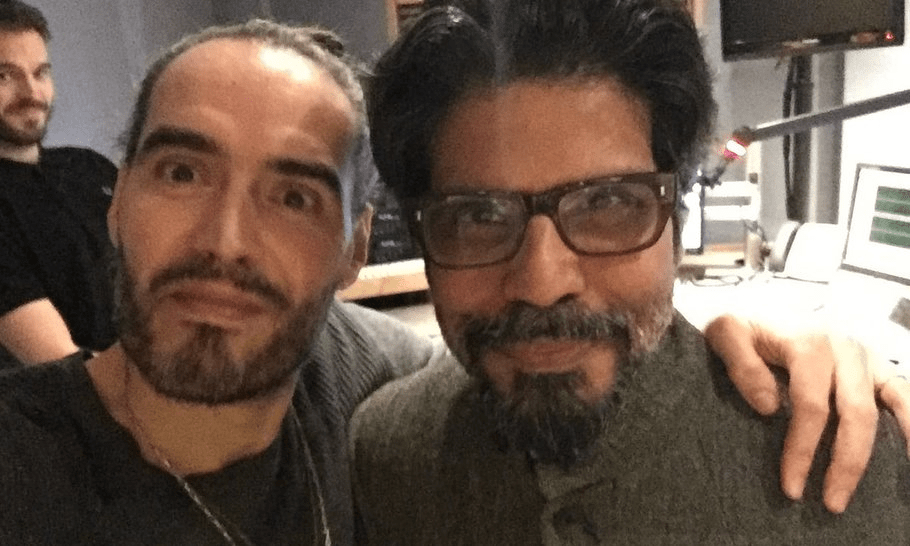

Russel Brand & Pankaj Mishra (as posted on Twitter (now X) on Dec 2, 2017)

Many years ago, I stopped buying The London Review of Books because under Mary-Kay Wilmers it consistently published articles which criticised Israel and didn’t attempt to balance these with articles supporting Israel. So, I wasn’t surprised to see that the LRB has just published a 7498-word article by Pankaj Mishra attacking Israel, “The Shoah after Gaza.” Nor was I surprised that the article was full of omissions, bias and hostility towards Israel. As the scorpion says to the frog, “It’s in my character.”

But I was surprised that Selwyn College, Cambridge, having invited Mishra to give the 2024 VS Naipaul Lecture on 12 March, just a few days after the publication of his article attacking Israel, did not choose to reconsider its invitation. Of course, they have a legal right to invite any speaker they choose and he has the right to give the lecture. The issue is not about legality. It is about decency and respect for minorities. Had Mishra written in this way about any other ethnic minority in Britain I don’t think the LRB would have published it and Selwyn might have thought twice about inviting him. But as David Baddiel (a man of the Left) has written, “Jews Don’t Count” — at least, not in the same way as other minorities.

Why would a Cambridge college wish to invite the author of such an article to speak at a time when Jews are facing growing hostility in many of our universities and cities? They have a legal right to add to the toxic atmosphere facing many Jews in Britain today, by inviting someone who has written such a vile article attacking Israel, but why exercise that right? Why not think that now might not be the best time to offend British Jews, when so many of us feel afraid and isolated?

What is it about Mishra’s article that is so unpleasant? It is not that it is an all-out attack on Israel or that it accuses Israel of exploiting the memory of the Holocaust in the most disturbing ways. There is no shortage of criticisms of Israel or arguments that Israel exploits the memory of the Holocaust. Mishra begins by quoting well-known Holocaust survivors, like Jean Améry and Primo Levi, who criticised Israel. Améry, he writes, once said that Prime Minister Begin, “with the Torah under his arm and taking recourse to biblical promises”, speaking openly of stealing Palestinian land, “alone would be reason enough for the Jews in the diaspora to review their relationship to Israel”. He pleaded, writes Mishra, with Israel’s leaders to “acknowledge that your freedom can be achieved only with your Palestinian cousin [sic], not against him.”

Primo Levi, he writes, said that “Israel is rapidly falling into total isolation … We must choke off the impulses towards emotional solidarity with Israel to reason coldly on the mistakes of Israel’s current ruling class. Get rid of that ruling class.” Many people, Jews and non-Jews alike, might feel the same way about Netanyahu and his government today.

Mishra then quotes Yeshayahu Leibowitz, a theologian, who warned in 1959 against what he called the “Nazification” of Israel. He also cites the Israeli columnist Boaz Evron who, he says, criticised the tendency to conflate Palestinians with Nazis and shouting that another Shoah is imminent which, he feared, was liberating Israelis from “any moral restrictions, since one who is in danger of annihilation sees himself exempted from any moral considerations which might restrict his efforts to save himself.” Jews, Evron wrote, could end up treating “non-Jews as subhuman” and replicating “racist Nazi attitudes”.

