What the Mahagathbandhan leaders can learn from Ram Manohar Lohia

01 January, 2019

{ONE}

ON THE EVENING OF 10 DECEMBER 2018, a day before the results of assembly elections in five states were announced, India’s biggest opposition leaders began trickling into the Parliament House Annexe in Delhi. The politicians in attendance included Sonia and Rahul Gandhi of the Congress, Chandrababu Naidu of the Telugu Desam Party, Sitaram Yechury of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), Mamata Banerjee of the Trinamool Congress, Tejashwi Yadav of the Rashtriya Janata Dal and Arvind Kejriwal of the Aam Aadmi Party, among others. While some of these leaders are sworn political adversaries, they had been brought together for a common cause—dethroning the Bharatiya Janata Party in the 2019 Lok Sabha election.

The tension in the room was palpable. The organisers—the meeting was coordinated by Naidu—had not realised that Yechury and Banerjee could not be seen sitting next to each other, given the bitter rivalry between their parties in West Bengal. The arrangement was quietly changed and the Nationalist Congress Party’s Sharad Pawar was placed between them. However, the two multilingual rivals did exchange icy greetings in Bangla. “Kamon achhen”—how are you, Mamata asked; “Bhalo achhi”—I am fine, Yechury replied.

Representatives from the Samajwadi Party and the Bahujan Samaj Party were notably absent from the meeting. According to a senior communist leader who did not want to be named, the two Uttar Pradesh parties do not want to be seen working under Congress leadership. After the election results the next day, however, the SP’s Akhilesh Yadav tweeted in support of the coalition.

“Our purpose and goal is clear at the moment,” Akhilesh told me in an email interview on 20 December, “that we fight for the future of the country. Egos, personal ambition and short-term political benefits will all have to be weighed against what is in the national interest.”

While Akhilesh told me that seat-sharing details have been fixed, they have not been made public yet. A senior SP leader told me that both parties feel they would not be willing to spare more than five of the state’s 80 Lok Sabha seats for the Congress. Presumably, these numbers will be key in deciding if the three fight the election together in Uttar Pradesh. In a blow to the alliance efforts, the BSP announced on 24 December that it would be contesting all the Lok Sabha seats in Madhya Pradesh on its own.

In other states as well, the contours of the eventual coalition are still blurry. Thus, when the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam leader MK Stalin suggested the creation of a “national front,” the response was muted. Even the idea of a joint statement was found unpalatable—for Kejriwal and Yechury, it would mean being signatories alongside their respective rivals, the Congress and the Trinamool Congress. Most of the meeting was spent discussing the present government’s excesses, and its growing control over democratic institutions. Despite their differences, the parties seemed to agree that they needed to do their bit in dislodging the BJP. Eventually, the leaders decided to address a joint press conference after the meeting.

Even as a large anti-BJP coalition is beginning to take shape, it seems clear that this might not be a nationwide alliance. With the Congress tying up with as many regional parties as possible, there will be states where there will be no alliance, Yechury told me a few days before the meeting. “I call them question-mark states,” he said. “For instance, there will be no alliance in West Bengal, Kerala and Tripura.” He mentioned Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Maharashtra, Telangana, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh as states where pre-poll alliances were possible. The parties in the anti-BJP camp that might not enter pre-poll alliances may extend support to a coalition government after the elections.

Still, there are several roadblocks to putting together a coalition that could effect a regime change. After its success in the recent assembly elections, the Congress risks getting overconfident—it may demand a higher number of seats from regional players, or may reject alliances if not alotted the number of seats it wants. Seat-sharing deals would require an appetite for sacrifice and compromise, from both the Congress and the other players. Regional squabbles in states such as Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Bihar and Delhi could threaten the partnerships.

Even with an alliance that looks strong in numbers, the biggest challenge would be putting together a larger ideological programme. If the intent to dethrone the BJP remains the only raison d’être of the coalition, there would be nothing stopping it from falling apart right after the election. The most difficult task ahead, then, is not of figuring out who would contest from which seat, but the intellectually demanding one of developing a vision that all allies can get behind.

When I asked the politician and commentator Yogendra Yadav whether the opposition had anyone capable of accomplishing this, he told me, “The entire anti-Modi camp is devoid of intellectual resources.”

IN 2014, the BJP became the first party in 30 years to win a majority in the Lok Sabha on its own. Since then, the party has accumulated strength beyond its numbers. What seems unprecedented is the amount of control it exerts over nearly every key institution in the country. The government’s influence and interference have been noted just about everywhere—from the media, judiciary and investigative agencies to bodies such as the Election Commission, the Central Vigilance Commission and the Reserve Bank of India. It has gone about changing curricula and content in schools and colleges to realign the country’s education system to its Hindutva ideology. The space for dissent, or even disagreement, has been shrinking.

In this context, the parties in the opposition may be right to see the 2019 battle as a fight for not only their own survival, but to save Indian democracy.

In the 1960s, Indian democracy seemed to be in similar danger, when the dominance of the Congress had seemingly reduced the country to single-party rule. The party had won elections in 1952, 1957 and 1962 with brute majorities, and seemed to be heading in the same direction in 1967. That year, the British columnist Neville Maxwell wrote that India was no longer a democracy. “The great experiment of developing India within a democratic framework has failed,” he wrote. “In such circumstances, something will have to give in and it seems that the system will go fast.”

When I asked the politician and commentator Yogendra Yadav whether the opposition had anyone capable of accomplishing this, he told me, “The entire anti-Modi camp is devoid of intellectual resources.”

The 1967 elections went much differently than many had anticipated. At the time, the national and state elections were conducted simultaneously. Though the Congress still managed to win a majority in Lok Sabha, it won its lowest tally since Independence. The blow was strongest in the assembly elections, where the Congress lost power in eight states. Writing in The Statesman, the journalist Eric da Costa described the elections as the “1967 Revolution.”

“The centre holds firm but it’s an island,” da Costa wrote, referring to Delhi. The capital was “the only Congress-administered area in the long journey from Amritsar to Howrah.”

It was a watershed moment in Indian political history—the Congress’s monopoly over the country had come to an end. Finally, non-Congress parties had room to grow.

The man who brought down the Congress monolith was one of the most important figures in contemporary Indian history—Ram Manohar Lohia. “Lohia was so disgusted with the Congress raj and the incompetence and subservience of the Opposition that he had dedicated himself, with an amazing singleness of purpose, to the task of destroying Congress rule,” Madhu Limaye, a socialist leader who was a close aide of Lohia, wrote in his book The Birth of Non-Congressism. “He could not imagine that anything could be worse than the Congress as it had evolved by 1967. He thought that without the work of destruction, no work of construction could ever begin.”

In the 1960s, Lohia developed a strategy of “non-Congressism”—uniting the opposition against the Congress. His alliances were not built overnight. Lohia had begun putting them together right after the 1962 election. He had a deep understanding of Indian culture and society, which he combined with what he called “principled politics.” He provided a vision that a wide spectrum of leaders could get behind. Though the 1967 elections initially seemed a success for Lohia, his initiative would ultimately end in tragedy. It would take ten years after his death for the Congress to be dislodged at the centre.

The importance of Lohia to this moment has been acknowledged not only by several leaders of the mahagathbandhan, or a grand coalition, but also by the prime minister Narendra Modi himself. While today’s mahagathbandhan might not have a Lohia who can carry everyone together, there are several lessons its leaders can draw from his trials and triumphs.

{TWO}

RAM MANOHAR LOHIA WAS BORN ON 23 MARCH 1910 to a wealthy Baniya family in the city of Akbarpur, in what is today Uttar Pradesh. He moved to Bombay at an early age with his father, who was a member of the Congress and a supporter of the struggle against British rule. Lohia became politicised at a young age. He is believed to have organised a hartal in his school in Bombay as a ten-year-old so that students could go and pay their respects to the freedom fighter Bal Gangadhar Tilak, after his death in August 1920.

Soon after Lohia entered Calcutta’s Vidyasagar College for his bachelors degree, he got involved in student politics. He was introduced to Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhash Chandra Bose. According to Indumati Kelkar’s biography, Dr Ram Manohar Lohia, his Life and Philosophy, Lohia and Nehru immediately hit it off.

