Pessimism of the Intellect, Optimism of the Will

“I’m a pessimist because of intelligence, but an optimist because of will.”

Antonio Gramsci in a Letter from Prison (December 1929)

Antonio Gramsci

“You must realize that I am far from feeling beaten…it seems to me that… a man out to be deeply convinced that the source of his own moral force is in himself — his very energy and will, the iron coherence of ends and means — that he never falls into those vulgar, banal moods, pessimism and optimism. My own state of mind synthesises these two feelings and transcends them: my mind is pessimistic, but my will is optimistic. Whatever the situation, I imagine the worst that could happen in order to summon up all my reserves and will power to overcome every obstacle.”

Patrick Lawrence in “Pessimism of the Mind, Optimism of the Will”

“It is Antonio Gramsci who is commonly credited with the thought, “Pessimism of the mind, optimism of the will.”

But it seems Romain Rolland, the French writer who won the Nobel Prize in literature in 1915, actually said it first.

Gramsci went on to make it a sort of political ethos, a guide to thought, or a way to manage one’s mind and live in the world as it is. We should take note of Gramsci’s views on optimism and pessimism.

He had much to say about both. Mussolini imprisoned Gramsci, a founding member of the Partito Comunista d’Italia, the PCI, in 1926, and he remained there until he died in 1937. It was in those years he wrote his celebrated Prison Notebooks—30 of them comprising 3,000 pages of reflections. Prison was a radical deprivation—he lost a public life of political participation to one of solitude and incapacitation. It was also 11 years of agony, fraught with insomnia, violent migraines, convulsions, systemic failure.

But Gramsci seems to have understood from the first that his most dangerous enemy was despair—lapsing into a state of purposeless quiescence, as if falling into a deep, dark hole.

Here he is in a letter to his sister-in-law, Tatiana, shortly after his arrest:

I am obsessed by the idea that I ought to do something für ewig [enduring, lasting forever]. . . I want, following a fixed plan, to devote myself intensively and systematically to some subject that will absorb me and give a focus to my inner life.

This is an early hint, in my read, of the thinking that was to come. In this letter Gramsci made deep connections—on one hand between pessimism and a state of depression and passivity, and on the other optimism and the taking of action. In the latter he saw salvation, and I could not agree more: I have long thought that a principal source of depression is the sensation of powerlessness. Whenever I have been overcome in this way I have said to myself, “Take the next step. It may be a mile, it may be six inches. Take it and you will have begun to act.”

Most of all, Gramsci seems to have concluded as his teeth fell out and he could no longer eat solids, that optimism is something one must purposefully marshal, cultivate, against all threats of dejection and hopelessness.

In letters and in passages in the Notebooks he identified optimism as essential to all political action.

What good would optimism be, he asked in “Against Pessimism,” published in 1924, when he was still able to place pieces in newspapers, “if we were… actively optimistic only when the cows were plump, when the situation was favorable?”

INTRODUCTION

Pessimism of the Intellect, Optimism of the Will

அறிவுஜிவியின்அவநம்பிக்கையும்

நம்பிக்கையின்உறுதிப்பாடும்

இந்த கூற்று என்ணோடு பலஆண்டுகள் பயணித்து வந்தது. . சமீபத்தில் ஓர் உரையாடலில் அதன்முழுமையான அர்த்தத்தையும்விளக்கத்தையும் புரிந்தும்உணர்ந்தும் கொண்டேன்.

அதாவது இது இருபத்தியோராண்டு கால் நூற்றாண்டு கடந்து வருகிறோம் இன்று 19- 20 ஆம் நாற்றாண்டு போல தொண்டு மட்டும்செய்ய இயலாது. இன்று வாழ்வதற்குஒவ்வோரு மணித்துளிகளும்வாழ்க்ககையை ஓட்டுவதற்கும் அதோடுஇணைந்த பிரச்சனைகளுக்கு முகம்கொடுத்தாக வேண்டிய கட்டாயத்தில்உள்ளோம் நாம் அனைவரும்.

இப்பொழுது புரிந்தது optimism என்னை நகர்த்தி இருக்கிறது அதற்குசூழ்நிலைகளும் அதற்குஉதவி இருக்கிறது.

இன்று pessimism கை ஓங்கிஇருக்கிறது என்று கூறி யாரும்தப்பிக்க முடியாது.

ஆனால்இன்றைய வாழ்சூழ்நிலைகளை கணக்கில் கொண்டுஎந்த திட்டத்தையும் நாம் யோசிக்கவேண்டும் என்பதே.

Debates,Conversations, Dialogues போன்ற சொற்கள் இன்று மிகப்பெரிய மாற்றங்கள் கண்டுள்ளன.LPG உலகமயமாக்கம், தாராளவாதம், தனியார்மயமாக்கல் விளைவாக 80-90 களுக்கு பிறகு மிகப் பெரியசவால்களை தோற்றுவித்திருக்கிறதுநம்மை அறியாமல் அவற்றுக்கு பலியாகிவருகிறோம்.

உரையாடப்படும் பொருள் பற்றியதகவல்கள கூட இல்லாமல் பலர் இன்றுதிக்கு தெரியாமல் தடுமாறிவருகின்றனர் .

உ..ம. NATO – நேட்டோ , என்பதைஎடுத்து கொள்வோம்,அது,எப்பொழுது,எதற்காக,பின்னணி,நோக்கங்கள், பற்றி நமது கல்வி பரம்பரைகற்று கொடுப்பதும் இல்லை அதன்உள் மர்மங்கள் தோலிறுத்துகாட்டப்படவும் இல்லை. அமெரிக்கா, இங்கிலாந்து,ஜெர்மணி, பிராண்சு, இட்டலி, ஸ்பெயின், போர்ச்சுகல்போன்ற காலனிய ஏகாதிபத்தியவல்லரசு நாடுகளின் பம்மாத்து கபடவேடங்களை பிரச்சாரங்களைஅறிக்கைகளில் கடுமையாக விமர்சித்துவிட்ட பெருமையில் முற்போக்குஇயக்கங்கள் திருப்த்தி அடைந்துவிட்டு கிடக்கின்றனர். அணு ஆயுதவியாபாரிகளின் பாசிசநடவடிக்கைகளை MILITARY- INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX இன் லாபப்வேட்டைகளை கட்டுடைத்தவிளக்கங்கள் இன்றி அவர்கள் ஏதோஜனநாயகத்தை காப்பதற்காகபாடுபடுவதாக காட்டிக் கொண்டு பவன்வருவதை நாம பாரக்கிறோம்.இது பற்றிநம் மொழியில் எழுத்துக்கள் மிக அரிதுஅல்லது இல்லை என்றே கூறலாம்.

இந்த பற்றாக் குறையை அவசரஅவசியமாக களையப்பட வேண்டும். ஆங்கிலத்தில் நாம்வாசிக்கும் பலகருத்துக்கள் உடனுக்குடன் தமிழில்கொண்டு வரப்பட வேண்டும்.

இயக்கத் தலைமை தங்கள் பண்புகளை புதிய போரிடம் ஓர் அமைப்பை கட்டும் போர்முனைகளின் ஓர் அங்கமாக கருதாமல் மேனேஜர் நிலைக்கு தங்களை தாழ்த்தி கொள்கிற போக்கு இன்று வலுப்பெற்று ஓங்கி வளர்ந்து வருகிறது

ஆங்கிலத்தில் தான் சிந்தனைகள் வளர்கின்றன என்று நாம் கூற முடியாவிட்டாலும் ஒரு அறிவியல் துறை வல்லுநரிடம் உரையாடிய போது அவர் கூறியது எனது நிலைப்பாட்டை உறுதி செய்கிறது. அதாவது ஜெர்மன்,பிரெஞ்ச், அல்லது வேறு ஆங்கிலம் அல்லாத ஐரோப்பிய மொழிகளில் ஆப்பிரக்க மொழிகளில் எந்த புதிய அல்லது அறிவியல் கட்டுரை வெளிடப்பட்டாலும் அது ஆங்கிலம் வழியாகதான் உலகிற்கு கிடைக்கிறது.

எனக்கு ஓரு நினைவிற்கு வருகிறது இதே போன்று அல்லது இதை ஒட்டிய தோற்றம் கொண்ட விவாதங்கள் வந்தன. அதாவது சிலர் ஆங்கிலத்திலேயே உரையாடுவதாகவும் ஆங்கிலம் அறியாத பலர் சிரம்மப்படுவதாகவும் குற்றச்சாட்டபட்டனர். அப்பொழுது கூட ஒருவர் கூறியது “ நீ புரட்சி செய்ய விரும்பினால் ஆங்கிலத்தை கற்றே தீர வேண்டும்”.

இந்த விவாதம் நம்மை ஆற்றல் படுத்த நிச்சயம் ஒரு மொழி தேவை நாங்கள் வாசிக்கக்காமலே டீ கடையில் உட்கார்ந்து கொண்டு அரசியல் பேசி விட்டு கலைந்து விடுவது போன்றது அல்ல மார்க்சியம் இன்று ஆழமாக பல கோணங்களில் விவாதங்கள் எல்லா மொழில் நடைப்பெற்றாலும் அது நமக்கு ஆங்கிலம் வழியாக மட்டுமே நம்மை வந்து அடைகிறது யாரும் மறுக்க மாட்டார்கள்

ஏற்கனவே நாம் கற்றதை மறுத்து புதியகற்றலை தொடங்கி ஆக வேண்டும்.

