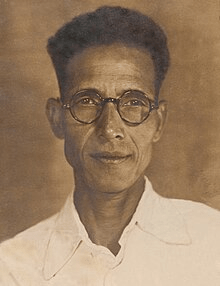

R.B.More

K K Theckedath

AS we approach the 120th birth anniversary of Comrade Ramchandra Babaji More (on March 1, 2023) it would be important to understand the relevance to the present dalit movement of this first revolutionary among the depressed classes who joined the Communist Party in Maharashtra way back in the twenties of the last century.

In the recently held national executive meeting of the Dalit Shoshan Mukti Manch on July 17-18, 2022, among the 14 tasks underlined in the annual plan, the first is to use the celebrations of Dr B R Ambedkar’s birth anniversary on April 14 and utilie it to propagate against the caste system. The second task suggests the organisation of programmes commemorating the legacy of Comrade R B More.

As regards Dr B R Ambedkar, he has been described using a string of adjectives, one of which is Kranticha Surya. These are all apt descriptions of this great liberator of the down-trodden. He continues to inspire all those who work in the left and democratic movement. It may be useful to remember how Comrade R B More himself described Dr B R Ambedkar. In a letter to the Polit Bureau of the Communist Party dated December 23,1953, entitled ‘On untouchability and the Caste system’ he writes: “Along with the British Raj came bourgeois democratic ideology in our country and it began to fight the old feudal ideology. Stalwarts such as Raja Rammohan Rai, Mahatma Phule, Ranade, Agarkar, Mahatma Gandhi and Dr B R Ambedkar have fought this social reaction with vigour and have no doubt weakened it greatly. So far as the struggle against untouchability is concerned, Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar’s role is, of course, most militant and most uncompromising. He alone pointed out that the root cause of untouchability is the varna vyavastha and the caste system which must be wiped out lock stock and barrel. He attacked ruthlessly all the old Hindu scriptures mercilessly, and no wonder he became a Messiah in the eyes of the most downtrodden masses of the untouchables” … “Yet with all his limitations it must be said that he and his methods are absolutely free from anything of humanitarianism and sentimentalism. He roused the untouchable mass, he created in them a feeling of self-respect and taught them to fight for their human rights and social equality. He shifted the problem of removal of untouchability from the plane of begging and appeals to the plane of assertion and struggle.” (Biography of R B More by Satgyendra More).

RAMCHANDRA MORE – A STELLAR FIGURE

Coming to R B More, although he was one of the first and most ardent followers of Dr Ambedkar, and was personally responsible for persuading Dr Ambedkar to visit the town of Mahad in coastal Maharashtra for the historically famous Chaudaar Talav (Tale Satyagriha) of 1927, yet he is not to be counted merely as a follower of Dr Ambedkar, shining in the glory and reflected light of the master. He was himself a brilliant star, effulgent with its own internal energy. He was the one to realise the limitations of Dr Ambedkar’s movement, and to give it a linkage with the strategically important working-class movement and its philosophy. He was one of the first dalits from Maharashtra to join the Communist Party way back in 1928. In the struggle of the dalits for liberation he should be considered as one of the key figures to inspire our youth.

R B More’s early life, like that of Dr Ambedkar, is linked up with the English education that his father received in the British army as a part of the Mahar regiment. The Mahars were a caste of untouchables, who traditionally worked with dead cattle and skinned the carcasses.

As Marx had said, “England has to fulfil a double mission in India, one destructive, the other regenerating- the annihilation of the old Asiatic society, and the laying of the material foundations of Western society in Asia.”

In recruiting men for the army, the British had realised the native resilience and courage of the Mahars. They were recruited in large numbers to form the Mahar Regiment. The British were amply rewarded when, in the Battle of Bhima-Koregaon, between the British and the Peshwas on January 1,1818, a mighty army of the Peshwas numbering over ten thousand was defeated by the Mahar Regiment of only nine hundred men.