For his postgraduate studies, Lohia went to Germany’s Humboldt University, where he became a student of the leading economist Werner Sombart. Lohia’s time under Sombart had a tremendous influence on his worldview. Not only did Sombart introduce him to socialist economics, his varied career as a social activist, sociologist and economist provided Lohia a model to emulate. He observed the workings of German political parties closely, and attended several parties’ meetings, including four addressed by Adolf Hitler.

“Realising that he could not control Lohia,” Limaye writes, “Nehru became increasingly exasperated with him and his resentment showed.”

In 1930, on learning the news of a brutal lathi charge on satyagrahis in Dharasana, Lohia went to Geneva, where the League of Nations was in session. As the maharaja of Bikaner was praising the British government, Lohia whistled from the visitors’ gallery to heckle him before being taken away. He wrote to the editor of Humanité, a Geneva daily, highlighting the Dharasana incident—in which many satyagrahis, including his father, were injured—and questioning the decision to send a British lackey such as the maharaja to be India’s representative to the League. When the following day, the paper published his letter, Lohia distributed it to the delegates attending the session.

After finishing his doctoral thesis, on the salt tax and Mohandas Gandhi’s satyagraha against it, in 1933, Lohia returned to India and joined the Congress. He was one of the founders of the Congress Socialist Party—a caucus within the Congress—and the editor of its mouthpiece, the Congress Socialist. In 1936, Nehru appointed him the party’s foreign secretary.

Madhu Limaye, in The Birth of Non-Congressism, gave a comprehensive account of Lohia’s time in politics. In the early years, Lohia was enthralled by Nehru’s personality and saw him as his leader. But, in the early 1940s, Lohia began to diverge from Nehru on crucial topics such as socialism, imperialism and economics. “Realising that he could not control Lohia,” Limaye wrote, “Nehru became increasingly exasperated with him and his resentment showed.”

Soon after Independence, Lohia—along with other prominent members of the Congress Socialist Party such as Jayaprakash Narayan, famously known as JP, as well as Basawon Singh and Narayan Dev—left the Congress to form the Socialist Party.

Lohia became a relentless critic of Nehru. He had been against Partition, which he blamed on Nehru and Vallabhbhai Patel. In his book, Guilty Men of India’s Partition, Lohia gave an account of a crucial meeting of the Congress Working Committee in which Partition was discussed with Gandhi. Lohia and JP were present at the meeting. Lohia claimed that Nehru was economical with the truth while discussing Partition with Gandhi. He wrote,

I should like especially to bring out two points that Gandhiji made at this meeting. He turned to Mr Nehru and Sardar Patel in mild complaint that they had not informed him of the scheme of Partition before committing themselves to it. Before Gandhiji could make his point fully, Mr Nehru intervened with some passion to say that he had kept him fully informed. On Mahatma Gandhi’s repeating that he did not know of the scheme of Partition, Mr Nehru slightly altered his earlier observation. He said … that, while he may not have described the details of the scheme, he had broadly written of Partition to Gandhiji.

Lohia remembered Nehru and Patel being “offensively aggressive” to Gandhi. “What appeared to be astonishing then, as now, though I can today understand it somewhat better, was the exceedingly rough behaviour of these two chosen disciples towards their master,” he wrote. “There was something psychopathic about it. They seemed to have set their heart on something and, whenever they scented that Gandhiji was prepared to obstruct them, they barked violently.”

Lohia was careful to make a distinction between his anti-Partition view and the demand of the Jan Sangh, the BJP’s predecessor, for an “undivided India.” He castigated the Jan Sangh and its associates for having helped Britain and the Muslim League in the conception and execution of Partition. “They did almost everything to estrange them”—Hindus and Muslims—“from each other,” Lohia wrote. “Such estrangement is the root cause of Partition. To espouse the philosophy of estrangement and, at the same time, the concept of undivided India is an act of grievous self-deception, only if we assume that those who do so are honest men.”

The socialism of the Congress and Nehru, he felt, was merely lip service. Lohia saw the Congress as a right-wing party in disguise. He argued that Congress rule was by and for the wealthy, dominant-caste and English-speaking elite. (He began advocating the use of Hindi over English.) Lohia chided the party for being funded by the rich, even as it garnered votes from the poor.

Lohia rejected the communists too, arguing that they ignored caste. The political scientist Rajaram Tolpadi has written that Lohia was trying to create an indigenous model of socialism, indepedent of Western interpretation. Lohia argued that Marx’s theory of society was anchored in the history of the West, divorced from the reality of the colonised world of Asia, Africa and Latin America. He adopted a policy of equidistance from capitalism and communism.

With time, caste became more and more integral to Lohia’s socialism. The political scientist DL Sheth, an honorary senior fellow at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, recalled hearing Lohia in Baroda during the 1950s. “Lohia’s main message was jaati-todo”—break caste barriers—“which included not wearing the sacred thread and dropping caste names,” Sheth told me. “He carried out a strong anti-caste movement.”

Lohia saw the Congress as a right-wing party in disguise. He argued that Congress rule was by and for the rich, dominant-caste and English-speaking elite. He chided the party for being funded by the rich, while garnering votes from the poor.

The Socialist Party’s idealism, however, did not translate into electoral success. The 1952 general election came as a rude shock to the socialists, many of whom had thought that JP’s personal popularity could compete with that of Nehru. The Congress swept the polls, winning almost three-fourths of the seats in the Lok Sabha. The election results caused a fissure in the socialist movement regarding the party’s future course—while some, such as JP, wanted to cooperate and work closely with the Congress, Lohia’s camp was dead against it and wanted to play the role of a militant opposition. In 1955, Lohia broke from what was now known as the Praja Socialist Party to create a new outfit, again called the Socialist Party. One wonders how different India’s political history would have been had JP and Lohia found a way to work together.

Lohia was desperate to induct the Dalit leader BR Ambedkar into his new party. In a 2018 article for The Print, Anurag Bhaskar, a law student, detailed Lohia’s attempts to get Ambedkar on board. On 10 December 1955, Lohia wrote Ambedkar a letter. He invited him to write an article for his new journal Mankind, in which he wanted Ambedkar to “reveal the caste problem in its entirety.” Lohia mentioned the speeches he had made about Ambedkar in a parliamentary campaign in Madhya Pradesh. He went on to say that he wanted Ambedkar to become “a leader not alone of the scheduled castes, but also of the Indian people.”

Some of Lohia’s colleagues met Ambedkar in September 1956 to discuss a possible alliance between the Socialist Party and Ambedkar’s All India Scheduled Castes Federation. Ambedkar wrote back to Lohia on 24 September 1956, saying that he intended to meet him during his next visit to Delhi. In the letter, Ambedkar stressed the need for a strong opposition in a democracy, and was in “favour of a new political party with strong roots.”

On 1 October 1956, Lohia wrote to his colleagues, discussing the importance of his proposed meeting with Ambedkar. He wrote the meeting would not only be significant for its political consequences, but also “a tribute to the fact that the backward and the scheduled castes can produce an intellect like him.” He also wrote to Ambedkar on the same day, asking him to take proper care of his health. On 5 October 1956, Ambedkar wrote to Lohia to schedule a time of their proposed meeting.

Ambedkar passed away on 6 December 1956, before the meeting could take place.

“You can well understand that my sorrow at Dr Ambedkar’s sudden death has been, and is, somewhat personal,” Lohia wrote to Limaye on 1 July 1957. “It had always been my ambition to draw him into our fold, not only organisationally but also in full ideological sense, and that moment seemed to be approaching.” Lohia added, “Dr Ambedkar was to me, a great man in Indian politics, and apart from Gandhiji, as great as the greatest of caste Hindus. This fact had always given me solace and confidence that the caste system of Hinduism could one day be destroyed.”

From the mid 1950s, Lohia followed what he called “principled politics.” He wanted to set his party apart by inculcating in its members a superior moral integrity. He enforced a strict code of conduct for everyone. Lohia wanted his party to be the opposite of the Congress—he wanted the party to be exclusively funded by the common people. It remained short of funds, but Lohia stuck to his principles in the face of adversity. The 1957 elections were again swept by the Congress.

“I would not bother if we came to power or not,” Lohia wrote in the party’s mouthpiece after the elections. “It would make no difference if we were beaten; we would continue on our path.” He wanted the party to be prepared to undertake a “hundred-year programme to fight injustice.”