மார்ர்க்சியம் 19,20,21 ஆம்நூற்றாண்டுகளில பல்வேறுவகைகளில் வளர்ந்து வந்துள்ளன. சமூகம,தேசம்,பண்பாடு , அரசியல், வரலாறு அறிவியல் போன்ற பலதுறைகளில் புதிய வெளிச்சங்கள்விளக்கங்கள் கொடுத்த வன்னம்வளர்ந்து வருகிறது.

லெனின்,மாஓ,ஹோ- சி மின், ஃபிடல்காஸ்ட்ரோ இன்னும் பல ஆப்பிரிக்க ,லத்தின்அமெரிக்க மாரக்சிய தலைவர்களால்அறிவுஜீவிகளால் வளர்ந்த வன்னம்இருக்கிறது.

60களின் இறுதி பகுதியும் 70கள் முழுவதும் கொந்தளிப்பான மக்கள் எழுச்சி நிறைந்த நம்பிக்கை தரும் காலமாகவும் மாற்றங்களுக்கு பழுத்த ஒரு. காலப் பகுதியாக கருதவும் தீவிர activism தவிர்கக இயலாத்துமாகவும் இருந்தது.

இலங்கை மார்க்சிய அறிஞர் தோழர் ந. இரவீந்திரன் எனது கூட்டிற்கு வலுசேர்ப்பதை கவணிக்கவும்: அதே நேரத்தில் ஆங்கிலம் ஓர் காலனி ஆதிக்கத்தின் வேர் அதன மீது கொள்ளும் ஆர்வம் , தேவை ஆகியவற்றை ஆங்கில மோகம் என்று புறம் தள்ளி விடுவதும் மிகுந்த ஆபத்தானது.

“20 ஆம் நூற்றாண்டு (80 ஆம் ஆண்டுகள் வரை) சமூக மாற்ற சக்திகளுக்கு நம்பிக்கைகளைஊட்டுவதாக அமைந்திருந்தது. அதன் உச்சமாகஅமைந்த ருஷ்யாவில் இருந்து ஜெர்மன், இத்தாலிஆதியன சிறு (அடிப்படையான) வேறுபாட்டைகொண்டிருந்தது. ஏகாதிபத்திய மறுபங்கீட்டுஉந்தல் காரணமாக அவ்விரு நாடுகளும் பாசிசநடைமுறையைக் கையேற்க வேண்டி இருந்தது. பாசிசத்தின் களமாக தமது மண் மாறியதன்பேறான அறிதல் புலத்துக்கான அவநம்பிக்கைப்பக்கங்களையும் மேவி எதிர்கால உலகம் ‘பாட்டாளிவர்க்கத்தால் வெற்றி கொள்ளப்பட்டுசோசலிசத்தை நாடுவதனை எதனாலும் தடுக்கஇயலாது’ என்ற நம்பிக்கை அங்குள்ள மார்க்சியசிந்தனையாளர்களுக்கு இருந்தது.

இன்றைய இந்தியா அன்றைய ஜெர்மன், இத்தாலிஎதிர்நோக்கிய சமூக-பொருளாதார-பண்பாட்டியல்நெருக்கடிக் கட்டத்துக்கு ஒப்புவமைகொள்ளத்தக்க இடத்தில் உள்ளது.

அன்றிருந்தது போல ‘பாட்டாளி வர்க்கப் புரட்சிமுழு உலகை மாற்றும்’ என்ற நம்பிக்கை ஒளிஇப்போது இல்லை; அதேவேளை ஏகாதிபத்தியஅணி அன்றைய நிலையைக் காட்டிலும் மிகமோசமான வீழ்ச்சியை முகங்கள்வதைகாணக்கூடியதாக உள்ளது.

இந்த மாற்றத்தை மக்கள் விடுதலைக்கானதாகமாற்றும் வகையில் மார்கசியத்தை எவ்வாறுவளர்த்தெடுத்துப் பிரயோகிக்க இயலும் என்பதுபற்றிய தேடல்கள் உலகளவில் பலமார்க்சியர்களால் முன்னெடுக்கப்படுகின்றன. அவற்றைத் தமிழில் கொண்டுவரும் தேவைஉள்ளதல்லவா?”

லெனின் கூறுவதை பார்ப்போம்

“ நமது அரசப் பொறியமைவைப்புத்தமைக்கும் பொருட்டு எப்பாடுபட்டேனும்நாம் மேற் கொண்டாக வேண்டிய பணிஎன்னவெனில் முதலாவதாக்க் கற்றல்கற்றறிதல், இரண்டாவதாக கற்றறிதல், மூன்றாவதாக கற்றறிதல் கற்ற பின்னர் அந்தவிஞ்ஞான அறிவுப பயனிலாப் பண்டமாகவோஆடம்பரமான வாய்பேச்சாகவோ அமைந்துவிடாதபடி ( அடிக்கடி நம்மத்தியில் இப்படிநேர்ந்து விடுவதை மறைக்காமல்ஒப்புக்கொண்டுதான் ஆக வேண்டும் ) விஞ்ஞான அறிவு மெய்யாகவே நமது ஊனும்குருதியுமாகி விடுமாறு முழுமையாகவும்மெய்யாகவும் நமது அன்றாட வாழ்க்கையின்உள்ளடக்கக கூறாகி விடுமாறு உறுதி செய்துகொள்ளுதல் வேண்டும் எனப் குறிப்பிடுகிறார்”

3 மில்லியன் வங்காளிகள் படுகொலை பற்றிபல புதிய தகவல்கள் வந்துள்ளன.

Churchill’s policies to blame for millions of Indian famine deaths, study says

By Bard Wilkinson, CNN

3 minute read

Published 3:16 PM EDT, Fri March 29, 2019

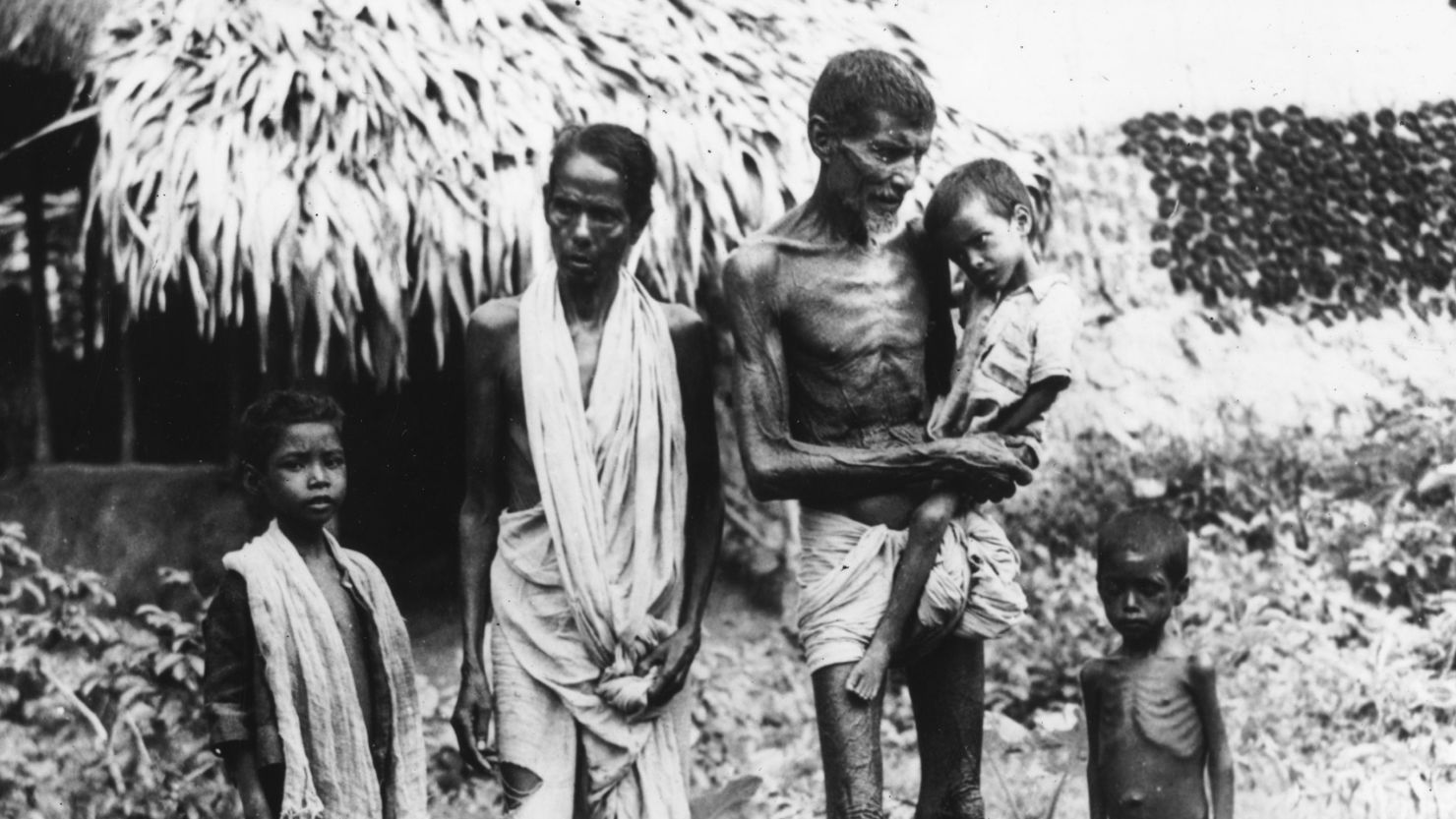

This Indian family arrived in Kolkata in 1943 in search of food. Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesCNN —

Winston Churchill’s policies caused a famine that claimed more than 3 million Indian lives, according to a new study using soil analysis for the first time to prove the origins of the disaster.