The recruits in the army were given training and education in English, geography and science up to the matriculation standard. The liberating influence of this process can be seen in the dalit history of Tamil Nadu. Even before there was an organised movement of the untouchables, and even prior to the arrival of leaders like E V Ramaswamy Naikar, or the rise of the Dravida movement, thousands of Nadars (Shanars) had embraced Christianity. “This helped them, to access English education and the resultant empowerment” (See K A Manikumar, A social movement in the nineteenth century south Tamil Nadu, Social Scientist, March-April 2022).

In the mid-nineteenth century More’s grandfather Shivram and his brother Tanaji had to leave their village, Lonere in Kolaba (now Raigad), a coastal district of Maharashtra, in search of livelihood. After struggling with many types of jobs, like laying the roads, breaking stones, they were moving from place to place until they reached Khandala where railway lines were being laid. Here they came across a recruiting agent promising jobs in Mauritius. Tanaji took up a three-year contract as bonded labour and left for Mauritius. Shivram came back and settled down in a the town of Dasgaon in Raigad, ten miles away from Mahad. Being a port town off the Arabian sea, there were contacts with the Mahar soldiers on holiday who would alight there to proceed to their villages in the interior. This was the basis for his getting English education.

Shivram’s son Babaji (Ramchandra’s father) educated his sons, Laxman and Ramchandra. Laxman was given education up to standard seven, and he became the first dalit school master of the area and was appointed in a school in Tudil village. His monthly salary was seven rupees. Young Ramchandra More grew up in a rural setting in the group of houses of the village, known as the Maharwada, especially meant for the low caste Mahars. However, his brilliance in his studies at school made his caste brethren to look up to him for all their problems.

Two examples of Ramchandra’s brilliance as a young man may be given. It was suggested to him by his sympathetic upper caste school master that he should sit for a scholarship examination. This examination was in September 1914 when Ramchandra was 11 years old. He had to travel to Alibaug, the headquarters of the district. In his autobiographical note, R B More writes about the strict observance of untouchability in Alibaug. He was not allowed to sit with the other candidates but was made to sit on a separate wooden box outside the class room, and the question papers were tossed to him so that pollution by touch was avoided!

But the important thing is that out of the 200 candidates who appeared, Ramchandra stood first. He became eligible for a scholarship of five rupees per month. This was a considerable amount, compared to the salary of a teacher. Ramchandra was entitled by this scholarship to study in the government run English school at Mahad. However, the headmaster and other teachers refused to grant him admission on the ground that the school was being run in a rented house which belonged to a Brahmin family. If the admission was to be given to a dalit student, the school would have to quit from the premises.

Ramchandra came back to his village and started working with the others, tending the cows and looking after other jobs along with his cousins. One day two social workers who had come to the village heard about this. After meeting Ramchandra and getting to know the details they suggested to him that he should make his complaint public. They wrote out a message on a postcard and also wrote an address on it. Ramchandra signed it and sent the letter as suggested.

The news got published that in a government run school a brilliant Mahar was denied admission. This had the desired effect. The headmaster called him and gave him admission. However, the condition for admission was that he should sit separately as an untouchable.

So Ramchandra attended school on all the days, with the exception that, on days on which the subjects of drawing and drill were taken, he should not attend school. These were periods when the risk of touching and pollution were maximum. The time that Ramchandra was to spend outside the school was utilised by Ramchandra to roam the roads in the town of Mahad.

We now come to the second example of his brilliance. While interacting with the common people of Mahad and his Mahar brethren he came to understand the problems of the Mahar army pensioners who had to visit Mahad and spend considerable time in the town. Drinking water was not available to them in any of the hotels. Water was obtained by these hotels by paying one paisa per bucket, and no free water was available to the Mahars, since there were banned from the hotels.

When Ramchandra visited his own village in Dasgaon he discussed this matter with his Mahar friends. He convened a meeting in his Maharwada to discuss this problem. Mahars from neighbouring Maharwadas also attended. At this meeting he suggested that a hotel should be opened in Mahad town where one could serve tea for one paisa, and where water would be free for all and especially for the Mahars.

Thus, the first hotel owned by a Mahar was opened in Mahad town. The owner was one Mohaprekar. This hotel not only gave free water to every Mahar who came to Mahad town for work, and tea at one paisa, but provided a place for R B More to meet his caste people and prepare official applications in English and have other discussions with them. More important was that it became a centre for meetings and a nucleus for the future organisation of Mahars for their rights.