Published in 1955, Lohia’s Wheels of History contained a description of that programme. He prescribed a concept of sapta kranti, or seven revolutions, which encapsulated his worldview. Lohia called for building a society based on economic equality; the abolition of caste; the emancipation of women; national independence; the elimination of colour discrimination; the individual’s freedom of thought; and freedom from coercion by collectives of any kind. Several of the ideas in the book were ahead of their time—for instance, that of an egalitarian world order without visas and passports, and with a common world parliament.

By 1960, even as he was becoming anxious about the Socialist Party’s failure to grow, Lohia continued to refine his views on oppression along the lines of class, caste and gender. In a letter that year to his partner, Rama Mitra, who was a literature professor, he wrote, “My conviction keeps on growing that an unequal treatment to women and tyranny over them have become so accepted in life, in fact so coordinated as to give rise to many appearances of beauty, that they also provide a basis and a habit for wrongs and tyrannies elsewhere.”

“Lohia problematised the gender issue in political terms and linked it with the other principle of segregation, that is, of caste,” Sheth told me. Like Sangh leaders, Lohia liked to invoke the Ramayana, but, according to Sheth, he was more interested in the “Sita-Shambuka axis,” reserving his affinity for the women and Shudra characters.

Around this time, Lohia began speaking of a 60-percent reservation in education and jobs for women, Adivasis, Shudras and Dalits. A slogan coined by his party’s stalwart Karpoori Thakur still resonates during elections in pockets of the Hindi heartland. “Sansapa ne bandhi gaanth, pichda pave sau me saath”—The socialists have taken a vow, backwards should get 60 out of 100.

In the third general election in 1962, Lohia fielded Sukho, a Dalit woman, against the Gwalior royal family’s Vijaya Raje Scindia, who represented the Congress. Lohia himself decided to contest against Nehru from the Phulpur constituency. The election results changed nothing at all. The Congress remained a dominant force, and Lohia’s party was reduced to just six seats in the parliament. Both Lohia and Sukho lost by big margins.

The media and liberal intelligentsia, both largely pro-Congress, panned Lohia, branding him a “cultural chauvinist” for his opposition to English. “His hatred and crude abuse of Nehru and his family is pathological,” a Times of India story said around the time. “His defeat in Phulpur is therefore a salutary verdict against noisy negativism in Indian politics.”

In a 2010 article for the Economic and Political Weekly, Yogendra Yadav wrote about how the Nehruvians and the Marxists—the two prevalent ideological camps of the intelligentsia at the time—“designed a wall of silence” around Lohia. Dismissal and rejection of Lohia without even reading him became common.

Some of this perception still survives. Yadav quoted the scholar Aijaz Ahmad’s introduction of Lohia to his readers in his 2002 book Lineages of the Present: Ideology and Politics in Contemporary South Asia: “Rammanohar Lohia … who had a visceral hatred of Nehru, had built a sizeable base for himself, especially in UP, with a combination of a broadly populist programme and extreme linguistic cultural chauvinism in support of Hindi as the national language.”

EVEN AS THE MAINSTREAM rejected Lohia, he was silently going about leaving an indelible mark on not just politics, but also on the country’s arts and culture. He saw how politics and culture went hand in hand.

Unlike the leftists, Sheth told me, Lohia had a deep understanding of India’s traditions and history. Lohia wrote on Ram, Shiva and Savitri, and was as passionate about the abused river Ganga as he was about the decline in politics.

It is a little-known fact that the painter MF Husain’s legendary series on the Ramayana and the Mahabharata was done at Lohia’s behest, after a meeting in Hyderabad. In his memoirs—MF Husain Ki Kahani, Apni Jubani—Husain talked about how Lohia once exhorted him to get beyond painting what hung in the drawing rooms of the Birlas and Tatas, and instead to paint the Ramayana, which Lohia considered the most interesting story of India.

Lohia’s words impacted Husain so much that within days of Lohia’s death, in 1967, he began work on the Ramayana series. Husain was given a room in the house of Badrivishal Pitti, Lohia’s friend and a member of the editorial board of the Socialist Party journal Mankind. A priest came every day to read out the Ramayana, as Husain painted. The artist created a hundred and fifty paintings all for free. “I merely respected what came out of Lohia’s mouth,” Husain wrote.

When I spoke to him, the Hindi writer Ashok Vajpeyi also acknowledged the influence of Lohia on his early writings. “He would write about complex subjects in the language of the street,” Vajpeyi told me. “He is the only politician whose contribution to intellectual India is highly undervalued.”

Vajpeyi recalled his first meeting with Lohia, in the early 1960s. Along with the writer Shrikant Verma and Kamlesh, the editor of the journal Jan, he had walked into the United Coffee House in Delhi’s Connaught Place, where Lohia was surrounded by a group of politicians. “He told everyone at the table to leave, since the intellectuals had arrived,” Vajpeyi said. “One man insisted he will stay back, but he was verbally pushed out. The man, I discovered, was Raj Narain”—the politician who, in 1975, won the famous electoral malpractice case against Indira Gandhi, after which she imposed the Emergency.

Vajpeyi said that Lohia loved to engage with artists and writers. He befriended and inspired writers in several languages—UR Ananthamurthy, Devanur Mahadeva, Raghuvir Sahay, Phanishwarnath Renu, Raghuvansh, BDN Shahi and Krishnanath, among others. When the modernist Hindi writer Gajanan Madhav Muktibodh was admitted to hospital with a serious illness, Lohia was among the few people who visited him. In 2010, the scholar Chandan Gowda wrote about Lohia’s influence on the Kannada literary tradition.

Lohia would go out of his way to indulge and encourage artists. The late painter J Swaminathan once landed up at Lohia’s Rakabganj Road residence in Delhi after his usual afternoon beer, only to find Lohia presiding over a party meeting. Swaminathan sent a note inside. Lohia called off the meeting, and spent the day with him.

Harris Wofford’s Lohia and America Meet and Rama Mitra’s Lohia Thru Letters show Lohia’s urge to reach out to the world. He corresponded with people such as Albert Einstein and the writer Pearl S Buck, and networked with some of the greatest minds of the time.

His interaction with writers and artists, Vajpeyi said, helped Lohia sharpen his own point of view. For instance, the Kannada writer UR Ananthamurthy used to quarrel with Lohia on the latter’s opposition to English. “After discussion with Ananthamurthy, Lohia realised that the cause of Hindi against English can be in camaraderie with other Indian languages,” Vajpeyi told me.

Lohia’s aversion to English culture also extended to the sport of cricket, which he dismissed as a relic of the Raj. But here, his public position seemed incongruent with personal interest. In his book A Corner of A Foreign Field, the historian Ramachandra Guha narrates an incident during the India–Pakistan Test series in 1960. Lohia was in Bombay, meeting journalists and supporters in an Irani cafe near Brabourne stadium. He attacked Nehru, English and cricket, and made a case for kabbadi. After the meeting, Lohia walked to a nearby paan shop, ate his paan and asked if Hanif Mohammad was still batting. Yes, he was told.

According to Yogendra Yadav, India’s Left politics has suffered due to a lack of politicians that deeply understand its traditions and cultural history. “Modi has come to power because the modern secular, liberal vision had no way to connect with the traditions of our country,” Yadav told me. “Their modernity is borrowed. Lohia was the first proponent of desi modernity. Lohia drew a distinction between cosmopolitanism and internationalism. To him, imitating the West is not modernity. Modernity is what India can produce.”

Lohia envisaged, Vajpeyi told me, a grand Ramayana Mela to celebrate the diverse social, cultural and political traditions of India. He planned readings and performances of multiple versions of the epic, including those where Ram was not the hero. “I am here with Raj Narain and others on way to Badrinath and the Ganga is flowing not too slowly right in front of me,” Lohia wrote in a 1961 letter from Haridwar to Rama Mitra, who was then in Germany. “I have been wondering why our nation is so bad at writing books. Surely, the Ganga is far richer material than any Nile or Amazon but no native Ludwig is born to tell the story”—a reference to Emil Ludwig’s The Nile: The Life Story of a River. Lohia’s trip was aimed at putting together the Ramayana Mela, which never came about.

Lohia’s relationship with Mitra, distilled from the numerous letters he wrote to her—at times three on a single day—was as open and unguarded as his politics. At the time, openly living with a person without marriage, as Lohia and Mitra did, required courage and conviction. Passion defined both his politics and personal life. His letters to Mitra reveal a man madly in love, who traversed multiple worlds with her, threw lover’s tantrums, rebuked his beloved, stressed about her illness, worried about her PhD and her political education and taught her history. Like an enamoured adolescent, he was always making detailed plans to steal a few precious moments with her amid his hectic political life. The letters reveal a Lohia who was not beyond human frailties. He was jealous and insecure in love, called his beloved by several endearments, bought footwear for her on foreign trips, meticulously arranged for a mixture of cardamom and cloves to be sent to her in Germany and thanked her for the cologne she bought for him. When he felt scorned, his words even showed traces of misogyny.