The 1943 Bengal famine was the only famine in modern Indian history not to occur as a result of serious drought, states the report, which was conducted by researchers in India and the United States.

“This was a unique famine, caused by policy failure instead of any drought,” Vimal Mishra, the lead researcher and an associate professor at the Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar, told CNN.

Ad Feedback

Researchers used weather data to gauge the amount of moisture in the soil during six major famines in the subcontinent between 1870 and 1943.

“There have been no major famines since independence,” said Mishra. “And so we started our research thinking the famines would have been caused by drought due to factors such as lack of irrigation.”

RELATED ARTICLEThe real-life story of ‘The Favourite’ fascinated Winston Churchill, too

They found that five of the famines were largely caused by droughts, but in 1943, at the height of the Bengal famine, rain levels were above average, according to the study published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

“The Bengal famine of 1943 was completely because of policy failure,” Mishra said.

Policy lapses such as prioritizing distribution of vital supplies to the military, stopping rice imports and not declaring that it was actually a famine were among the factors that led to the magnitude of the tragedy, he added.

Mishra said examining previous famines showed that policy could be effective. “In the 1873-74 famine, about 25 million people were affected, but mortality was almost negligible.”

According to Mishra, the low mortality was due to food imports from Burma – now known as Myanmar – and relief aid provided by the British government. Richard Temple, who was the Bengal lieutenant governor, imported and distributed food and relief money and thus saved a lot of lives, he said.

But he said the British government criticized Temple’s use of resources for saving Indian lives and during the next drought in the 19th century, his policies were dropped and millions more people died.

The Nobel prize-winning economist Amartya Sen argued in 1981 that there should have been enough supplies to feed Bengal in 1943.

In a recent book, writer Madhusree Mukerjee argued the famine was exacerbated by Churchill’s decisions.

She wrote that famine was caused in part by large-scale exports of food from India. India exported more than 70,000 tons of rice between January and July 1943 as the famine set in, she said.

Not everyone lays the blame at the Prime Minister’s door, however. Churchill biographer Andrew Roberts wrote in an opinion column on Britain’s i news website last year that Churchill “did all he could to relieve the terrible Bengal Famine subject to the exigencies of the Japanese holding Burma and their submarines infesting the Bay of Bengal.”

ஜாலியனவாலாபாக் படுகொலை பற்றியும்எப்படி மக்கள் அங்கு கூடுவதற்கு ஜெனரல்டையர் செய்த சதிகள் பற்றி சற்று முன் வந்ததகவல்கள் நெஞ்சு பொருக்குவில்லை .

மேலும் பகத்சிங் , ராஜகுரு, சுக்தேவ்தூக்கிலிடப்பட்ட பின் நடந்துள்ள கோரகொடுமைகள் உலக மக்களின் மனசாட்சியை தட்டி எழுப்பும் ஆனால்இப்பொழுதும் கூட தகவல்களாக கடந்துசெல்லும் போக்கை என்னவென்று கூறுவது. வெட்கப்பட்டடு சும்மா இருக்க முடியாது.

Jallianwala Bagh massacre: How Colonel Dyer exploited the planned gathering as a ‘gift of fortune’

In a new book, Kishwar Desai writes about how the residents of Amritsar were manipulated and insufficiently warned before the massacre in 1919.

Nov 12, 2018 · 08:30 am

Since April 13 was a Sunday, many of the shops were closed in any case and the hartal was still on. With the constant presence of the army on the streets, few people would have been out in the morning. However, at 9.30 am, Dyer decided to make two proclamations – neither of which was likely to have been heard. The Naib Tehsildar who was making the proclamations said he had halted at around 19 places where anywhere between 100 to 500 people had gathered. Most of them, he said, were jeering, and it was doubtful if anyone grasped the importance of his words. He also mentioned that there were announcements of the Jallianwala Bagh meeting taking place simultaneously, or at least discussions about it.

There are also reports of people staying indoors when Dyer’s entourage passed by. In any case, the terms of the proclamations were unclear, perhaps deliberately so. They were read out to the beat of a drum by the Naib Tehsildar.

The first proclamation said:

The inhabitants of Amritsar are hereby warned that if any property is destroyed or other outrages committed in the vicinity of Amritsar it will be taken that incitement to perform these acts originates from Amritsar City, and such measures will be taken by me to punish the inhabitants of Amritsar according to Military law.

All meetings and gatherings are hereby prohibited and I mean to take action in accordance with Military Laws to forthwith disperse all such assemblies.

It was signed “RE Dyer, Brigadier General, Commanding Jullundur Brigade”.

This was a printed proclamation, as was the first part of the second one. But the final and most crucial part of the second proclamation, which spoke of dispersal by “force of arms”, was only read out.

The first part said:

It is hereby proclaimed to all whom it may concern, that no person residing in the city is permitted or allowed to leave the city in his own private or hired conveyance, or on foot without a pass from one of the following officers:

The Deputy Commissioner

The Superintendent of Police – Mr Rehill

The Deputy Superintendent of Police – Mr Plomer

The Assistant Commissioner – Mr Beckett

Mr Connor, Magistrate

Mr Seymour, Magistrate

Ara Muhammad Hussain, Magistrate

The Police Officer-in-charge of the City Kotwali

This will be a special form and pass

The next part of the proclamation, which was only read out, said:

No person residing in the Amritsar city is permitted to leave his house after 8.00 pm.

Any persons found in the streets after 8.00 pm are liable to be shot.No procession of any kind is permitted to parade the streets in the city, or any part of the city, or outside of it, at any time. Any such processions or any gathering of four men would be looked upon and treated as an unlawful assembly and dispersed by force of arms, if necessary.

A note by Irving clarified, “I have put in the words ‘if necessary’ in the draft which I was asked to edit in legal language so as to bring it into line with ‘liable to be shot’ in paragraph 2.”

But did the addition of these words really have any preventive impact or was it only to protect Dyer and Irving?

This second (ambiguous) statement was read out in Urdu and Punjabi and it is the addition of the last two words that indicated that some kind of warning would be given before shooting. The additional information that people would be shot if they were out after 8.00 pm, also made it confusing for most. Many who heard it may have thought that people would only be shot after 8.00 pm if they were still on the streets. In any case, the proclamation was made at 19 places, none of which were close to Jallianwala Bagh or even the Golden Temple – the most crowded part of the city and an area where even visitors were likely to throng to.

For the residents of Amritsar who wanted to attend, the fact that a respected local elder and barrister, Kanhya Lal, was going to address the assembly meant they could expect to receive some “sound advice”.

Kanhya Lal himself said in his evidence to the Congress Committee: “I heard that some men (who have not been traced up to this time to my knowledge) had on the 13th April, proclaimed that a lecture would be given at Jallianwala Bagh by me. This led or induced the public to think that I should have given them some sound advice on the situation then existing.”

A boy with a tin can had also gone around announcing that Kanhya Lal would preside over the 4.30 pm meeting at Jallianwala Bagh. He too could not be traced later. Neither could Hans Raj, the person said to have called the meeting, be questioned about the meeting, as he became a government witness in the “Amritsar Conspiracy Case”. He did not give evidence before the Hunter Committee as he had left for Mesopotamia by then.

Some historians suspect that Hans Raj was used to gather a crowd because Dyer wanted a large number of people to be “punished”.

That the meeting was going to be held at 4.30 pm was confirmed at 1.00 pm to Dyer, who remained at Ram Bagh till at least 4.00 pm, and later said, “I went there as soon as I could. I had to think the matter out. I had to organise my forces and make up my mind as to where I might put my pickets. I thought I had done enough to make the crowd not meet. If they were going to meet I had to consider the military situation and make up my mind what to do, which took me a certain amount of time.”

The “military situation” meant he must have asked for a map of the area and studied how he could attack the enemy – with maximum impact. He was proud of his technical skills.

Something of what was going through his mind is in his biography, The Life of General Dyer, written by Ian Colvin, in close association with Dyer’s wife, Anne, in 1929. Puzzled about how to attack the “rebels”, he had exulted over the “gift of fortune” when the “rebels” decided to congregate in an open space. He wanted to take “immediate action” on the Amritsar “mob” which had tasted blood and “began to feel themselves masters of the situation”. He realised that he needed to bring a sizeable crowd together, but how could he do it?

In the narrow streets, among the high houses and mazy lanes and courtyards of the city the rebels had the advantage of position. They could harass him and avoid his blow. Street fighting he knew to be a bloody, perilous, inconclusive business, in which, besides, the innocent were likely to suffer more than the guilty. Moreover, if the rebels chose their ground cunningly, and made their stand in the neighbourhood of the Golden Temple, there was the added risk of kindling the fanaticism of the Sikhs. Thus he was in this desperate situation: he could not wait and he could not fight.

The fact that the rebels themselves chose to go to an open space, where they could be corralled in was an unexpected “gift of fortune”: something he could only have hoped for and not devised. As his admirer Ian Colvin said, now the enemy was within easy reach of his sword. “The enemy had committed such another mistake as prompted Cromwell to exclaim at Dunbar: ‘The Lord hath delivered them into my hands.’”

For Dyer, this was not a murderous attack on defenceless, innocent people. For him the people assembled were all guilty; it was a state of war, in which he wanted to teach them a “moral” lesson. He assumed all of those present at Jallianwala Bagh to be guilty without any idea of who they were.

Dyer’s planning was impeccable. He ensured that he conscripted soldiers who were sufficiently removed from Punjab so they were able to shoot without compunction. He deliberately took no British troops, because he wanted no blame to fall on them. He took none of the other commanders – what would have happened if they resisted his orders?

