and the (un)making of other knowledge systems, we go back to the simultaneous formation of patriarchal gender ideologies and formation of modern western science. In outlining our “moral role” to offer alternatives from the margins, Uberoi seeks out the non-dualistic hermetic traditions of the west, and a Gandhian philosophy from India, as correctives to the principles and practices of western modern science. In a similar vein, Nandy’s volume has essays that draw alternatives from Vedic and upper caste approaches to nature. Sumi Krishna and I, in the essays in our volumes, attempt to draw upon women’s embodied imaginations and epistemes of nature, based upon their livelihoods and their lived experiences at various intersections of caste and class, to present alternatives to modern western science. We take the position in these essays that non-western or indigenous traditions of knowledge are neither free nor necessarily emancipatory. They are significant because they are living.

Waking “sleeping metaphors” was an important aspect of Fox Keller’s work. As Prajval Shastri, the astrophysicist remembers, “…She opened my eyes to how metaphors influenced our praxis, which indeed was another pathway to systemic patriarchy that weakens our scientific outcome! I was utterly disbelieving at first, because, for me, mathematics was the language of physics where metaphors had no place and physics was neutral to the quality of the spoken or written word. But then her compelling example of research on the development of zygote really demolished that for me like a thunder…”

EFK, in her lesser-known classic, Secrets of Life, Secrets of Death: Essays on Science and Culture (1992) analyses the history of molecular biology and modern physics. In this book, she engages with the metaphor of “secret” in the discourse in and around science. In her exposition, she shows how modern western science sees the “secret of nature” as a threat, attempting to violently break it open. Feminist scholars like EFK who deploy the psychoanalytic perspective show how this perception of nature extends to women. Women, they argue, are seen as mysterious, possessing the secret of life. They hold the “power” of birthing and inspire, like nature does, fear in men. While this kind of analysis runs the risk of essentialising gender, and one must contest that the description it offers is significant. Deploying the psychoanalytic perspective, EFK shows how the discovery of DNA removes all sense of life around the molecule to get down to the elemental structures. Much like what physics did with the atom—though the cutting off life from the process is much more dynamic in biological research than in physics—both were, she says, determined to crack open the secrets of life, and of nature, to “improve” the human condition. Both, she says, have a tactile gendered character to them. These histories feminise nature and women; stripping them off agency and controlling them in violent ways. She establishes that these attempts to unlock the secrets of life, and nature, have led to the unlocking of secrets of death.

As I bid adieu to Evelyn Fox Keller with gratitude in my heart, I recognise that there will never be simple solutions in the dark times ahead and the light of reason must prevail. But the idea of reason itself needs to be reimagined. EFK’s scholarship in this direction is vast and rigorous, her vision sharp. If there is genius in attribute, it is here.

Leave a comment