Lohia’s pet peeve in the majority of his letters was Mitra’s nonchalance about the meticulous minute-to-minute programme he would plan in advance so that they could spend time together. Asking her to come to Sarnath, Lohia wrote, “Dear Ela, the Banaras programme is on 10th and 11th April. Intend to stay in a Sarnath Hotel. 12th April will be wholly unengaged. Even the evenings of 10th and 11th will be free … please try to make both possible.” Mitra’s failure to meet his exacting plans rendered him temperamental. “Dear Ellurani, I sent you a telegram on the night of 12th. I got your letter on 13th. I got to know about you three days after you were to reach Gorakhpur. This is not fair. What has been decided should be followed. You did not follow the programme or informed me. Not even a telegram. For three days I kept imagining one or other mishap has taken place. If I stop trusting you, it would not be good.” Following the requisite admonition, he asked her to make it to Mirzapur without fail.

“I have been wondering why our nation is so bad at writing books. Surely, the Ganga is richer material than any Nile or Amazon but no native Ludwig is born to tell the story”

The letters also allude to Lohia’s insecurity about losing Mitra. In one of the letters, he was upset that she had made plans with someone else. “When you make plans with someone, you have no right to make plan with others at the same time,” he wrote. “Please tell me should anyone come to receive you at the port. If I am there, you would have to come with me and also accompany me to Elephanta.” Thereafter, he raised the crucial question: “I do not like the story of your many lovers. But if you tell me the entire story then I might be able to take it as an epochal story … It would be better if you get married but it is not fair that you keep talking about him.” Next, Lohia rebuked Mitra—still in Germany—for asking if he missed her. “And stop using your women’s tricks on me about whether I miss your letters or not.”

The letters, mostly from the early 1960s, show Lohia at his most unguarded. While they exhibit his love for Mitra, they also reveal Lohia’s dissatisfaction at the time with his political career. “However much there might be pain in the heart, in fact, more so because it is there, one has to do one’s duty,” he wrote. “The battle for the Socialist Party must continue.”

At one point, with considerable self-deprecation, he talked of his failure as a politician. At times Lohia would turn melancholic about politics in general and why he did not succeed. In a letter demanding cologne from Mitra, Lohia began with an admission that he “was not fated to be a politician or even a writer.”

In another letter, which began with how sending her telegrams did not satisfy him, Lohia was aggrieved with the meagre donations to his party. “I am more or less definite now that sharks, mice and tortoise alone are fit for politics,” he wrote. “And yet politics is religion of the short run just as religion is politics of the long run—both the highest virtues of mankind.”

AFTER THE DEFEAT IN 1962, Lohia began setting afoot plans that would change the course of Indian politics. Until the 1960s, he had been shunning alliances over the tiniest of ideological disputes. But, after the third general election, Lohia realised that it was not possible for any single party to beat the Congress on its own. Elections seemed to be a formality to return the Congress to power. The ruling party’s hold over the administration and every institution of the country ensured that no anti-government narrative held any sway.

“The prospect of indefinite Congress rule and the perpetuation of Nehru dynasty made Lohia restless,” Limaye wrote. “And he began to explore new pathways.” In statements to newspapers after the election, Lohia speculated that merging some of the existing political parties might lead to a party capable of defeating the Congress.

He praised the mild success of the communists and the Jan Sangh in the 1962 polls, calling them “parties of upheaval.” He began reaching out to political opponents—such as the communists, the Praja Socialist Party, the Jan Sangh, and the Swatantra Party, an avowedly secular right-wing party founded by C Rajagopalachari—to figure out methods of cooperation.

According to Limaye, “Lohia desired to create a new party into which he would integrate partial ‘revolutionary fervor’ of the communists and the ‘vigour’ of the Jan Sangh’s nationalism—which was albeit ‘restrictive.’”

This was a significant change in Lohia’s outlook, considering that he had for a long time consistenly described the Jan Sangh as communal and unethical. “The Jan Sangh is sectarian in outlook but cleverer than the Swatantraites or the Communists,” he had written in an issue of Jan during the 1960s. “It has imbibed all the virtues and vices of reactionary Hinduism; there is no consistency in their character, speech, action and policy; but they have successfully held together and have learnt the art of alternately using this group or that in order to increase their own strength. Narrow sectarianism, [the slogan of] ‘undivided India, cultural unity and democracy’ in speech and short term selfishness in action, this has been the hall mark of Jan Sangh policy.”

Lohia decided that the only way to defeat the Congress was to pool the opposition vote through pre-poll alliances, a strategy he named non-Congressism. It was first tested in the 1963 bypolls for the four Lok Sabha seats of Rajkot in Gujarat, and Amroha, Jaunpur and Farrukhabad in Uttar Pradesh. The seats were respectively contested by Minoo Masani of the Swatantra Party, JB Kripalani of the Praja Socialist Party, Deen Dayal Upadhyaya of the Jan Sangh and Lohia himself. The four parties fought the polls together, and Masani, Kripalani and Lohia won. This was the first sign that the Congress’s dominance was nearing its end.

According to Madhu Limaye, “Lohia desired to create a new party into which he would integrate partial ‘revolutionary fervor’ of the communists and the ‘vigour’ of the Jan Sangh’s nationalism—which was albeit ‘restrictive.’”

In 1964, Lohia worked to unite the socialists and organised a merger with the Praja Socialist Party to form the Samyukta Socialist Party. (A breakaway faction, however, revived the PSP later that year.)

In 1966, Limaye wrote in The Birth of Non-Congressism, Lohia launched a three-pronged attack on the Congress: “collective mass action and fighting for civil liberties through the courts; exposure of the government’s misdeeds in parliament and the state legislatures; and efforts to work out electoral no-contest agreements.” As Limaye recorded, Lohia was conscious that such alliances cannot be “all take and no give.” He went out of his way to make concessions for other parties. In his efforts to unite the SSP, the communists, the Jan Sangh and the Swatantra Party, he proposed a series of seminars to plan a governmental programme to examine policy issues in depth.

Lohia’s idea was not met with enthusiasm. The Jan Sangh wanted the seminars to be held under the banner of a non-political group. P Sundarayya of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) said he would have to seek the opinion of the politburo. SA Dange of the Communist Party of India was willing, and NG Goray of the PSP wanted the seminars to be closed-door events. A seminar, called “The Political Alternatives in India,” took place in early 1967, but it could not evolve any consensus. It became clear that there were severe ideological differences among the participants. For instance, the Swatantra Party and the Jan Sangh wanted nothing to do with the communists, while the communists were united in their opposition to the Jan Sangh and the Congress.

Lohia exhorted them to maintain their separate organisational and political identities, but if they were to fight an election together, he argued, they needed to agree on some “concrete governmental and legislative programmes for the achievement of some definitive aims.”

As the 1967 election drew near, no mahagathbandhan could be seen. Eventually, state-level alliances were made. The Jan Sangh decided to go it alone in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Maharashtra. In Kerala, a united Left Front fought together with the SSP and the Indian Union Muslim League. In Bengal, the CPI allied with Ajoy Mukherjee’s Bangla Congress and the PSP. A loose understanding was reached in Rajasthan as well.

When the result came, it was a shock to many opposition leaders, who did not share Lohia’s certainty that the Congress could be shaken. Though Lohia barely scraped through himself in Kannauj, defeating SN Misra of the Congress by 472 votes, his SSP won 23 seats, performing especially well in the assembly elections in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. The Congress failed to get a majority in Bihar, necessitating a coalition government. Sworn enemies such as the CPI and the Jan Sangh joined the SSP to form the government under the aegis of the Samyukta Vidhayak Dal.

In Bihar, Lohia’s mobilisation of the Other Backward Classes finally paid dividends. Although the new chief minister, Mahamaya Prasad Sinha, was a Kayastha, the man appointed deputy chief minister was Karpoori Thakur, who belonged to the backward nai—barber—community. Thakur was among Lohia’s closest aides, and the two had known each other since the days of the Congress Socialist Party.