He was thus accompanied by twenty-five Gurkhas and twenty-five Baluchis armed with rifles. These were fierce fighters and the Gurkhas, especially, were incredibly loyal. They had no connections with Punjab, they did not even know the language. Aware that if the crowd rushed towards him, there might be hand-to-hand combat, he took forty Gurkhas armed only with khukris. He was prepared for a bloodbath. Knowing fully well that they would not fit into the entrance, he took two armoured cars. This was more for effect and, if things got out of hand, for escape. He also placed pickets all along the routes to the Bagh so people could be shot even if they escaped.

As the Hunter Committee admitted in its report to the British Parliament in 1920, “It appears that General Dyer, as soon as he heard about the contemplated meeting, made up his mind to go there with troops and fire” because they had “defied his authority” by assembling. The fact that they may have been unaware of his prohibitory orders was not important for him. He wanted to create a “wide impression”.

He said, “If they disobeyed my orders it showed that there was complete defiance of law, that there was something much more serious behind it than I imagined, that therefore these were rebels, and I must not treat them with gloves on. They had come to fight if they defied me, and I was going to teach them a lesson.”

In his defence, British historians have said that he took a very small force and that he was surprised by the crowd that he found, forcing him to react the way he did. This is contrary to the facts. He had carefully calculated how he would spread the force available to him all around the city and an aircraft flying over the meeting had already conveyed to him the strength of the crowd.

He stationed around fifty men to protect his Ram Bagh base, and also dropped off five pickets of forty each en route to Jallianwala Bagh. It was thus that he was left with “fifty rifles, forty armed Gurkhas and two armoured cars”. But he also had another fifty stationed at the Kotwali, which was not very far from Jallianwala Bagh.

Of course, the people assembling at the Bagh had no inkling of his plan, while he knew about their meeting. The CID, based in the Kotwali, were keeping a close eye on the assembly, as they had been asked to do. They too did not request people to leave, or stop them from going to the Bagh, following the morning proclamation by Dyer. This would have added to the confidence of the gathering at Jallianwala Bagh, as the police would have watched them assemble and done nothing about it. Some members of the CID and a few police constables were even seen at the gathering – as was normal.

It is also interesting to note that despite the large presence of the army and the discomfort and deprivations they had been subjected to, the people of Amritsar still had faith in the system, in each other and, to a large extent, the British. They were defiant, but also sombre – after the deaths on April 10, they could not imagine that a peaceful gathering, so close to the Golden Temple, on the festive day of Baisakhi could become a bloodbath. The events of April 10 were seen as an aberration. The two days of calm that followed had given them false hope, leading them to believe that things had calmed down and they could carry on with their saty

மேலும் பகத்சிங் , ராஜகுரு, சுக்தேவ்தூக்கிலிடப்பட்ட பின் நடந்துள்ள கோரகொடுமைகள் உலக மக்களின் மனசாட்சியை தட்டி எழுப்பும் ஆனால்இப்பொழுதும் கூட தகவல்களாக கடந்துசெல்லும் போக்கை என்னவென்று கூறுவது. வெட்கப்பட்டடு சும்மா இருக்க முடியாது.

case that led to Bhagat Singh’s execution

Pakistan’s Supreme Court ruled that former PM ZA Bhutto was hanged without a fair trail. Now, can the Lahore Conspiracy Case be revisited?

Apr 06, 2024 · 03:30 pm

On March 6, the Supreme Court of Pakistan ruled that ousted prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto had been unjustly hanged in 1979. The court’s ruling was following a presidential reference filed 12 years ago.

It was a reminder of the execution of freedom fighter Bhagat Singh and his comrades nearly a century ago in 1931.

In 2013, my friends in Lahore, advocate Abdul Rasheed Qureshi and his son Imtiaz, both senior lawyers of the Lahore High Court, petitioned the court to reopen the Lahore Conspiracy case that led to the execution of Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev Thapar and Shivaram Rajguru.

Qureshi and Imtiaz had founded the Bhagat Singh Memorial Foundation in 2010 to take forward the memory of the revolutionary and freedom fighter born on Pakistani soil in Banga.

Qureshi passed away in 2021.

Imtiaz told Sapan News that the Lahore Conspiracy case did not fulfill the requirements of justice as due process had not been followed.

Bhagat Singh’s name was not even mentioned in the police report that was used as the basis of the case. It was also not brought before a trial court – which is also what happened with Bhutto.

The three-judge tribunal hearing the Lahore Conspiracy case pronounced the death sentence without hearing the testimonies of as many as 450 witnesses, or giving the defendants a chance to appeal. The entire judicial procedure was so defective that veteran lawyer and scholar AG Noorani has called it a “judicial murder”.

The Lahore High Court dismissed Imtiaz’s case last year but the Supreme Court’s ruling on the Bhutto trial has encouraged the lawyer to file a similar petition. He plans to do this after Ramzan.

Shared legacy

Bhagat Singh’s political influence began early as a follower of Mohandas Gandhi’s non-violent struggle for independence from the British. But years of witnessing the injustices of colonial rule left Singh disillusioned, pushing him to join forces with other revolutionary figures.

Since Partition in 1947, Pakistan and India have aggressively promoted separate identities based on religion. But on both sides, there exists an understanding of fluid identities. On either side, people claim Bhagat Singh and his comrades as their own, a shared historical legacy that endures.

In 2007, Irtiqa, a progressive Urdu journal from Karachi, marked Bhagat Singh’s centenary birthday by publishing a special issue with poems and other materials about him.

The volume included an essay by Zaheda Hina, an Urdu writer based in Karachi, who described Bhagat Singh as a “son of Pakistan”. Singh was born in Lyallpur district, now Faisalabad on September 28, 1907, and executed in Lahore on March 23, 1931, both in what became Pakistan. Activists and civil society groups gather at the spot every year on March 23 to pay tribute.

Following consistent campaigning by Singh’s supporters, the Lahore municipal corporation in 2012 agreed to re-name Shadman Chowk, where the execution point of Central Jail once stood, as Bhagat Singh Chowk. Artist Salima Hashmi, daughter of poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz, was part of the expert committee that made the recommendation.

But a group of traders and clerics obtained a stay order from the Lahore High Court, so the decision was never implemented. Rasheed has filed a counter petition for contempt of court, urging that the order be implemented.

In the face of threats and attacks from extremist groups since 2013, the supporters of Bhagat Singh supporters appeal every year to the Lahore administration for security.

‘Inqilab zindabad’

Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev were executed on the evening of March 23, 1931 at 7 pm. Executions normally take place in the morning and the three freedom fighters were scheduled to be executed the following morning.

But fearing a massive protest, the colonial administration advanced the execution by 12 hours.

As a protest on the evening of March 22 ended, the demonstrators heard about the executions and gathered at the gate of the Lahore jail.

A jail official told an Indian nationalist living nearby that the three had thrown off the black hoods, usually used to cover the faces of those being executed, declaring that they were not criminals. Holding their heads aloft and shouting slogans of “Inqilab Zindabad” (long live revolution), the three freedom fighters strode to the gallows.

Decades later, Iraq President Saddam Hussain similarly refused to wear a hood before he was executed in 2006 on the orders of an Iraqi Special Tribunal.

British officials mutilated the bodies of the three freedom fighters, stuffed them into jute sacks, burned them and threw them into the Sutlej River near Ganda Singh Wala village. Locals, along with Singh’s younger sister Bibi Amar Kaur, Lala Lajpat Rai’s daughter Parvati Bai, who had followed the officials from Lahore jail, retrieved the half-burnt body parts and brought them back to Lahore for cremation rituals.

More than 50,000 people attended the funeral. There was also a huge gathering at Lahore’s Minto Park the next day, according to a front-page report in The Tribune of Lahore on March 26.

The interest Bhagat Singh in Pakistan and elsewhere has only grown. In the days before the 1965 war, Indian visitors to Punjab in Pakistan would invariably visit Chak No 105, Bhagat Singh’s birthplace.

With visa issues, the stream of visitors has dried up – but the interest has only grown.

The Lyallpur Historian Club organises lectures on Bhagat Singh and celebrates his birth and death anniversaries every year at his place of birth.

The family allotted to Bhagat Singh’s birth home has created a two-room museum with pictures of freedom fighters of that period – Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims. During his tenure as India’s ambassador to Pakistan, TCA Raghvan had also visited the house.

A global icon

Writers, researchers and scholars across the divide have worked hard to uncover details of Bhagat Singh’s life and execution.

Poet Sheikh Ayaz has written an epic on Bhagat Singh in Sindhi while Punjabi poet Ahmad Saleem has published a poetry collection titled Kehdi Maan ne Bhagat Singh Jammiya (Which mother gave birth to Bhagat Singh).

Several books have been published and more are in the works. Ammara Ahmad, a journalist and scholar, is planning her research on the “Footsteps of Bhagat Singh in Lahore”. Historian Waqar Piroz, who retired from the Government College Lyallpur (Faisalabad), wrote an Urdu biography of Bhagat Singh, Sarfarosh Sardar Bhagat Singh (Fiction House, Lahore, 2023).

British Indian scholar and lawyer Satvinder Juss has published two books containing valuable information as he had obtained access to study the 134 files of the Bhagat Singh case at the Punjab Archives in Anarkali, Lahore.

In 2014, a Pakistani historian said that Pakistan was planning to digitise these files and make them available publicly. Ten years later, this has yet to happen. But in 2018, the Punjab Archives, Lahore, held an exhibition on the Bhagat Singh case, exhibiting many documents from these files for the first time.