When, later, an upper caste zamindar, one Deshmukh, tried to evict the owner by registering false cases against him, More took up the hotel himself and ran it with the signboard, ‘R B More’s Vishranti Griha’. This great and potentially progressive step was initiated by a teen age youngster who was not allowed to attend the drawing and drill classes in his school for fear of pollution!

R B More’s brief autobiographical tract is reproduced in the book ‘R B More -a strong link between the dalit and the communist movements’, written by his son, Satyendra More. In this piece he writes about his struggle to get education. After three years, when his scholarship expired, he was forced to give up his education. He discovered that the scholarship money which was sent to him had been taken by his paternal uncle with whom his mother had been living after his father’s death. A detailed account of how he ran away from home to Pune, and to Khidki, where he took admission and worked on the side, his tiff with the temple authorities who had hired his bhajan mandali to perform, but made them to sit far away from the temple as they were untouchables, his visit to Mumbai to attend the funeral procession of Bal Gangadhar Tilak in August 1920, his being mislaid and robbed in Mumbai, his working in the docks as headload worker to enable him to go back to Khidki, and his final settling down in Dasgaon to finish his education, are all described in an objective and self-critical fashion.

S K BOLE RESOLUTION

In 1923, news came that Rao Bahadur Sitaram Keshav Bole had got a resolution passed in the Bombay Provincial Legislature to get all public places like government offices, water tanks etc., open to all, including the untouchables. More describes it as a positive aspect of the British rule in India, that an elementary human equality had been ushered in by them.

As soon as More came to read about this, he called a meeting of his caste brothers in his Maharwada. This meeting was also attended by dalits from other nearby villages. Here a proposal came from a cobbler (a Chambar) named Maruti Agwane that they should call a meeting to be chaired by Dr B R Ambedkar in the town of Mahad to press for the implementation of the 1923 Act. This was accepted by the meeting.

Earlier, in 1915, when he was only twelve years old, Ramchandra had seen Dr Ambedkar briefly. Dr Ambedkar had returned from Columbia university after his MA and PhD and was being given a reception by the Mahars in Mumbai at a place called Civil Lines near Crawford market. More was in Mumbai visiting one his relatives at this place. His political sense even at that age made him insist that he should be taken to this meeting.

What he saw made a deep impression on him. Dr Ambedkar refused to make a speech, but interacted informally with the people who had assembled and thanked them. It was Dr Ambedkar’s modesty that made an unforgettable impact on More.

Later in life, when he used to draft applications for his Mahar brethren, and even for others who would come to the hotel, some Brahmins and Gujars would tease him and say “Ramchandra should become a lawyer or a mamlatdar”. To this Ramchandra used to reply, do not make fun of us. “Do you know that one of us, Dr B R Ambedkar, has become an MA, PhD, DLitt, and Bar-at-Law?” This was the Ambedkar that More was to invite to Mahad.

More closes his autobiographical tract by noting how, even physical conditions and changes were leading to situations where the Mahars would assert their rights. One example he mentions the opening of road transport service between Mahad and Dharamtar town, which was on the Mumbai-Mahad road. Private vehicles plying between the towns refused to allow the untouchables to travel by their buses. More initiated a signature campaign against the owners of these vehicles. The memorandum was sent to the district collector. This officer happened to be an Englishman who had handled More’s earlier complaint about his school admission. He wrote back that the matter would be rectified. This settled the matter, and the untouchables were allowed to travel by private vehicles.

PREPARING FOR DR AMBEDKAR’S VISIT

In the vacation of May 1924, the 21 year- old More went to Mumbai, took the help of a senior social worker Anantrao Chitre, and visited Dr Ambedkar in his office at Parel. Dr Ambedkar was very co-operative and agreed in principle to visit Mahad, but did not specify any date.

In his autobiographical note More describes his efforts to collect men and material for the promised visit of Dr Ambedkar to Mahad. He narrates his experience in organising the first charity show of the play ‘Sant Tukaram’ at Damodar Hall, Parel, and how he managed to sell tickets to the Mahar residents of the Military Civil Lines in Mumbai. However, in spite of all his endeavours, and repeated visits to Mumbai in the May and October vacations, as it turned out, it was only three years later, in March 1927, that this conference and satyagriha at the Chawdaar Tale took place.