The 1967 election marked the first time that India truly became a multi-party democracy. Lohia’s mobilisation of Shudras and regional identity groups was a success, making Indian politics more and diverse. The Congress managed to retain its majority, with 283 seats out of 520 in the Lok Sabha, but its overall performance gave the first sign of the disintegration of the monolith. In the simultaneous assembly elections, regional parties such as the Akali Dal in Punjab, the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam in Tamil Nadu, the Bangla Congress and the Forward Bloc in West Bengal, the Jana Congress in Orissa and Madhya Pradesh, the Jana Kranti Dal in Bihar, the IUML in Kerala and the Peasants and Workers Party in Maharashtra made their mark.

The election left Lohia with high hopes. He said that “the end of the age of greed, corruption and licentiousness is within sight.” What was to begin, according to him, was the “age of simplicity and duty.”

He was wrong. It did not take long for the 1967 experiment to fall apart. Lohia was disheartened to see how quickly the taste of power transformed many of his comrades in Bihar. Ministers surrounded themselves with the trappings of power.

Lohia continued advising the SVD governments, and pressed for the delivery of agreed initiatives. The Bihar government carried out a half-baked abolition of land tax on profitless agriculture, curtailed the use of English in public places, and undertook initiatives to deal with famine and corruption. However, other than spewing anti-Congressism, socialists in power proved no different to their Congress predecessors. The greed of the SSP leaders and Lohia’s demands for principled conduct became locked in a constant struggle.

The most significant dispute involved Bindeshwari Prasad Mandal. Mandal had won a seat in the Lok Sabha in the 1967 election, but wanted to give it up and become a minister in the SVD government. Lohia was furious, and tried all he could to make Mandal take the Lok Sabha seat. He asked Limaye, who had just become party president, to convince Mandal to give up the job of state minister. Mandal demanded a front seat in parliament, a bungalow and chairmanship of a parliamentary committee. Limaye agreed to the conditions. Yet Mandal did not resign.

The election left Lohia with high hopes. He said that “the end of the age of greed, corruption and licentiousness is within sight.” What was to begin, according to him, was the “age of simplicity and duty.”

“He had deserted the Congress to join the SSP but it seemed his ideological roots were still intact,” Limaye wrote. He added that Mandal and many SSP men broke up into caste groups. “They equated the policy”—Lohia’s anti-caste doctrine—“with casteism!”

On 30 September that year, Lohia was operated upon for an enlarged prostate gland. After struggling with post-operation complications, he passed away, on 12 October 1967.

It was not long before Mandal brought down the Bihar government with Congress support, by defecting along with 40 legislators. He dismissed Lohia’s ideology as “Marwari socialism.” Soon, SVD governments in other states began to collapse.

Limaye attributed the fall of the SVD governments to Lohia’s inability to make room for weaknesses. “Sometimes his approach was not practical,” he wrote. “He did not make allowance for the human material with which one has to work in India.”

A fragmented opposition without a credible leader at its helm helped the Congress come back with a massive majority in the 1971 general election.

{THREE}

DESPITE ITS APPARENT FAILURE, the 1967 experiment had major implications for the country’s politics.

This was the start of the coalition era, which also gave rise to the culture of defection. The aaya ram, gaya ram leaders—floor-crossing politicians, named after Gaya Lal, a Haryana legislator who defected from the Congress to the United Front and back to the Congress within a single fortnight in 1967—became a phenomenon, fostering a culture of corruption. Even after an anti-defection law was enacted during Rajiv Gandhi’s tenure, the culture reinvented itself. It persists even today.

While non-Congressism lost credibility for some time, it came back stronger after the Emergency. In the 1977 general election, an amalgamation of parties, as Lohia had imagined, took the form of the Janata Party—a fusion of Congress rebels, socialists, secular right-wingers and the Jan Sangh. However, the Janata government, too, fell apart within a few years, for reasons including corruption, poor economic performance and severe ideological disputes between the secular members and the Jan Sangh leaders Atal Bihari Vajpayee and LK Advani.

When the leadership of the Janata Party banned members from having dual membership of the party and the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh, the Jan Sangh leaders left to create a new party, which they called the Bharatiya Janata Party. Its leaders soon developed a janus-faced politics—according to convenience, they could either invoke their modern Janata Party lineage, or adopt a hardline Hindutva. Over the years, the BJP has come to reap the fruits of Lohia’s non-Congressism—under Vajpayee, it led the only non-Congress government to date to complete five years in power, and, under Narendra Modi, it became the first non-Congress party to win a simple majority in parliament.

“In a sense Lohia legitimised the Jan Sangh,” Sitaram Yechury told me. “Except for Lalu Prasad’s RJD, socialists of all hues have done business with Jana Sangh and BJP. We did not.” Yechury remembered to add as a caveat that the CPI too supported the coalition government in Bihar in 1967, which included the Jan Sangh. But he did not mention his party’s support to the VP Singh government, which was also supported by the BJP.

The kind of criticism Lohia levelled at the Congress of the 1960s is now applicable to the BJP, which poses a similar threat to Indian democracy. If one looks at Lohia’s view of their ideologies, he was perhaps as averse to the Jan Sangh’s ideology as he was to that of the Congress, if not more.

The socialists disintegrated in the coalition era. Socialist parties broke up into several regional forces that mobilised particular castes. It would be a decade and a half after Lohia’s death that his avowed acolytes would take centrestage in Indian politics, removing its Brahminical sheen. The OBC and Dalit assertion in north Indian politics owes a lot to Lohia. However, these claimed legatees of Lohia seem completely divorced from the ideas, principles and political culture he embodied.

Supposed followers such as Mulayam Singh—whom Lohia fielded from Jaswantnagar in 1967—and Lalu Prasad Yadav, among others, claim allegiance to Lohia by putting his portraits in their offices and election posters, and mouthing Lohia-isms whenever convenient. Lohia, however, would not have stood for the manner in which his idea of a political coalition among the socially discriminated, economically exploited and culturally marginalised has been distorted into the form of today’s caste politics. To say nothing of the normalisation of corruption and crime under their governments.

According to Ashok Vajpeyi, Lohia inherited “Gandhi’s dream, Nehru’s desire and Subhash Bose’s action.” Lohia’s main ideas—daam baandho (fix prices), jaati todo (break caste), varg sangharsh-varn sangharsh (class struggle-caste struggle)—are as relevant now as they were during his time. All these ideas need now are followers.

ON 23 DECEMBER 2018, Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressed the BJP’s booth-level workers in Tamil Nadu via video conferencing. He was supposed to talk about the achievements of his government, but Modi spent a significant amount of time attacking the efforts by political parties to build a mahagathbandhan for 2019.

“Today, several leaders are talking about a grand alliance or mahagathbandhan,” Modi said. “Several of these parties and their leaders claim to be deeply inspired by Dr Ram Manohar Lohia, who was deeply opposed to the Congress, and the way Congress did politics. What sort of a tribute are they paying to Dr Lohia by forming an unholy and opportunist alliance with the Congress?”

Modi added that Mulayam Singh Yadav had forgotten how the Congress harassed him by slapping cases against him. “Have these parties done justice to the ideals of Dr Lohia?” he asked. “The answer is a resounding ‘no, no, no!’”

He then went on to talk about the history of conflict between the Congress and several parties that are supporting the mahagathbandhan, such as the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, the Telugu Desam Party and the Nationalist Congress Party. “The truth is this so-called grand alliance is a club of rich dynasties,” he said. “They are only to promise family rule.”

Modi’s attack on the mahagathbandhan comes across as completely ignorant of his own party’s history. Rallying around the doctrine of non-Congressism, the BJP, like its forerunner, has struck alliances with several parties opposed to its ideology. After the 1960s, when they partnered up with Lohiaite socialists, communists and secular rightists in the SVD governments, there has hardly been an election where the BJP has not partnered with an ideological opponent. Like Yechury, Modi also seems to have conveniently forgotten the support provided to the VP Singh government by both the BJP and the CPI(M).

Modi’s assessment of what Lohia would have done in contemporary times also seems like a wilful misinterpretation. Lohia’s prescription to uproot the Congress does not apply, because the Congress has already been uprooted. The kind of criticism Lohia levelled at the Congress of the 1960s is now applicable to the BJP, which poses a similar threat to Indian democracy. If one looks at Lohia’s view of their ideologies, he was as averse to the Jan Sangh’s worldview as he was to that of the Congress, if not more.