Monthly Review ex-editor and director Michael D Yates and I co-edited The Political Writings of Bhagat Singh published by LeftWord India in December 2023, which will be published by Review Press, New York, this year.

Bhagat Singh’s enduring symbolism as a revolutionary international icon is reminiscent of Argentinian icon Che Guevara, connecting the revolutionary traditions of South Asia and South America.

Chaman Lal is a leading authority on Bhagat Singh, and recently retired as a professor from Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He can be contacted at Chamanlal.jnu@gmail.com.

This is a Sapan News syndicated feature.

இது போன்ற ஆயிரக்கனக்கான நிகழ்வுகள்வந்த வன்னம் உள்ளன. இவற்றில் நம் சார்பில்ஒரு சிறிய குறுக்கீடு செய்யும் முயறச்சியாகசில திட்டங்களை முன் வைக்கிறோம். உங்கள் ஒத்துழைப்பை நாடுகிறோம்

On Revolutionary Optimism of the Intellect

Published: Oct 11, 2016

Main Article Content

Leo Panitch

Abstract

It is impossible to read Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks without appreciating how far he actually transcended the dichotomy between pessimism of the intellect and optimism of the will. He did so precisely by applying his stunningly creative intelligence to what really would need to be involved in the creation of a new type of political party, which in homage to another great Italian political theorist who could also be described as a realist with imagination, he called the ‘modern prince’. In trying to articulate the form of a party capable of navigating a revolutionary transformation in conditions where the state was deeply rooted in society, Gramsci was doing the very opposite of entrusting it to revolutionary will to usher in the spontaneous transformative ‘event’ that is rather in fashion among some radical intellectuals today.

What many intellectuals today may find troubling about optimism of the intellect is the credit they fear it may lend to all that has emanated from the ‘age of reason’, with its universalist claims to truth and its evolutionist proclamations of progress. The abdication of so many left intellectuals from the vocation of telling the truth on these grounds was no doubt partly the result of political and intellectual shortcomings on the traditional left. But they have sometimes only generalized what was wrong with the narrow class struggle perspective that crudely labelled truth either bourgeois or proletarian, applying the same type of dichotomy to race and gender, and indeed to any and all asymmetric relations of power.

But optimism of the intellect does not involve embracing any teleological laws of historical progress. Optimism of the intellect in fact involves being sensitive to contingency in human history, with contradictions and crises not the only variable factors in determining the scope and possibilities of such contingency, but also the capacities of collective human agency as especially crucial variable factors in developing transformative institutional forms. To get to where Marx or Gramsci wanted us to get involves probing the limits of economic and political institutions. And to do this it is also important to pay close attention to such great pessimists of the intelligence as Max Weber on state bureaucracy and Roberto Michels on party oligarchy. This is precisely because we need to identify the actual institutional barriers that lie in the way of replacing the capitalist rationality of market competition with the socialist rationality of collective planning, so we can at least minimize those barriers through articulating the institutional forms that can develop popular capacities for genuinely democratic participation as well as complex representation and administration. The political purpose for this kind of institutionalism is exactly the opposite of validating path dependency, insisting rather on institutional contingency to the end of discovering how to transform institutions in socialist ways.

Article Details

Issue

Vol. 53: Socialist Register 2017: Rethinking Revolution

Pessimism of the Will

Viewpoint Magazine

Asad Haider May 28, 2020

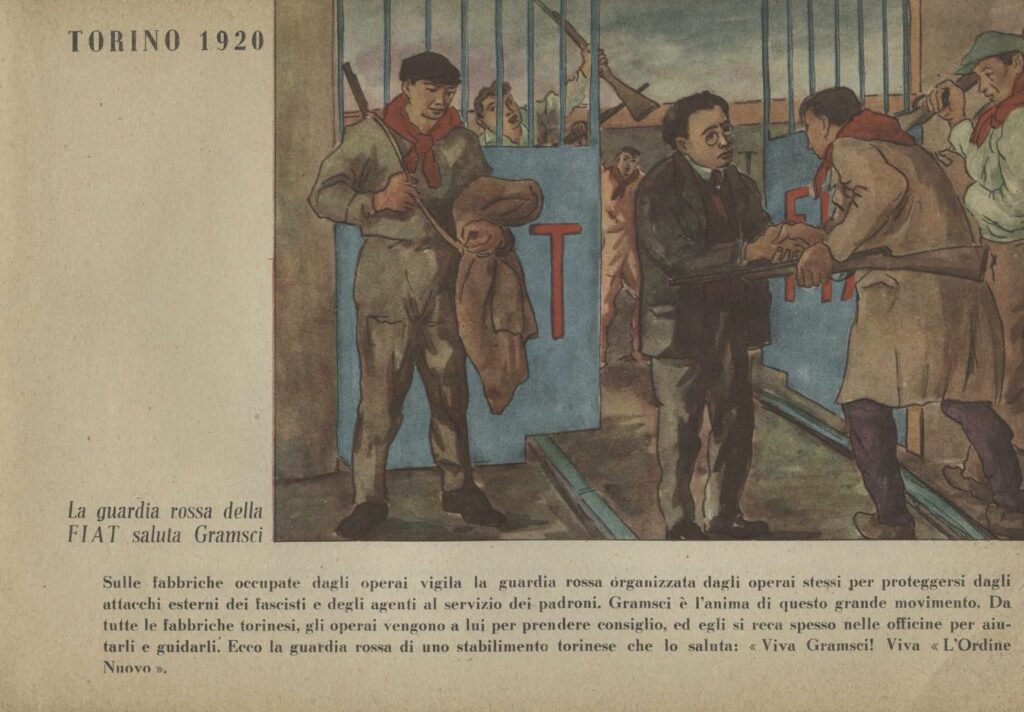

In April 1920, Italy was in crisis. The previous month at the Fiat auto factory in Turin, management had set back the clock hands of the factory for daylight saving’s time, without asking permission from the democratic workers’ councils that had been spreading throughout Italy’s factories. A chain of work stoppages had popped up in protest. But as tense negotiations continued, with a massive lockout by management, it became clear that what was really at stake was the existence of the factory councils themselves. 1 The whole city entered into a general strike in defense of the councils, which Antonio Gramsci would hail later that year in a report for the Comintern as “a great event, not only in the history of the Italian working class but also in the history of the European and world proletariat,” because “for the first time a proletariat was seen to take up the fight for the control of production without being forced into this struggle by unemployment and hunger.” 2

This was a peak moment in Italy’s biennio rosso, the “two red years” of 1919-1920, which saw not only mass strikes but also occupations of factories by the workers’ councils, which experimented with self-management of production. Rising during the red years, L’Ordine Nuovo (The New Order), both a newspaper and a political tendency which Gramsci helped found in Turin within the Italian Socialist Party, reflected on the greater meaning of these struggles. In the pages of L’Ordine Nuovo Gramsci introduced a phrase he would repeat throughout his life: “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.” 3

The L’Ordine Nuovo tendency based itself on the model of the Russian Revolution, and saw the factory councils — which Gramsci understood to be the equivalent of the Russian “soviets” — as the foundation of the coming revolution, and the workers’ state which that revolution would establish. After the bureaucracies of the Socialist Party and its affiliated union, the General Confederation of Labor, obstructed the further development of the general strike in a revolutionary direction, a contradiction which would resurge around the factory occupations in the fall, Gramsci’s tendency, along with other elements on the left of the party, split off to found the Communist Party of Italy in 1921. In reaction to the upheaval of these struggles and their emancipatory possibility, fascist violence intensified, leading to the ascendancy of Benito Mussolini. The fascist regime outlawed the Communist Party, and in 1926 Gramsci was imprisoned. He would die in prison in 1937.

“Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will” has become one of the classic clichés of politics. It is supposed to suggest that one should have clear-eyed recognition of how bad things are, without losing hope; it means the conscious volition for changing the world nevertheless.

Nevertheless, it might be wise to be somewhat suspicious of a slogan which seems so reassuring, applicable to every context without modification. That it is attributed to Gramsci does not really help matters. Due perhaps to the difficulty and complexity of Gramsci’s writings, often attributed to the need to write esoterically under the watchful eye of the fascist prison censor, contemporary commentators have sometimes appropriated them in a vague and decontextualized manner. It is common to see Gramsci invoked to advocate gradualist programs of reform, with the language of “war of position,” or to see him turned into a cultural critic who advocated building “counter-hegemony” in the academy — his ardent enthusiasm for the insurrection of the workers’ councils seems to drop out of the picture.

These days we need to cheer ourselves up, but without pretending that coronavirus and climate change aren’t real. As Fiat workers today go on strike over the safety risks of coronavirus, compelling management to shut down the plants in Italy and North America, what better authority than Gramsci, martyred by fascism and writing between two devastating world wars, to lend his approval to our desperate bid for optimism?

Removed from the very specific context in which he initially wrote these words, however, and the very different contexts in which he would later repeat them, this motto resembles nothing more than a poster on the wall of a middle-school classroom.

Party

The line is not originally Gramsci’s; he drew it from the French left-wing writer Romain Rolland (who would later campaign for Gramsci’s release from prison), in a 1920 review of Raymond Lefebvre’s novel The Sacrifice of Abraham. 4 Gramsci first used the phrase in his “Address to the Anarchists,” published in L’Ordine Nuovo in April 1920, just as the situation in Turin was accelerating towards the general strike.