There is much more he could have quoted from these and other Israeli authors. The problem is not that he quotes them, but that he doesn’t put these quotes in any kind of context by acknowledging that they were not representative of Israeli intellectuals. They were both longtime critics of the state of Israel and well known for their outspoken views. Mishra continues in the same vein, seeking out other provocative critics of Israel, whether other Israelis or foreigners, like Zygmunt Bauman and George Steiner, and making no attempt at all to balance these with any supporters of Israel. Another editor would have asked for some kind of balance in his piece and some attempt to provide background information about the people he’s quoting.

You may think this is just sloppy by Mishra. Where’s the offence? One of the striking features of the debate since 7 October has been that critics of Israel have routinely accused Israel of “genocide” and have often compared the deaths of Palestinian civilians with the Holocaust.

This is not a coincidence. They want to show that the relationship between Israel and the Holocaust is exaggerated and that Israel is more like Nazi Germany. The real victims, they say, are not Israelis but the Palestinians. Of course, this is said to deliberately offend Jews, by taking our most painful memories of loss, and saying: you’re not the real victims. Look how you exploit your history by becoming the new Nazis.

The timing is significant. They make this argument when there are still survivors of the Holocaust living in Israel, to trash their memories. And how better than by quoting Holocaust survivors like Levi and Améry, who criticised Israel?

That’s why it is no coincidence that in almost 8,000 words Mishra doesn’t mention October 7 or the hostages, doesn’t mention Iran at all, and mentions Hamas only twice. Of course, Israel can seem like the perpetrator, if you never mention those who want to slaughter its people. Israel is not perpetrating genocide. Given the chance, Hamas and Iran certainly would.

Similarly, Mishra makes no reference to any of the pogroms before 1948, any of the invasions of Israel in 1948 and since, or the expulsions of Jews from every single Muslim country in North Africa and the Middle East. All of this is airbrushed from history. For Mishra it simply never happened. None of it.

Instead, he writes about “the targeted killings of Palestinians, checkpoints, home demolitions, land thefts, arbitrary and indefinite detentions, and widespread torture in prisons seemed to proclaim a pitiless national ethos: that humankind is divided into those who are strong and those who are weak, and so those who have been or expect to be victims should pre-emptively crush their perceived enemies.”

And then, of course, we come to Gaza and “the victims of Israeli barbarity [sic] in Gaza today”. Mishra goes on to distort the history of the current conflict with Hamas (who are virtually invisible in his account). “Worse,” he writes, “the liquidation of Gaza” [sic] “is daily obfuscated, if not denied, by the instruments of the West’s military and cultural hegemony: from the US President claiming that Palestinians are liars and European politicians intoning that Israel has a right to defend itself, to the prestigious news outlets deploying the passive voice while relating the massacres carried out in Gaza.”

There is not a single reference to the support of the UN, UNWRA and a number of NGOs for Palestinians and their constant use of data taken from the Palestinian Health Ministry (better known as Hamas), the worldwide support for Palestinians in Gaza and the biased pro-Palestinian coverage on the major British and American news networks. All of this is simply ignored.

Then we come to the familiar rhetoric of post-colonial self-pity, or what he calls “a long-simmering racial bitterness”. “In 2024,” he writes, “many more people can see that, when compared with the Jewish victims of Nazism, the countless millions consumed by slavery, the numerous late Victorian holocausts in Asia and Africa, and the nuclear assaults on Hiroshima and Nagasaki are barely remembered.”

Really? Have we really all forgotten about Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or about slavery? It’s more likely that some of us have forgotten or never knew about the terrible crimes committed by non-whites: the rape of Nanking, the millions of victims of Indian Partition, the slaughter of countless Muslims by tyrants like Assad and Saddam Hussein, the role in slavery of Africans and Arabs, the homophobia and misogyny of countless Muslim regimes, the ongoing persecution of Christians in many parts of Africa and the Middle East and the desperate plight of girls and women in Iran and Afghanistan. Again, no reference to any of this history, past or present.

Mishra’s essay is also full of omissions and distortions. He writes, “When I look at my own writings about the anti-Muslim admirers of Hitler and their malign influence over India today, I am struck by how often I have cited the Jewish experience of prejudice to warn against the barbarism that becomes possible when certain taboos are broken.” Curiously, he forgets to mention the Muslim admirers of Hitler — in particular, the Palestinian admirers of Hitler such the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin Al-Husseini.