“As electoral tactic, he would have been part of the non-BJPism of today’s context,” Yogendra Yadav told me. “But Lohia would have looked beyond 2019, and not looked at alliance as electoral tactic alone. In terms of policy, Lohia was the architect of social justice.” But, Yadav added, “These policies have not been incorporated into mainstream politics. Lohia’s insistence that the energies of lower strata of society, including women, are unutilised is his deep legacy that needs to be responded to.”

The BJP was the biggest beneficiary of non-Congressism. Who might benefit from the non-BJPism of this election is not quite clear yet. But Modi’s attack on the mahagathbandhan seems to suggest that he, too, understands the threat is real. If it works out, an alliance between the SP, BSP and Congress in Uttar Pradesh might just be the BJP’s undoing.

During my interview with Akhilesh Yadav, he insisted that his party was committed to follow the path set by Lohia. “In 2019, the SP is going to have a threefold role as the opposition,” he said. “First, we are going to fulfill Dr Lohia sahib’s dream by coming together with the BSP”—a reference to Lohia’s correspondence with Ambedkar. “Second, we are going to bust this new ‘Modi myth,’ and third, we are going to be the symbol of unity by showing large-heartedness in our decisions. We shall stitch together an opposition that will enmesh the BJP.”

Yet, Modi may be right in that these parties have failed to learn from Lohia. When Lohia tried to build a mahagathbandhan, he was ready to compromise over electoral adjustments, and worked to formulate policy goals for the government he was trying to bring into being. Today’s opposition has no common constructive aims besides taking down the BJP, and the frictions among possible partners do not look like they will be resolved.

Perhaps the most important lesson from the Lohia story comes not from where he succeeded, but where he seemingly failed. As Limaye said, Lohia did not often “make allowances” for weaknesses. The mahagathbandhan leaders must figure out a way to deal with human greed, not only that of others, but also their own.

AKSHAYA MUKUL is an independent researcher and journalist. He is the author of Gita Press and the Making of Hindu India. He is currently working on the first English biography of the Hindi writer Agyeya.

HindutvaalliancepoliticscoalitionsCoalitionBJPRammanohar LohiaElections 2019Bharatiya Janata PartyRam Manohar LohiaOppositionseat-sharingMulayam Singh Yadav

On Ram Manohar Lohia’s death anniversary, what lessons can the struggling Opposition learn from him?

The socialist leader offers a way to forge a unified front and an alternative to the BJP’s cultural nationalism.

Oct 12, 2022 · 07:30 am

Since politician Ram Manohar Lohia died on this day 55 years ago, Indian politics has taken a course fundamentally different from his vision for the country.

Born on March 23, 1910, in Akbarpur in Uttar Pradesh, Lohia went on to write his doctoral thesis on the national economy at the Humboldt University of Berlin between 1929-’33, before returning to India to plunge into the freedom struggle.

After Independence, Lohia led factions of the Socialist Party of India and formulated his own variant of socialist philosophy. He soon emerged as one of the most articulate spokespersons of India’s political Opposition before his death on October 12, 1967.

Are there any lessons for today’s struggling Opposition to learn from Lohia?

Ideology and alliances

With the next Lok Sabha elections due in 2024, the first cue the Opposition can take from Lohia is unity. While Lohia was opposed to coalitions, after the return of the Congress with a majority for the third time in 1962, he felt that only by uniting would the Opposition have some hope of succeeding.

The Opposition today already appears to be making such an effort, but Lohia could help it bridge two crucial gaps through which current attempts at unity are slipping.

First is the charge of ideological compromise. Like Lohia, today’s Opposition too faces this accusation. Lohia’s approach could help the Opposition evolve a confident response to critics, by placing the ideological question more reasonably in the hierarchy of issues faced by India. Lohia was aware that the Opposition parties, like today, were too weak to single-handedly impose their ideologies. Besides, he seemed to have realised that ideologically opposed parties would keep each other in check.

The other gap is that many parties looking to forge a nationwide alliance are opposed to sharing space with prospective allies in their own boroughs. Symptomatic of this problem are the Indian National Lok Dal or Telangana Rashtra Samithi talking of unity without the Congress, or the Trinamool Congress’s refusal to join hands with the Left parties in West Bengal. They could learn from Lohia, whose Socialist Party united with the Jana Sangh and Communists despite the three parties eyeing the same non-Congress space.

Social coalition

If the brute majority of the Congress was to be countered by uniting all parties, Lohia wanted to challenge dominant groups too by advocating a broad social coalition. His coalition included Dalits, Other Backward Cases, Muslims, women and backward castes within minority groups. He also included the upper-caste poor, whom he labelled as “false high castes”.

The Opposition parties have often been cornered by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party into choosing between polarising alternatives – from issues of caste and social justice to religion.

They frequently have to grapple with advocating social justice for Dalits or articulating the anxieties of the upper-caste poor, to siding with Muslims or Muslim women’s rights. Do they voice the identity concerns of the dominant ethnic communities in the North Eastern states or talk of the vulnerable position of Muslim minorities there? Building a broad social coalition could be the Opposition’s best bet to dent the Hindu consolidation shored up by the BJP.

Cultural politics

Lohia also offers interesting possibilities to evolve an alternate cultural politics. Religion is one of the fundamental planks of the BJP’s cultural politics and a difficult terrain for the Opposition. While Lohia would have agreed with the Opposition that political parties should not weaponise religion to create strife, his approach to the broader question of the relationship between politics and religion was more nuanced.

Neither did Lohia advocate a complete negation of religion – like some progressives – and nor did he share typically liberal prescriptions of keeping it separate from the state or equal treatment by the latter.

Instead, Lohia felt politics could never be unconcerned by religion. He suggested that politics take an exploratory attitude towards religion and inculcate messages of an ethical life, compassion and contemplation. In a deeply religious polity like India, this could be the basis of developing a more effective bulwark to communalism.

The BJP’s other key plank is cultural nationalism. Against the BJP’s exclusivist thrust, the Opposition has posed alternatives from pluralistic to developmental nationalism. Lohia may have also emphasised India’s common cultural heritage. In fact, he painstakingly tried to corroborate the country’s shared cultural roots by demonstrating similarities in monuments and letters of the alphabet in various parts of India.

While this might appear similar to what the BJP does, Lohia’s cultural nationalism is not revivalist. For the past is not accorded an unquestionable priority, nor was it exclusive. This is because instead of being rooted in a communal identity, Lohia’s cultural nationalism included all those who entered the fold of Indian civilisation.

A matter of ethics

Finally, the Opposition could benefit greatly by inculcating the socialist leader’s commitment to ethical politics. When the BJP stormed to power in 2014, the Indian electorate saw it as a more credible alternative.

With the Congress heading for a much-hyped internal “democratic election”, even though the democratic credentials are itself in doubt, how far does it conform to Lohia’s dictum of having an honest political policy? As another example, it does not take much to realise where Opposition leaders who accuse the BJP of extravagance (“Suit Boot Ki Sarkar”) may themselves stand on Lohia’s call for altruism and restraint.

It will take much more than cold calculations to enable the Opposition to effectively take on the BJP’s vast, committed cadre. The Opposition can only regain trust when it manages to project itself as a genuine alternative through sincere and committed involvement with its agenda.

But this is undone by Opposition members effortlessly switching sides with bitter critics becoming the most vocal spokespersons for the ruling dispensation overnight. Perhaps, the biggest cue the Opposition and its leaders can take from Lohia is his commitment to a politics of truth.

October 12 is Ram Manohar Lohia’s 55th death anniversary.

The writer is a doctoral student at the Centre for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

Remembering Ram Manohar Lohia’s Uncompromising Fight for Gender Justice

The woman, he believed, is a more committed agent of civil resistance than her male counterpart.