It must be noted from the outset that anarchists had played an absolutely fundamental role in the organization of the strikes and councils, and had produced some of the movement’s most effective and dedicated militants. 5 In making his case for the superiority of Marxist theory, then, Gramsci had to bend the stick rather far. Anarchism, he argued, in its abstract opposition to the state, failed to grasp that true freedom for the workers would only come from the establishment of a workers’ state, the determinate form of human action which had been demonstrated and guaranteed by the Russian Revolution. He introduced the slogan “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will” specifically to sum up “the socialist conception of the revolutionary process.” 6 According to the anarchists, Marx’s “pessimism of the intellect” saw the conditions of workers as so miserable that the only possible change would come through an authoritarian dictatorship; but Gramsci replied that “socialist pessimism” had been confirmed by the horrors of the First World War and the extreme poverty and oppression that followed. The proletariat was geographically dispersed and disempowered by its deprivation, and formed unions and cooperatives out of sheer necessity, not as free political action. Its activity was totally determined by the capitalist mode of production and the capitalist state. It was thus was purely an illusion, he concluded, to expect these oppressed and subjugated masses to “express their own autonomous historical will.” 7

In other words, the pessimism of the intellect demonstrated not just that the situation was bad, but that the basis for revolutionary action did not already exist. It could only be brought about by “a highly organized and disciplined party that can act as a spur to revolutionary creativity.” 8 The optimism of the will, then, was not merely the belief that it was possible that things could get better, but the very specific and concrete form of action which was the vanguard party and its mission of establishing a workers’ state.

Gramsci, in other words, was operating squarely within the Leninist problematic. We are past the point today of the forced choice between caricaturing this problematic or dogmatically asserting its supremacy. Rather, we can try to situate it historically and understand its validity and limits. As Christine Buci-Glucksmann writes in her classic study, Gramsci and the State, emphasizing the character of Gramsci’s thought as a “continuation of Leninism, in different historical conditions and with different historical circumstances”: “to continue Lenin means a productive and creative relationship that can never be exhausted in the mere application of Leninism by studious pupils, but involves its translation and development. This nuance is of capital importance, underlining the fact that the only ‘orthodoxy’ permissible is that of the revolution.” 9

In 1902 with What Is to Be Done? V.I. Lenin repeated, for Russian conditions, the orthodoxy of the German Social Democratic Party. According to this orthodoxy, left to their own devices workers would only engage in the immediate, everyday struggles to better their conditions. The consciousness that this class struggle had to be taken further, to the level of the conquest of political power, would have to be introduced from the outside, by intellectuals. Politics would come not from spontaneous action by workers but the organization of a vanguard party of revolutionaries.

Lenin’s articulation of this thesis was divisive, to say the least. The orthodox theory saw this process as happening by virtue of historical laws, drawing more and more people into the industrial working class, gathering them into unions, and eventually allowing them to achieve a majority in parliament. Lenin’s writings from What Is to Be Done? to The State and Revolution in 1917 show him formulating a conception of politics which could not be reduced to historical laws. Lenin advanced the thesis that politics is not just always there, but develops under specific conditions. As Gramsci said in his early, “voluntarist” text “The Revolution Against ‘Capital,’” this constituted a refutation of the reigning mechanistic interpretation of Marxism, which, “contaminated by positivist and naturalist encrustations,” insisted that “events should follow a pre-determined course.” The Bolshevik revolution, Gramsci argued, demonstrated the necessity of “active agents” of politics, “to ensure that events should not stagnate, that the drive to the future should not come to a halt.” 10

The first Leninist condition of politics was the vanguard party, that group of dedicated militants which would erase the distinction between intellectuals and workers in a collective leadership. The party would be capable of recognizing the revolutionary potential of spontaneous movements, and could bring them the socialist consciousness which would realize this potential. But by 1917, Lenin came to see the party as existing alongside another site of politics: the soviet. Anticipating Gramsci’s account of the political role of knowledge, we can say that this new site of politics went beyond the restricted intelligence of the militants who composed the vanguard party to the mass intelligence of the radically democratic councils, the soviets. The orthodox theory had sought to enter the parliamentary state and use it as an instrument for the interests of the working class. In Lenin’s vision the soviets would actually take the place of the previously existing state, allowing ordinary people to participate in the administration of society. The soviet would be the form of genuine self-governance, a higher form of democracy than every previously existing form of a parliamentary democracy.

What happened instead is that the centralized authority of the party became the state, and subordinated the mass intelligence of the soviets to the principle that only the party thinks. Lenin, in the paradoxical position of state revolutionary, called for a society in which “every cook can govern” (to adopt C.LR. James’s optimistic rendering of Lenin’s phrase), but in practice it was the party-state which reigned.

For the remainder of the twentieth century emancipatory politics would have to refer to this exemplary instance in which bourgeois political power was overturned by the party becoming the state. Leninism was a moment in the history of emancipatory politics, but over the course of its history it found itself running up against the limits of the party-state; we are still in search of an emancipatory politics which goes beyond the party-state.

Today Gramsci’s motto is widely repeated, but it appears to have become completely detached from the underlying strategic and organizational questions that framed Gramsci’s use of the phrase in L’Ordine Nuovo, where it was repeated a few times with consistent reference to the problems of party organization. 11 When Gramsci first invoked “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will” in 1920, in Russia the party had already displaced the mass intelligence of the councils. Gramsci’s enthusiasm for the councils alongside his insistence on the rigidity of the vanguard party — the latter coming increasingly to displace the former in his thinking between the defeats in Turin and the formation of the Communist Party — registered a dilemma which he would later revisit and clarify in his Prison Notebooks. 12

What makes Gramsci so confounding to read and allows his writing to be so easily appropriated in irreconcilable ways is also potentially a source of great insight, if we understand the tensions in his thinking as aspects of a contradictory reality rather than merely extrinsic obstacles to interpretation. To understand Gramsci’s later deployment of the slogan, we will have to investigate the relevant concepts of the Prison Notebooks, informed by scholarship drawing on the critical edition; and to interpret what is theoretically and politically at stake in Gramsci’s evolving conceptions of pessimism and optimism, we have to examine the categories of “intellect” and “will” to which they are attached.

Intellect

A recurring theme in Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks is that all people are “philosophers,” or “intellectuals,” even though the division of manual and intellectual labor in society makes it such that only small groups of people are recognized as being capable of thought. 13 For the Gramsci of the Prison Notebooks, as long as this division existed, the task of those socially recognized as intellectuals would be to build a revolutionary culture and assume a revolutionary leadership: “there is no organisation without intellectuals, that is without organisers and leaders, in other words, without the theoretical aspect of the theory-practice nexus being distinguished concretely by the existence of a group of people ‘specialised’ in conceptual and philosophical elaboration of ideas.” 14

Yet at the same time, the role of political organizations would also be to cultivate mass “intellectualities.” 15 This peculiar term, which appears to be suspended between “intelligence” and “intelligentsia” in prevailing translations, throws the relation between the two into question. But despite its seeming obscurity, as Panagiotis Sotiris argues in a brilliant commentary, the notion of “intellectuality” refers us to very concrete “questions referring to organization and its role in the transformation of modes of thinking, in the confrontation with antagonistic ideologies, in the articulation of learning practices.” It refers us to the problems of the production of knowledge involved in the “elaboration of strategies.” 16

Gramsci’s conception of mass intellectualities reframes the question of political leadership. To follow another line of his reasoning in the Prison Notebooks, the fact that there are leaders and led is an inescapable fact of politics; but the question is whether leadership is oriented towards preserving this distinction for eternity, or generating “the conditions in which this division is no longer necessary.” 17 This is why, for Gramsci, “for a mass of people to be led to think coherently and in the same coherent fashion about the real present world, is a ‘philosophical’ event far more important and ‘original’ than the discovery by some philosophical ‘genius’ of a truth which remains the property of small groups of intellectuals.” 18

We have to distinguish Gramsci’s approach from those ideologies of so-called “Western Marxism” which revolve around consciousness. As Buci-Glucksmann points out, for these ideologies the intellectual’s “specific function” is to give the working class “its homogeneity, unity, and vision of the world.” In contrast, Gramsci’s “refusal of a potential dissociation between philosophical class consciousness and its real agent, the proletariat, rules out any problematic of the intellectuals that would transform them into the depositories of class consciousness (as in the young Lukács) or into guarantors of the critique of the capitalist mode of production.” This is why, she elaborates, for Gramsci it is not “the intellectuals as such who enable a subaltern class to become a leading and ruling class, a hegemonic class.” Rather, “this function is performed by the modern Prince, the vanguard political party as the basis from which the intellectual function has to be considered afresh, together with the relationship between research and politics, and their reciprocal tension.” 19

As Peter Thomas points out in his detailed and rigorous study of the Prison Notebooks, The Gramscian Moment, this was already what was at stake in the biennio rosso. L’Ordine Nuovo was “a paradigmatic experiment of young intellectuals who sought to redefine their relationship with the working class in active, paedagogical terms—a relationship in which they were more often the ‘educated’ than the ‘educator.’” 20

In his 1930 reflections in prison on the Turin experience, Gramsci responded to accusations that the movement was “spontaneist.” He replied by insisting on “the creativity and soundness of the leadership that the movement acquired.” It was not an “abstract” leadership, and “did not consist in the mechanical repetition of scientific or theoretical formulas.” Crucially, “it did not confuse politics — real action — with theoretical disquisition.” Rather, the leadership of the Turin movement “devoted itself to real people in specific historical relations, with specific sentiments, ways of life, fragments of worldviews, etc., that were outcomes of the ‘spontaneous’ combinations of a given environment of material production with the ‘fortuitous’ gathering of disparate social elements within that same environment.” This “spontaneity,” Gramsci argued, “was educated, it was given a direction.” The education and direction of movement sought “to unify it by means of modern theory,” but it did so “in a living, historically effective manner.” By speaking of the “spontaneity” of the movement, its leaders emphasized its historically necessary character, and “gave the masses a ‘theoretical’ consciousness of themselves as creators of historical and institutional values, as founders of states.” 21