Then we come, inevitably, to the unique perfidy of Israel. “Israel today,” he writes, “is dynamiting the edifice of global norms built after 1945, which has been tottering since the catastrophic and still unpunished war on terror and Vladimir Putin’s revanchist war in Ukraine. The profound rupture we feel today between the past and the present is a rupture in the moral history of the world since the ground zero of 1945.”

This isn’t just hyperbole. It is bad history. Where were these “global norms built after 1945” when there was genocide in Bosnia and Rwanda, the terrible wars between Iran and Iraq, the mass slaughter in Cambodia, civil wars in Nigeria and Syria, all with fatalities which dwarf what has happened so far in Gaza?

On every page, there are errors, omissions, distortions and hyperbole. Of course, because this presumably fits the world view of the editors and many of the readers of the LRB. This hatred of Israel, the anti-colonialist rants and the silences about Hamas, Muslim support for the Nazis, and Muslim antisemitism in Africa and the Middle East, are all part of the new progressivist ideology in our universities, our mainstream TV news networks and newspapers like The Guardian. He is preaching to the converted. It is the orthodoxy of our age.

That’s why it’s important to condemn Mishra’s polemic in some detail and to ask why the authorities at a Cambridge college think he is an appropriate person to give a lecture in memory of VS Naipaul, of all people, who was one of the great truth-tellers about the tyrants and slaughterhouses of the post-colonial world. Naipaul would have relished the irony, but he would also have condemned Selwyn College for betraying his memory.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.

Pankaj Mishra

India and Israel: An Ideological Convergence

Written for This Is Not a Border: Reportage and Reflection from the Palestine Festival of Literature (2017)

Literary festivals, for most writers, are a release from prolonged and solitary labour. The few obligations of authors – solo talks or panel discussions – are lightened by the thrill of being recognised, even lauded; and any enforced sociability with prickly compatriots is sweetened by free alcohol and adoring groupies. PalFest, which I accompanied in its very first incarnation, may be the world’s only literary festival that broadens the mind and deepens the heart.

I certainly cannot overestimate its revelatory quality. I grew up among fervent Zionists, who were either ignorant or disdainful of Palestinians. One of the first books that I read in English was Ninety Minutes at Entebbe, the account of a daring Israeli raid in Uganda to free hostages captured by Palestinian militants; and one of my earliest heroes was the Israeli general Moshe Dayan. I was introduced to both in the 1970s by my grandfather, an upper-caste Hindu nationalist. He recounted keenly how Dayan had outmanoeuvred numerically superior Arab armies in 1967; how he had snatched the Golan Heights from Syria at the last minute.

India did not have diplomatic relations with Israel until the 1990s. My grandfather was among many high-caste Hindus who idolised Israel because it possessed, like European nations, a proud and clear self-image; it had an ideology, Zionism, that inculcated love of the nation in each of its citizens. Most importantly, Israel was a superb example of how to deal with Muslims in the only language they understood: that of force and more force. India, in comparison, was a pitiably incoherent and timid nation-state; its leaders, such as Gandhi, had chosen to appease a traitorous Muslim population.

This is what I also believed as a curious child. I remember that when news of Dayan’s secret visit to India in 1978 as Israel’s foreign minister leaked, and pictures of him appeared in the Indian newspapers, I was transfixed by his black eyepatch and mischievous grin.

As I grew older, I became aware of the plight of Israel’s victims. There were Palestinians in small Indian cities, mostly students at engineering and medical colleges, and their dispossession was often discussed in the left-wing circles I fell into at university. But even then Palestine signified to me a tragically unresolved dispute, in the same way that Kashmir did, between parties that had somehow failed to see reason.

In 2000 I went on a reporting trip to Kashmir, where tens of thousands of people had died in an anti-Indian insurgency and counter-insurgency raging since 1989. Hindu nationalists have long vended an image of Indian Muslims as fifth columnists breeding demographic and other vast anti-national conspiracies in their urban ghettos. In fact, Muslims are the most depressed and vulnerable community in India, worse off than even low-caste Hindus in the realms of education, health and employment, frequently exposed to bigoted and trigger- happy policemen. Their condition has deteriorated in recent decades. After dying disproportionately in many Hindu– Muslim riots, more than 2,000 Muslims were killed and many more displaced in a pogrom in 2002 in the western Indian state of Gujarat, then ruled by a hard-line Hindu nationalist called Narendra Modi. But, as I discovered in 2000, India, in the eyes of Kashmiri Muslims, had never been less than a Hindu majoritarian state despite its claims to secularism and democracy.