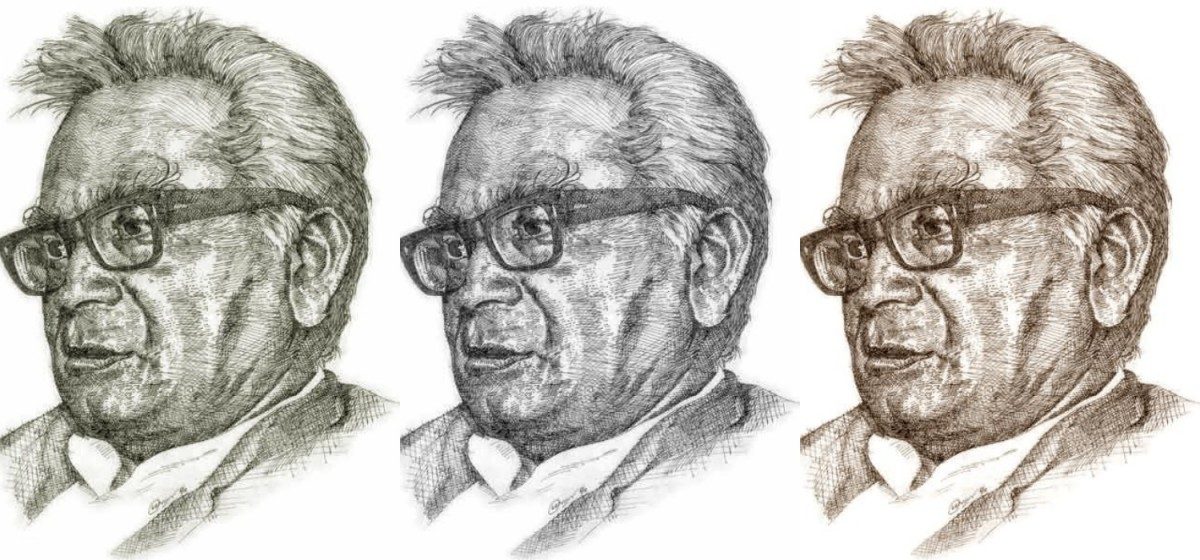

Ram Manohar Lohia. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

CASTEGENDERRIGHTSWOMEN23/MAR/2019

Throughout his life, Ram Manohar Lohia fought an uncompromising battle for social equality. Central to this fight was the issue of equality between men and women. At a time when few of his contemporaries engaged with issues of gender, Lohia offered hope. He raised the issue of gender justice consistently and forcefully – thereby redefining the socialist agenda.

He considered the “segregation of caste and sex” to be the worst form of discrimination. He recognised women as one of the most exploited sections of society. Gender discrimination, affecting half of the world’s population, is as distinct as it is pervasive – across castes, classes, cultures, countries and civilisations. Lohia asserted that class and caste oppression may be specific to countries, but the oppression of women is ubiquitous.

Lohia claimed that the modern economy and class equality would not eradicate caste and gender inequality. He recognised these to be specific and autonomous forms of discrimination which needed to be addressed independently. He, however, did not view them in totally exclusive terms. “All war on poverty is a sham, unless it is, at the same time, a conscious and sustained war on these two segregations,” he said.

If democracy and socialism are battles for equality, then the issue of gender should be placed at the core of such agendas. Charting out “seven revolutions” to realise social equality in the world, he considered gender equality to be at par with caste and class equality, national revolution, ending imperialism and protecting individual privacy.

Also read: From Farms to Slums, the Job Crisis Has Left Women Even More Vulnerable

Lohia believed that real success for socialist politics will be achieved only when segregation between men and women ends. This is what separated him from other socialists and Marxists – who either did not give specific attention to gender and caste inequality or prioritised issues of class over other forms of discrimination.

Reflecting on the everyday plight of women in India, Lohia highlighted some of its dimensions. He expressed disgust for dowry, pointing out how it leads to denying women proper education – more dowry needs to be paid for educated brides. He criticised extravagant weddings, deeming them vulgar and burdensome to parents of brides. This, in turn, promoted a preference for male children, he claimed.

Ram Manohar Lohia. Credit: lohiaphotos.blogspot.com

Lohia was against arranged marriage as well. He said it is not the parents’ responsibility to get their son or daughter married. Their responsibility, he stressed, ends with providing a good education and good health. Adults should choose their own partners, exercising individual choice.

He was concerned about the humiliation endured by widows and single women. He spoke of the stigma attached to widowhood, saying backward castes are not as ruthless in their treatment of widows as higher castes are.

Contradicting socially defined roles, Lohia opposed confining women to the kitchen and restricting their utility to fetching water and fuel. He opposed the culture mandating that women are to eat after serving others. This, he argued, left eight out of 11 women hungry. The suffering was worse for women from poor families, where food can be scarce.

Also read: George Fernandes: The Descent from Idealism to Vanity

When Lohia visited someone’s house for a meal, he always insisted that the women must sit with others. At times, he used to survey the kitchen to see if there was enough food for the family.

Lastly, Lohia wrote at length on the “tyranny of skin colour” and society’s obsession with fair skin. He said that equating beauty with fair skin is discriminatory and leads darker women to suffer social stigma, neglect and ill-treatment within their family. He argued that colonisation by white imperialists was responsible for the culture of privileging fair skin. If African nations had ruled the world, standards of female beauty would undoubtedly have been different, argued Lohia.

He criticised the market for reinforcing this “tyranny” by selling soaps, creams, lotions and other cosmetic products which promised fairer skin.

To establish gender equality, Lohia argued for preferential treatment, not equal opportunities. He was of the firm belief that equal treatment in an unequal society would only perpetuate existing inequalities. Ahead of his time, he demanded reservation for women– alongside other backward classes – in government jobs and in institutions of higher learning.

Lohia argued that women from marginalised castes should be given 60% reservation. Despite being 90% of the population, he said, these backward groups do not occupy more than 5 to 10% of high positions in any sector. Only by harnessing the energy and capability of women can the nation flourish, he believed.

He declared, ‘The moral well-being of the nation can be gauged by its women, and the women of the so-called depressed classes at that.”

As a matter of practice, he advocated women’s participation in socialist parties as members, leaders and party functionaries. Launching the Socialist Party in 1952, Lohia specifically underlined the need for the increased participation of women in active politics.

Lohia believed that greater women’s representation would minimise political violence. The woman, he said, is a more committed agent of civil resistance than her male counterpart.

Many of Lohia’s observations on gender issues were ahead of his time. His argument for preferential treatment for women came much before the reservation in the panchayati raj system was implemented.

The best tribute that can be paid to Lohia on his birth anniversary would be to retrieve his ideal of ensuring a greater participation of women in public life, politics and civil disobedience movements.

Richa Singh is former president, students’ union, University of Allahabad. She belongs to the Samajwadi Party.

Do you know the feminist Lohia?

He dreamt of a coalition of the backward castes, Adivasis, minorities, working class and women which would unitedly oppose all the different axes of power – caste, class, race, gender – and usher in a new world

Lalitha Dhara March 21, 2017

23 MARCH: LOHIA JAYANTI

Dr Ram Manohar Lohia (23 March 1910 – 12 October 1967) occupies prime place among the ignited and charged minds of 20th-century India. He was a non-conformist, rational and sensitive human being. Equally, he was a profound, innovative and brilliant thinker. He dreamt of a society based on democracy, socialism, justice and peace. He visualized a world without borders and barriers. He was, simultaneously, a fierce nationalist and a global citizen, without contradiction.

Lohia’s father, Heera Lal, who was an ardent follower of Mahatma Gandhi, introduced the freedom struggle to him when he was barely in his teens. This left a deep mark on young Lohia. After his return in the early 1930s from Germany, where he obtained his doctorate, he plunged into politics. He started his political career with the Congress but started charting his own path through the 1940s and the 1950s, experimenting with different political formations, collecting fans and followers, along the way. By the mid-1950s, he had given shape and structure to his concept of an ideal society and the path towards it.

Lohia dreamt of a decentralized socialist State that could be realized through electoral means. He wanted to fuse elements of Marxism and Gandhism to come up with a uniquely Indian model of socialism – authentic, rooted in Indian social reality and reflecting the Indian ethos. Here again he wanted to distinguish his brand of Socialism from the Nehruvian model of State-supported socialism on the one hand and from the Indian communist model of centralized Socialism on the other. In contrast to both, he preferred a decentralized economic and political model. He didn’t confine his ideas to the economic realm, when it came to change. He was all for overhauling the social and the cultural structures as much as the economic and the political structures. He even included racism and dominance of language as enemies to be confronted. As for caste and gender stratification, he felt they owed their origin and history to one and the same ideology, which we recognize today as brahmanical patriarchy. He critiqued both institutions and drew linkages between them in his seminal essay, “The two segregations of caste and sex”. In so doing, he joined the league of other great social revolutionaries such as Phule, Ambedkar, Periyar and Shahu.