Gramsci displaced the question of consciousness towards that of knowledge, and its material constitution in organizational forms. This is the originality of his reading of Lenin, which, Buci-Glucksmann emphasizes, he describes as “gnoseological.” 22 Thomas contrasts this explicitly to “epistemology,” which would be the abstract problem of the production of knowledge. “Gnoseology,” as Gramsci uses it, “refers more generally to the effective reality [Wirklichkeit] of human relations of knowledge.” 23

Gramsci’s reinterpretation of Leninism in terms of the effective reality of human relations of knowledge structures his understanding of the politics of the intellect. At a methodological level, Gramsci scrutinized the classical Marxist claim that people “acquire consciousness of structural conflicts on the level of ideologies.” This should be understood, he argued, “as an affirmation of gnoseological and not simply psychological and moral value.” Lenin’s “greatest theoretical contribution” to Marxism — the “theoretical-practical principle of hegemony” — had a “gnoseological significance.” Lenin, Gramsci wrote, “advanced philosophy as philosophy in so far as he advanced political doctrine and practice.” He located knowledge in what Gramsci called a “hegemonic apparatus,” which, “in so far as it creates a new ideological terrain, determines a reform of forms of consciousness and of methods of knowledge: it is a fact of knowledge, a philosophical fact.” 24

By embedding knowledge in the concept of the “hegemonic apparatus,” Buci-Glucksmann argues, Gramsci clearly differentiated the theory of hegemony from a pure theory of consciousness or culture. He underscored its material reality “as a complex set of institutions, ideologies, practices and agents (including the ‘intellectuals’).” This was not, however, the same thing as a liberal study of static institutions, “for the hegemonic apparatus is intersected by the primacy of the class struggle.” 25

Elaborating on this point, Thomas adds that “a class’s hegemonic apparatus is the wide-ranging series of articulated institutions (understood in the broadest sense) and practices — from newspapers to educational organisations to political parties — by means of which a class and its allies engage their opponents in a struggle for political power.” In the specific relations of force between classes, “a class’s potential for political power therefore depends upon its ability to find the institutional forms adequate to the differentia specifica of its own particular hegemonic project.” 26

The totality of Gramsci’s work points us, in other words, to the problem of finding new organizational forms, political parties which are “historical experimenters” with new kinds of knowledge. 27 In this regard Sotiris underscores the Gramscian image of the party as a “laboratory,” rather than “the general staff of the proletarian army.” Gramsci rather points us to “a political process for the production of knowledges, strategies, tactics, and forms of intellectuality.” Thus from Gramsci’s perspective the party is not a predetermined structure which would subordinate various social movements to its authority. It is rather the name for the laboratory in which, as Sotiris puts it, a “plurality of processes, practices, resistances and collectivities” can be unified into a “common hegemonic project,” a project which combines “new and original forms of struggle, of resistance, blockage, reappropriation and emancipation.” This “potential unification requires thinking the party or the organization as a laboratory producing intellectualities, strategies, tactics, but also as a hegemonic practice. It is a constant encounter between practices, experiences and knowledges.” 28

Let us bring this exegetical detour back to Gramsci’s early statement of “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.” It should be clear that Gramsci was in fact grappling, albeit in a hasty and triumphalist manner, with the tension between the underlying recognition that all people are intellectuals, and the conditions for politics in which those with the social function of intellectuals play a leadership role. The continuity of these questions in Gramsci’s evolving political thought form the essential context for understanding his deployment of pessimism and optimism in the Prison Notebooks, where it is most frequently encountered.

Will

To understand the reappearance of the phrase in the Prison Notebooks, we will turn theoretically from the intellect to the will, which is not only a key axis of the complex development of Gramsci’s thought, but also a pillar of the contemporary repetition of the slogan. Now, it seems, the phrase is meant to discourage us from dreaming of utopias, downplaying defeats, or dismissing dangers. But we would not want to give the impression that this emphasis on a sobering pessimism leads us to quietism and surrender. Optimism of the will then becomes the necessary supplement for something that is missing in the original pessimism; it allows us to be comfortable with pessimism, to disseminate pessimism to those who cling to illusions because they would otherwise be incapable of coping with the hopelessness that pessimism brings.

But this abstract assessment of sentiments rather obscures what was at stake for Gramsci as he repeated the phrase in his Prison Notebooks, where it represented a detailed and systematic reflection on the strategic and organizational questions of his revolutionary experience. The historical background has drastically changed: by 1926 revolutionary politics in Italy had been defeated and fascism had consolidated its rule. In his Prison Notebooks Gramsci was thinking through politics anew. As Buci-Glucksmann puts it, “after the failure of the revolution, and the consolidation of dictatorship, new strength can come only from knowledge.” 29

It was probably one footnote in the standard English volume, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, which popularized the slogan among Anglophone readers in 1971. The context was a discussion of the history of Italian politics and political thought written from 1930-32, in which Gramsci was reflecting on “the effectiveness of the political will” which has “turned to awakening new and original forces rather than merely to calculating on the traditional ones.” 30 His inspiration was Machiavelli, whose fundamental recognition that “politics is an autonomous activity” provided a necessary supplement to Marxism, which in conditions of defeat had the tendency to lapse into a mechanistic economic determinism. In its belief in the inevitable and predetermined coming of revolutionary conditions, this determinism resembled nothing more than a religious fatalism. 31

For Gramsci what was important about Machiavelli was his realization that the historical transformations announced by the Renaissance could not be achieved without the formation of a national state, and some historical agent was required which could represent the “collective will” and achieve this historical task — the Prince. 32 But the Prince was not an already-existing person; in writing The Prince, Machiavelli was trying to call this agent into being. He thus bridged between the preceding tendencies of political thought to either dream of utopias, or engage in disinterested scholarly analysis.

So Machiavelli’s “concrete will” to bring about a new order could not be reduced to utopias and daydreams, as skeptics like his aristocratic associate Guicciardini had charged. The skeptical attitude which dismissed any possibility for historical change had to be distinguished, Gramsci wrote, from a real “pessimism of the intelligence, which can be combined with an optimism of the will in active and realistic politicians.” 33

At this point the editors and translators of the Selections from the Prison Notebooks added a footnote referring to another portion of the notebooks from 1932, an independent fragment on “daydreams and fantasies.” Gramsci wrote that daydreams and fantasies were fundamentally passive, imagining that “something has happened to upset the mechanism of necessity,” and therefore “one’s own initiative has become free.” 34 As a political orientation this was in stark contrast to Machiavelli’s concrete will, which applied itself, he wrote elsewhere, to the “effective reality” and aimed at “the creation of a new equilibrium among the forces which really exist and are operative.” 35

Here he repeated the decisive phrase: “On the contrary, it is necessary to direct one’s attention violently towards the present as it is, if one wishes to transform it. Pessimism of the intelligence, optimism of the will.” 36

This language is striking, yet incomprehensible without understanding the way Gramsci was using Machiavelli to elaborate on the problems of revolutionary strategy that had preoccupied him before prison. Machiavelli, embedded in his particular historical moment, represented the formation of a concrete will “in terms of the qualities, characteristics, duties and requirements of a concrete individual.” For Gramsci, the “modern Prince” — which had the historical task of bringing about the alliance between the proletariat and the peasantry that would be capable of initiating the process of transition to a workers’ state — could not “be a real person, a concrete individual.” It rather had to be “a complex element of society in which a collective will, which has already been recognised and has to some extent asserted itself in action, begins to take concrete form. History has already provided this organism, and it is the political party — the first cell in which there come together germs of a collective will tending to become universal and total.” 37

Thus for Gramsci the pessimism of the intellect constituted the refusal to conceive of politics in terms of the ahistorical dreams of utopias. This did not mean simply resigning oneself to the equilibrium of the effective reality: optimism of the will was the application of the autonomy of politics to the really existing and operative forces which could bring about a new equilibrium. But this will was not simply a matter of individual determination; it was nothing other than the party, whose organizational processes brought about the formation of a concrete and collective will.

As Sotiris writes, Gramsci’s reflection on Machiavelli “encapsulates the necessity of the political party, in opposition to other forms of organization exactly on the basis of a need not only to form a collective will but also to enable it to articulate and execute a political project.” Just as Machiavelli “sought the person that could function as the catalyst for a process of national unification of the fragmented Italian space, and the modern political party,” Gramsci believed that the communist party “should also function in this unifying way, articulating the fragmented and ‘molecular’ practices and aspirations of the subaltern in a common political demand for radical transformation..” Thus Gramsci treated the communist party as “the terrain par excellence for the elaboration of a collective will capable of being the protagonist of a process of social transformation.” 38 But as Thomas points out, while Gramsci saw the political party as “the historically given form in which the decisive elements of organisation, unification and coordination had already begun to occur,” the re-elaboration of this form into a “non-bureaucratic instrument of proletarian hegemony” would require “an ongoing dialectical exchange with the popular initiatives from which the ‘modern Prince’ could emerge and into which it would seek to intervene.” 39

Let us recall that these reflections on the possibility of organization were taking place under conditions of defeat. It is in this context that Gramsci brought the strategic and organizational question of the party towards the problem of politics as an autonomous activity. As Thomas writes, “the ‘modern Prince’ for Gramsci, imprisoned for being a member of a Communist party, was a collective body constituted as an active social relation of knowledge and organisation” which could initiate the formation of a collective will. But “just as its Machiavellian predecessor, Gramsci’s ‘modern Prince’ remained no more than a proposal for the future, not a concrete reality, in his time—or in our own.” 40

In this very concrete sense Gramsci is our contemporary. What we miss in reducing “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will” to a sensibility is the practical importance of Gramsci’s reflections. In the absence of an organizational form which can operate as the organizer of a concrete and collective will, politics has become unavailable to us. To recall Gramsci’s formulation, we require theories and practices of organization which are oriented towards awakening new and original forces, rather than calculating on the traditional ones.