In the meanwhile, the S R Bole resolution of 1923 and Act on the use of water from public tanks and entry into all public spaces had caught the imagination not only of the untouchables but also of the young and progressive people of the district. In the trading town of Goregaon in Mangaon Taluka, which was the home town of the renowned trade union leader N M Joshi, a group of upper caste people were explaining the provisions of the Act to the Mahars and Chamars. It was decided that they would symbolically[K1] [K2] implement the Act by drawing water from the town tank. One of the dalit leaders, Ramchandra Chandorkar, even entered the water tank.

This incensed the Marathas and other non-dalit groups, who launched a large-scale attack on dalit houses and caused damage to property. These dalits wrote to the Mahar Samaj Seva Sangh, Mumbai.

More, who was in Mumbai at that time, took the initiative to call a meeting of the Sangh, get a resolution condemning this attack, and give a call for funds to help the victims. He took the funds personally to Goregaon, met the victims and disbursed these funds.

He also resolved to have a similar demonstration in his own Dasgaon town. He requested Ramchandra Chandorkar to accompany him to Dasgaon. He convened meetings to explain the issues in the Bole resolution and to decide on a date for holding a demonstration in the town.

Accordingly, a meeting was held at the dharmasala ground in Dasgaon on December 4,1926. Between 200 and 300 people, including dalits from nearby towns of Goregaon, Vahu and Sape, attended this meeting. More had taken care to involve the non-dalit leaders also in this programme. In fact, the chairman of the meeting was a non-dalit leader. After the speeches were over, there was a systematic and symbolic partaking of water from the public water tank.

Surprisingly, this programme went off peacefully, since More had planned it well and taken care to see that there was wide campaigning prior to this, with handbills and small meetings. This shows the skill of this developing leader of the working class. This event took place full three months before the famous Mahad Satyagriha on March 19-20, 1927, where Dr Ambedkar led over five thousand dalits to the Chawdaar Tale (lake). Ramchandra More’s age was 23 years.

Following the events of the historic satyagriha on March 20,1927 and in the course of the following protest demonstration in December of the same year where the hated Manusmriti was burned in a public meeting of thousands of followers, gradually Dr Babasaheb realised that capabilities and honesty of this young worker in the cause of the untouchables.

Ramchandra became a chosen confidante and co-worker of Dr Ambedkar. He was requested stay with him in his house in Naigaum at Parel in Mumbai. Ramchandra moved to Mumbai and started staying with Dr Ambedkar. He used to help him in bringing out his journal, as well as in other work. Many were the days when they would both get out of the house together, have (bread) slice-maska and tea as breakfast at the neighbouring Irani restaurant, Dr Ambedkar would take a tramcar and go to court for his legal work, and More would come to the office to tend to the journal work and other organisational jobs.

to be continued in next issue of PD.

The Relevance of Comrade R B More to the Dalit Movement-II

K K Theckedath

BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR AND THE COMMUNISTS

BEFORE joining the Communist Party More had a series of discussions with Babasaheb Ambedkar. He was trying to explain to Dr Ambedkar about the nature of the communist movement and the advantages for the dalits from such a movement. Finally, Dr Ambedkar said that he would not come in the way of his joining this mighty struggle of mankind. He only expressed the hope that Ramchandra would find a respectable place in the Communist Party whose leadership could be described as “Bamananchi pudharipan” (leadership of the Brahmans).

Dr Ambedkar continued to have great respect for Ramchandra More, and later when elections to the Bombay provincial Council were to be held, he offered a ticket from his newly formed political party for More to contest. When More politely refused to contest on behalf of this party, Dr Ambedkar said that the offer was open even if More remained in the Communist Party: “Tu tujha paksha sodla nahis tareehi mi tula ubha karavayas tayar aahe.”

It is often extrapolated from isolated facts of history that Dr Ambedkar was against the communist movement. In fact, anti-communist intellectuals have an axe to grind in keeping the nascent and potentially powerful dalit movement from joining the rising communist current. However, in trying to hurry up and repair the chasm created by such propaganda, some communist writers have also done some unwarranted “self-criticism”.