Lohia’s canvas was vast, crossing national and geographic boundaries. He wanted inequalities between nations, within nations and between castes, classes, sexes, races and communities to end. Like Phule who talked of the Shudras, Atishudras and women coming together, Lohia too dreamt of a coalition of the backward castes, Adivasis, minorities, working class and women which would unitedly oppose all the different axes of power – caste, class, race, gender – and usher in a new world. Through his radical ideas and inspiring leadership, Lohia enthused and goaded his followers into action, during the 1950s and 1960s, leading from the front. He was aggressive and non-compromising in attaining his target but did not leave the path of Satyagraha, even momentarily.

For Lohia, personal ethics was as important as social and political ethics. This was what made him honest and transparent – something so very rare among political leaders of all hues. He always spoke and acted with courage of conviction. One instance is from when his party (Praja Socialist Party) was in power in the State of Travancore-Cochin (now part of Kerala) and was faced with an agitation by estate workers. The government of the day resorted to firing. Lohia could not condone this act of the government headed by his own party. He demanded their resignation. This led to his ouster from the party. In his personal life too, there was no contradiction between his principles and practice. He nurtured his personal relationships in full public glare, unmindful of the consequences. He did not believe in the institution of marriage and so remained unmarried all his life. He did not believe in accumulating wealth. True to his belief, he left behind no progeny, property or bank balance when he died.

Dr Lohia was one of a rare breed of leaders of 20th-century India who gave a serious thought to the gender question. He believed that gender revolution was a necessary precursor for a general revolution. His views on sexuality, chastity, virginity and morality were refreshingly unorthodox and he condemned the double-speak on them. To him, the central issue was the dignity of women, not their so-called purity or morality, and he regarded work as central to women’s dignity.

He condemned female infanticide, dowry system and blamed it on the patriarchal mindset that, he argued, could be displayed by both men as well as women. He wanted this mindset to be ruthlessly and systematically “ferreted out and destroyed”. Every word of every sentence that Lohia uttered on the “gender question” comes with the force of a guided missile, across space and time, to dent the core of patriarchal ideology. He understood, only too well, that patriarchy is a many-headed monster and needs to be attacked from all sides!

What comes through, touchingly, from Lohia’s speeches and writings is the immense and intense love, respect, regard and concern he had for women. He waxed eloquent about the beauty of women – whether dark-skinned or fair, low-caste or high-caste, a labourer or otherwise. He did not see women as empty beauties. Rather, he saw them as productive beings – within the home and without.

Venturing into the realm of mythology, Lohia narrates the story of Shiva and Parvati, in which they dance together, matching steps in competition, as it were. Suddenly, Shiva lifts a leg high above the ground. Parvati, with all the modesty expected of a woman (goddesses being no exception), is unable to match his step. “When Siva made that gesture of vigour, was it to clinch the issue and gain a victory in an encounter that was going against him?” Lohia wonders (see Lohia’s essay, ‘Rama and Krishna and Shiva’), clearly implying the earliest manifestation of patriarchal power relations.

He gives a contrary picture of Shiva in the following story. “… When a devotee had refused to worship Parvati alongside him, Shiva took on the shape of the Ardhanarishwar, half-man half-woman.” Lohia is perhaps trying to tell us that all human beings are a blend of the male and female and that the potential for equality in the relation between the sexes is ever present.

He idealized the fiery, witty, dark-skinned Draupadi over the submissive Savitri or the demure Sita of Indian mythology and said rhetorically, “If the myth of Savitri exists, please mention another parallel one where a devout husband brought back his wife from the dead, rescuing her from the clutches of Yama.” (See Lohia’s essay, “Draupadi or Savitri”)

In a brilliant treatise on the myths of Ram and Krishna and Shiva, he talks of a Ram who represents a life of limits, a Krishna who is ever exuberant and a Shiva who is seamless. He expresses concern that followers of Ram could degenerate into wife-banishers while those of Krishna into philanderers in a patriarchal set-up. He wanted to enlarge the ideal of Ram-Rajyato Sita-Ram-Rajya!

Lohia himself sought to combine the best qualities of the three mythical heroes. Like Ram, he contained his actions, agitations within the norms and boundaries of democratic and legal means available under the Constitution. In the realm of ideas, however, he soared without restraint much like Shiva (for example, he envisaged a world without passports and visas!). Whether engaged in thought or action, he did both with an exuberance that is infectious, very Krishna-like! I would like to venture that he was a true Ardhanarishwara, as his feminine and masculine sides were well balanced and he was in tune with both. That is how he could understand and empathize with the everyday micro-level problems faced by women – like smoking chulhas, lack of toilets, having to fetch water from afar, etc – while applying his mind to global issues.

Lohia romanced India. He worshipped its diversity, plurality and found an underlying unity in its arts, architecture and sculpture. His writing, “Meaning in stone”, is a beautiful, evocative piece and reveals the connoisseur in him. “The Indian people have chiselled their religion and history in stone,” he observes. “Between history and art, there is, in India, a deep alliance. Where history goes, there art precedes or follows.” He ends his essay with the words: “To create is to live in freedom and with vigour.” He comes through as a man with a deep sense of history who is intensely conscious and proud of his heritage.

He interacted with writers, painters and profoundly influenced them and was influenced by them. M.F. Husain, a close friend of Lohia’s, admitted as much when he spoke about the latter being the inspiration behind his ‘Epic’ paintings. So have many modern and progressive writers like P. Lankesh, U. R. Anantamurthy and Tejasvi, who have written prolifically in Kannada, spurred on by Lohia’s ideas and dreams.

When it came to personal relationships, he was very sensitive and perceptive and felt that man-woman relationships were delicate and needed to be nurtured honestly and sincerely. He shunned hypocrisy in relationships and argued for transparency, putting the onus on both parties. He would stress on mutuality in a relationship. He idealized the relationship between Draupadi and Krishna as one of utmost companionship!

Lohia’s dreams were not merely about ending oppression and exploitation but also about well-being and individual and collective happiness, where each individual could bloom and flower, resulting in a happy society. His USP lay in the way he sought to integrate all the different areas of struggle – social, economic, political, cultural – to achieve this ideal. His conception of a happy world was one that was gender-just, gender-equal and ultimately gender-free, among other things.

It is true that Lohia’s contribution to the women’s question was only in the realm of ideas – at best, specific demands for women’s empowerment made in party resolutions – and not really in concrete action. However, in a society that routinely violates women and where misogyny in thought, word and deed is the norm, his ideas on gender equality, stated with complete conviction, commitment and clarity, is deeply significant and very touching.

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of the Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) community’s literature, culture, society and culture. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +919968527911, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in

About The Author

Lalitha Dhara

Lalitha Dhara is a retired academic. She was the head of department, Statistics, and vice-principal, Dr Ambedkar College of Commerce and Economics, Mumbai. She has researched and authored a number of books, including Phules and Women’s Question, Bharat Ratna Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar and Women’s Question, Chhatrapati Shahu and Women’s Question, Periyar and Women’s Question, Lohia and Women’s Question, Kavya Phule (English translation of Savitribai’s first collection of poems).Previous

Do you know the feminist Lohia?

He dreamt of a coalition of the backward castes, Adivasis, minorities, working class and women which would unitedly oppose all the different axes of power – caste, class, race, gender – and usher in a new world

Lalitha Dhara March 21, 2017

Share onFacebookShare onLike on FacebookShare onX (Twitter)Share onWhatsAppShare onTelegram

23 MARCH: LOHIA JAYANTI

Dr Ram Manohar Lohia (23 March 1910 – 12 October 1967) occupies prime place among the ignited and charged minds of 20th-century India. He was a non-conformist, rational and sensitive human being. Equally, he was a profound, innovative and brilliant thinker. He dreamt of a society based on democracy, socialism, justice and peace. He visualized a world without borders and barriers. He was, simultaneously, a fierce nationalist and a global citizen, without contradiction.

Lohia’s father, Heera Lal, who was an ardent follower of Mahatma Gandhi, introduced the freedom struggle to him when he was barely in his teens. This left a deep mark on young Lohia. After his return in the early 1930s from Germany, where he obtained his doctorate, he plunged into politics. He started his political career with the Congress but started charting his own path through the 1940s and the 1950s, experimenting with different political formations, collecting fans and followers, along the way. By the mid-1950s, he had given shape and structure to his concept of an ideal society and the path towards it.