Ethics

We cannot entirely separate the organizational question of politics as autonomous activity, which runs continuously from L’Ordine Nuovo to the Prison Notebooks, from what we might call the ethical disposition of those who participate in politics. However, these problems of ethics should be distinguished from the psychological and moral level, which is also the level of consciousness, that Gramsci clearly demarcated from the gnoseological. Gramsci’s writings propose new ethical principles, each marked by fundamental lines of demarcation, which appear in passages which were not included in the initial English translation (but made available in the larger edition edited by Pete Buttigieg’s father Joseph), and in his letters.

In a portion of a longer passage from 1929-30, Gramsci wrote that Marx’s “catastrophism” was a valid reaction to “the general optimism of the nineteenth century.” Marx “poured cold water over the enthusiasm with his ‘law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall.’” Gramsci criticized the optimistic tendency to imagine utopias, which led people to fantasize about “easy solutions to every problem.” “All the most ridiculous daydreamers,” he wrote, “descend upon the new movements to propagate their tales of hitherto unrecognized genius, thereby casting discredit on them.” Instead, he said, “it is necessary to create sober, patient people who do not despair in the face of the worst horrors and who do not become exuberant with every silliness. Pessimism of the intelligence, optimism of the will.” 41

In another independent fragment in the notebooks from 1932, titled “Optimism and pessimism,” he noted that “optimism is nothing more than a defense of one’s laziness, one’s irresponsibility, the will to do nothing,” and is therefore “also a form of fatalism and mechanicism.” Optimism meant relying “on factors extraneous to one’s will and activity.” What was necessary instead was a reaction which took “the intelligence for its point of departure.” Gramsci rejected the enthusiasm resulting from the exaltation of factors extraneous from one’s will and activity, which was “is nothing more than the external adoration of fetishes.” And yet, there was also a “justifiable enthusiasm,” which could only be “that which accompanies the intelligent will, intelligent activity, the inventive richness of concrete initiatives which change existing reality.” 42

We cannot avoid noticing that the binary oppositions of the slogan have been displaced. There is an optimism tied to the “will to do nothing,” which is contrasted to an “intelligent will.” A certain kind of “optimism of the will,” then, is not only the counterpart of fatalism and mechanicism, but also a form of utopian daydreaming. This is not simply because pessimism is needed to correct the optimism of the will. The alternative Gramsci actually describes is instead a fusion of intelligence and will, the “intelligent will,” which is accompanied by a justifiable form of “enthusiasm.” With this he recalls the slogan printed in a box under the title from the very first issue of L’Ordine Nuovo: “Educate yourselves because we will need all your intelligence. Rouse yourselves because we will need all your enthusiasm. Organize yourselves because we will need all your strength.” 43 Enthusiasm is the first new ethical principle.

In a 1929 letter to his brother Carlo, in which he recalled the experience that both of his brothers had in conditions of war, Gramsci reflected on hardship and deprivation and rejected “those vulgar, banal states of mind that are called pessimism and optimism.” His state of mind, Gramsci said, “synthesizes these two emotions and overcomes them: I’m a pessimist because of intelligence, but an optimist because of will.” He claimed that “in all circumstances” he thought “first of the worst possibility in order to set in motion all the reserves of my will and be in a position to knock down the obstacle.” At the same time, he said, “I have never entertained any illusions and I have never suffered disappointments.” But he did not end by reiterating the slogan. He shifted, instead, to different words: “I have always taken care to arm myself with an unlimited patience, not passive, inert, but animated by perseverance.” 44

Perhaps between the Prison Notebooks and this letter, the gnoseological level and the psychological and moral level appear to be conflated. Here Gramsci does not appear to be speaking of knowledge which is embedded in the hegemonic apparatus, the organizational level of the formation of the concrete and collective will. Yet these letters cannot be reduced to a mere indication of Gramsci’s psychological and moral state; his personal situation is precisely the historical and political condition of defeat he set out to theorize, defined by the political void that no modern Prince was available to fill. If we rush quickly to conflate the psychological and moral with the gnoseological, we run the risk of abstracting the personal will, in the manner that Gramsci criticized in his notes on daydreams, by detaching it from the organizational processes that can actually form a concrete and collective will.

Despite beginning with the oppositions between pessimism and optimism, intellect and will, in this letter Gramsci in fact redirects them towards “perseverance,” a unitary category which is tied not to optimism or pessimism, but to “patience.” In a certain form, Gramsci wrote in a 1930-32 note, perseverance is enabled by the mechanistic philosophy of history: “For those who do not have the initiative in the struggle and for whom, therefore, the struggle ends up being synonymous with a series of defeats, mechanical determinism becomes a formidable force of moral resistance, of cohesion, of patient perseverance.” It allows one to say: “I am defeated, but in the long run history is on my side.” In other words, this kind of perseverance is an “‘act of faith’ in the rationality of history transmuted into an impassioned teleology that is a substitute for the ‘predestination,’ ‘providence,’ etc., of religion.” However, Gramsci argued that despite this belief in mechanical determinism, in reality “the will is active; it intervenes directly in the ‘force of circumstances,’ albeit in a more covert and veiled manner.” When those who are accustomed to being defeated become historical protagonists, “the mechanistic conception will sooner or later represent an imminent danger, and there will be a revision of a whole mode of thinking because the mode of existence will have changed.” 45

Revising the note in 1932-33, Gramsci emphasized that it was never really the case that the subaltern was inactive; in fact, “fatalism is nothing other than the clothing worn by real and active will when in a weak position.” This is why it was necessary to “demonstrate the futility of mechanical determinism,” which “as a naïve philosophy of the mass” could be “an intrinsic element of strength,” but would, if “adopted as a thought-out and coherent philosophy on the part of the intellectuals,” become “a cause of passivity, of idiotic self-sufficiency.” This happens when intellectuals “don’t even expect that the subaltern will become directive and responsible”; but in fact, “some part of even a subaltern mass is always directive and responsible.” 46

Hence perseverance cannot be a political principle if it is attached to future prophesy, but rather embodies the patient capacity to recognize the active will that persists beyond one’s personal psychological and moral state; it requires patience, and also courage. In a 1930-32 notebook entry on “Military and political craft,” Gramsci observed that “staying for a long time in a trench requires ‘courage’ — that is, perseverance in boldness — which can be produced either by ‘terror’ (certain death if one does not stay) or by the conviction that it is necessary (courage).” 47 Perseverance is the second new ethical principle.

Perseverance is irreducible to the level of the individual, because it is at this level that, as Gramsci was ultimately forced to conclude, the dialectic of pessimism and optimism breaks down. In a letter to his sister-in-law Tatiana Schucht in 1933, months after Hitler’s appointment as chancellor of Germany, Gramsci revisited his slogan. “Until a while ago,” he wrote, “I was, so to speak, pessimistic in my intelligence and an optimist in my will.” But he could no longer sustain his synthesis of pessimism and optimism: “Today I no longer think in this way. This does not mean that I’ve decided to surrender, so to speak. But it means that I no longer see any concrete way out and I no longer can count on any reserve of strength to expend that I can draw on.” 48 His body failing him, he saw no escape from his prison cell.

Without an organized, collective body to sustain it, the individual body falters. When the political condition of the party can no longer be taken for granted, and optimism of the will has become a daydream, pessimism of the intellect does not yield knowledge. We are required instead to persevere in the interregnum between the previous moments of emancipatory possibility and the unachieved discovery of a new concrete hegemonic political form.

Both perseverance and enthusiasm have to be separated from mechanicism and fatalism, and refer instead to the concrete will that applies itself to the effective reality. In order to do so, they must be based in the collective body, and not the individual consciousness. As psychological and moral categories, both pessimism of the intellect and optimism of the will run counter to the ethical disposition that is articulated in the margins of Gramsci’s text.

Pessimism of the intellect confirms itself in the experience of defeat, severing the personal body from the collective body which is required for us to persevere. Persevering in politics is difficult, and requires a patient and courageous commitment which does not depend on forecasts of the future.

Optimism of the will obscures the problem of organizational forms and forecloses their enthusiastic investigation. It means clinging to traditional forces, rather than creating and organizing new ones, and is thus incompatible with the intelligent will which is defined by enthusiasm for concrete initiatives which can change the existing reality.

Enthusiasm and perseverance emerge as Gramsci’s ethical principles. But now it is time to conclude, by revisiting pessimism and optimism.

Reversal

I believe that our current moment shows us that Gramsci’s insights are not well represented by the slogan, “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.” In fact, we will better understand our situation if we precisely reverse it.

Optimism of the intellect, because we have to start by recognizing that all people are capable of thought, that they are able to not only form conceptions of the world but also to experiment with new possibilities. There is no emancipatory politics without recognizing this universal capacity for thought. Gramsci never failed to emphasize two essential points: that all people are philosophers, and that this mass intelligence is the basis for a future society; and that despite the political division between leaders and led, rulers and ruled, it is possible to engage in forms of political action which abolish this distinction rather than preserving it. This is quite distinct from an optimism about the future, regarding which we must pass over in silence. Our optimism of the intellect is the one which says that it is possible for people to govern themselves, and in every act of collective resistance this capacity is confirmed.