One example given in such self-criticism is that the communists had kept away from the Kala Ram Mandir temple entry satyagraha in Nashik. A cursory examination of facts would show, however, that the decision to start the temple entry satyagraha at Kala Ram Mandir was taken in October 1929, just before Dr Ambedkar had to sail for England to attend the Round Table Conference. Our intellectual critics forget that on March 20, 1929, in a sweeping spell, the British arrested thirty-one top communist leaders from all over the country in the infamous Meerut Conspiracy case. These included the following eleven leaders from Mumbai, the city bearing the brunt of this imperialist attack: S A Dange, S V Ghate, K N Joglekar, Dr G Adhikari, R S Nimkar, S S Mirajkar, Shaukat Usmani, M G Desai, S H Jhabwala, G R Kasle and Arjun Atmaram Alve. It must be placed on record that of the four entrances of Kala Ram Mandir, the satyagriha at the East Entrance was manned by a group under the leadership of Kachru Mathuji Salvi. It may also be noted that in Mumbai R B More organised several meetings in support of the satyagriha and collected funds for it.

As regards the criticism that the communists were not sensitive about the discrimination against the untouchables being practiced in the mills, the above-mentioned demand number 9 in the strike of 1928 gives the lie to this accusation. The British journal ‘Labour Monthly’ has recorded this, but our anti-communist intellectuals fail to notice this demand in the bitterly fought six-months long strike of 1928.

In fact, with his deep understanding of the sufferings of the untouchables and his vast reading of political science and philosophy, to imagine that Dr Ambedkar would be against the communists is puerile to say the least. His radical economic ideas, including state socialism, nationalization of the land, the government providing housing to the untouchables and the poor, the eradication of the obscene levels of inequality in the country, against which he had warned in his address to the Parliament while speaking about the Constitution, all point to a close approach to Marxism.

In fact, seeing the results of the 1952 general elections, and the wave in favour of Jawaharlal Nehru, Dr Ambedkar made a very important statement in a letter to his close friend and a leader of the dalit movement, Karmaveer Dadasaheb Gaikwad. Dr Ambedkar had realised during the last phase of his life that his own political philosophy was incomplete in some fundamental way.

I quote from the biography of Dadasaheb Gaikwad written by Haribhau Pagare

“Babasaheb pudhe lihitat:

‘Mala Federation madhun bahar padavese vatate. Evadhech navhe, tar rajkaranatun ata poornatah nivrutta vhavese vatate. Te evadhe sope nahi, he mala mahit aahe. Tareehi majhe rajakeeya tatvajnan aaplya lokanche agdi twarit kalyan sadhu, ase mala vatat nahi. Majhya shivai kunalahi aaplya lokanchi kiti halakhichi sthiti aahe he mahit nahi. Tevha tyanche kalyan sadhanya sathi tari aankhi kiti divas vat pahavi? Communist Partyith jave, ase majhe mat hot chalale aahe.’ ” ( Haribhau Pagare, Dadasaheb Gaikwad- Jeevan va Karya, 1987,pp 244-245).

This meant: “I feel like coming out of the Federation. Not only this, I now feel like taking total retirement from politics. I know that this is not so easy. However, I do not feel that my own political philosophy will be able to bring immediate relief (welfare-kalyan) to our people. No one other than me can understand how extreme and desperate is the situation of our people. Therefore, how many days more should we wait to obtain relief for them? I am coming to the opinion that I should join the Communist Party.”

It is important to note that Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar had come to this conclusion, namely, about the incompleteness of his political philosophy, in 1952, even after he had been a key figure in the drafting of the Constitution of India, and after this constitution had come into effect in 1950.

R B MORE’S CRITICISM AND THE DALIT QUESTION

In his 1953 letter to the Polit Bureau of the Party, More made the following assessment of Dr Ambedkar’s political philosophy and its weakness:

“Yet it must be borne in mind that Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar’s influence in bourgeois ideology, in the final analysis, made him refuse (he has refused) to take into consideration the economic side of the problem in a revolutionary way.” (Satyendra More, p 281).