Seven years later, the trip to the West Bank with PalFest brought me face to face with the brutality, squalor and absurdity of the occupation. Far from being embroiled in a mere ‘dispute’ with its neighbours, Israel, it became clear, is the world’s last active colonialist project of European origin, sustained by high-tech armoury and the fervour and guilt of many powerful white people in the West. I also realised, like many visitors to the region, how much Israel’s claim to represent the victims of the Holocaust serves to hide the cruelties it inflicted on its captives in the West Bank and Gaza. For me, however, PalFest also unveiled another way of looking at India: together with Israel, another ‘secular’ and ‘democratic’ country.

It has made it easier for me to understand the extraordinary ideological convergence, so much hoped for by my grandfather and others and now accomplished, between countries that had started out as formally democratic and economically left wing. Their cosmopolitan founding fathers – Nehru, Gandhi, Ben-Gurion, Weizmann – and egalitarian ideals helped give the new nation-states, both created within months of each other, their glow of heroic virtue. It mattered little during their early years that both countries were born of imperialist skulduggery and nationalist opportunism, of clumsy partition, war and frenzied ethnic cleansing, or that, in the case of Israel, the inferior status of Arabs was formalised in citizenship rules.

As it happened, a mere decade – between 1977 and 1989 – separated their political transformations, when hard-line right-wing groups long deemed marginal – Likud, the BJP – began to change the political culture of the two countries. Unrest in occupied territories (the Intifadas of 1987 and 2000, and Pakistan-aided insurgency in Kashmir from 1989) helped give the post-colonial nationalisms of India and Israel a hard millenarian edge. In the 1990s both countries embarked on a deeper economic and ideological makeover, rejecting ideals of inclusive growth and egalitarianism in favour of neo-liberal notions about private wealth creation.

That process is now complete. Narendra Modi is now India’s most powerful prime minister in decades while tens of thou-sands of his Muslim victims in Gujarat still languish in refugee camps, too afraid to return to their homes. A portrait of the Hindu nationalist icon V.D. Savarkar, one of the conspirators in Gandhi’s assassination in 1948, now hangs in the Indian parliament. When Netanyahu won re-election in 2015, Modi tweeted his congratulations to his ‘friend’ in Hebrew (Israel is now one of India’s biggest arms suppliers). The two prime ministers, both lovers of free markets, flourish in the ideological and emotional climate of globalisation, in which, backed by popular consent, violence and cruelty enjoy a new legitimacy.

Kashmir has for years been subject to a draconian Armed Forces Special Powers Act, which grants security forces broad-ranging powers to arrest, shoot to kill, and occupy or destroy property. The summer of 2016 witnessed, in addition to the routine killing of scores of protestors, a sinister escalation: mass blindings, including of children, by pellet cartridges that explode to scatter hundreds of metal pieces across a wide area. Right-wing demagogues in both India and Israel seek to forge a new national identity – a new people, no less – by stigmatising particular religious and secular groups. And, as though emboldened by them, security forces in Kashmir this summer attacked hospitals and doctors in a display of impunity that was worthy of the Israel Defence Force.

Indeed, fanatical Hindu organisations that assault Muslim males marrying Hindu women seem to mimic Lehava (Flame), an association of religious extremists in Israel which tries to break up weddings between Muslims and Jews. A lynch-mob hysteria in significant parts of the public sphere – traditional as well as social media – fully backs the atrocities of security forces in Kashmir and Palestine. More importantly, bigotry is now amplified in both countries from people placed on the commanding heights of government.

A senior minister in Narendra Modi’s cabinet last year described Indian Muslims and Christians in India as ‘bastards’. Staffing educational and cultural institutions with zealots, both governments seem obsessed with moral and patriotic indoctrination, reverence for national symbols and icons (mostly far right), and the uniqueness of (a largely invented) national history. The supremacism of these ethnonationalists goes with a loathing of dissenters who seem to be undermining collective unity and purpose. Indeed, the most striking aspect of the upsurge of fanaticism in India and Israel is mob fury, sanctioned by their ruling classes and stoked by the media, against anyone who expresses the slightest sympathy with the plight of their victims.

Lost in a moral wilderness, India and Israel make one ponder, even more than the unviable and fragmenting states of the Middle East, the paths not taken, the missed turning points, in the history of the post-colonial world. But it is hard not to suspect that figures like Modi or Avigdor Lieberman are the clearest consummation of the European-style nationalism that my grandfather so admired. Murdered by a Hindu fanatic who accused him of being soft on Muslims, Gandhi was an early victim to its deadly logic. It is now manifest in the brutal occupations of both India and Israel – nation-states that are, as PalFest first revealed to me, committed to not resolving their foundational disputes.

Leave a comment