To understand the economic exploitation inherent in caste oppression we must consider Marx’s idea of surplus value in capitalist society and surplus produce in much earlier forms of society. In human social evolution it was the discovery of agriculture as a form of production, and the immense productivity of this form, that opened up the possibility of surplus produce. In the field of agriculture, ten persons’ labour could produce much more than what ten persons needed for sustenance. Prior to the discovery of agriculture, there was no slavery as we understand it. Indeed, “after examining the social institutions of as many as 425 primitive tribes, the sociologists Hobhouse, Ginsberg and Wheeler came to the conclusion that slavery was non-existent among primitive people who were ignorant of agriculture or cattle raising.”

In Capital Volume I, published in 1867, Marx makes this idea of the relation between land ownership and relations of oppression and exploitation clearer. In the last chapter of the book, he refers to one Mr Peel, who “took with him from England to Swan River, West Australia, means of subsistence and of production to the amount of 50,000 pounds. Mr Peel had the foresight to bring with him, besides, 3000 persons of the working class, women and children. Once arrived at his destination, Mr Peel was left without a servant to make his bed or fetch him water from the river. Unhappy Mr Peel who provided for everything except the export of English modes of production to Swan River!”

Three pages later, Marx gives the following statement: “Where land is very cheap and all men are free, where every one who so pleases can easily obtain a piece of land for himself, not only is labour very dear, as respects the labourer’s share of produce, but the difficulty is to obtain combined labour at any price.” (Marx,Vol I page 719).

It was the genius of the Indian exploitative system in general that it invented a special mode of production involving the caste system, which was extremely stable, and could stand its ground for thousands of years through the rule of the Moghuls, the Marathas, the British, and the Indian bourgeoisie with its so-called land distribution.

The simple idea was to deny through legislation and tradition the right to own or buy land or indulge in agriculture to a large section of the people, namely, the conquered tribes and groups. These were the untouchable castes. The word ‘jati’ for caste, as well as for describing the tribals as ‘janajati’, gives the key to understanding the social formation underlying this.

R B More’s first criticism points out that land possession is the key to the cause of dalit liberation. The slogan of immediate nationalisation of all land does not help in this democratic task, but the immediate distribution of land to all the dalits would be the correct slogan today.

THE SECOND CRITICISM OF R B MORE

To deal with the issues in a revolutionary way means to recognise the class nature of society, and of bourgeois democracy and constitution, as well as to note that social changes are to be brought about through the engine of class struggle. This involves recognising that in any region (village) the dalits are in a miniscule minority, and are generally dependent on the upper castes, and the general population, for their livelihood. The often reported ‘boycott of dalits’ is a weapon with the majority of the population who want to impose their will on the dalits.

Hence it is important to recognise the fact of their belonging to the class of landless labour. After all, they form a reservoir of unfree, servile and landless labour available for work at the lowest cost to peasants as well as superior landlords.

Moreover, what is the character of the agricultural labour class in India? Of the so-called farmer suicides recorded in Maharashtra in 2020, half were of landless labour. Out of the recorded 10,677 deaths, 5,579 deaths were of cultivators and 5,098 were of agricultural labourers. Out of the agricultural labourers 49 per cent belong to the dalit and adivasi populations.

As regards the landlessness of the dalits, the National Sample Survey office reports that in 2013, the 58 per cent of all rural dalit households were landless. The list of the top three states in this regard, Haryana (92 per cent), Punjab (87 per cent) and Bihar (86 per cent), shows that landlessness among dalits has been a feature of agricultural development in India even after 66 years of independence.

Thus, the need of the hour is to recognise the commonality of interests of agricultural workers’ unions and the dalit movement, and to link the dalit movement with the movement of the landless agricultural workers, and in a reciprocal relationship, strengthen the struggles of Dalits as well as of agricultural workers.

These are the conclusions to be drawn from the observations of Ramchandra Babaji More. The inspiration and fire power comes from the example of Dr B R Ambedkar, but the direction for movement for the present situation comes from the life of Comrade R B More. Truly, let us celebrate his life and make his views known to all those who struggle for justice for the dalits.

(Concluded)

Leave a comment