By Marissa Block | May 19, 2022

This article was originally published on progolfnow.com and has been republished here with permission.

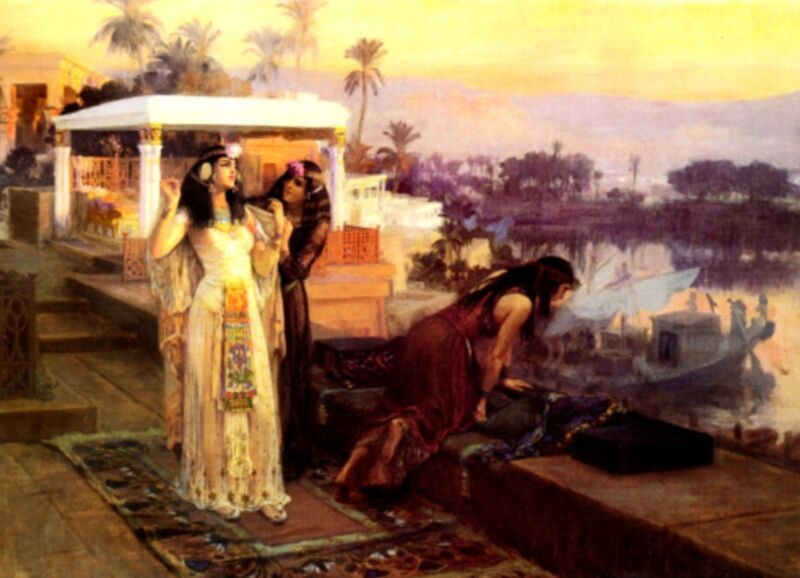

Shah Jahan’s 3d wife, Mumtaz Mahal, made him refuse his polygamous rights. She gave birth to 14 children and died at only 37 during the delivery of their last one. Her tomb was the Taj Mahal, and the events that followed her death were creepy, violent, and offensive to her legacy – here’s the story.

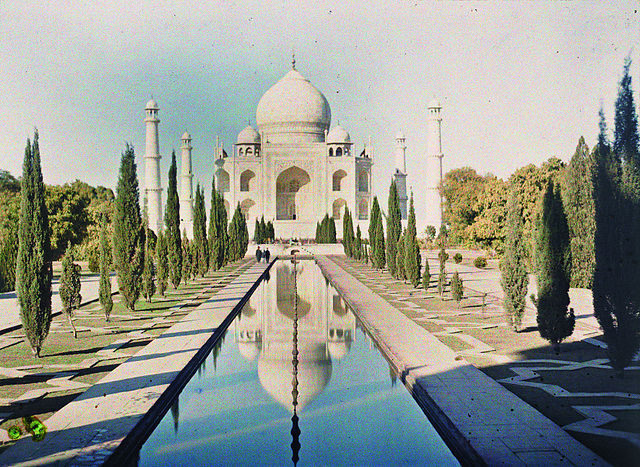

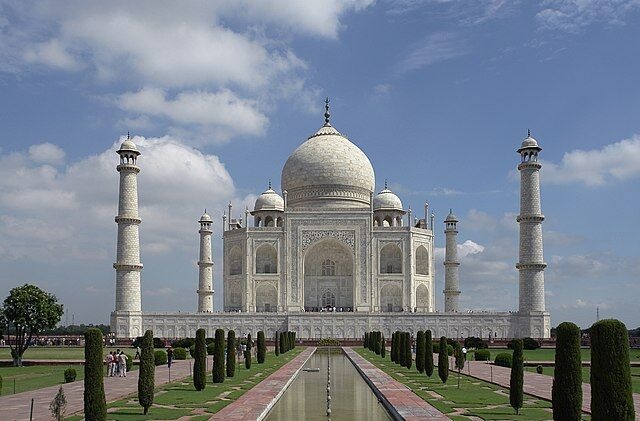

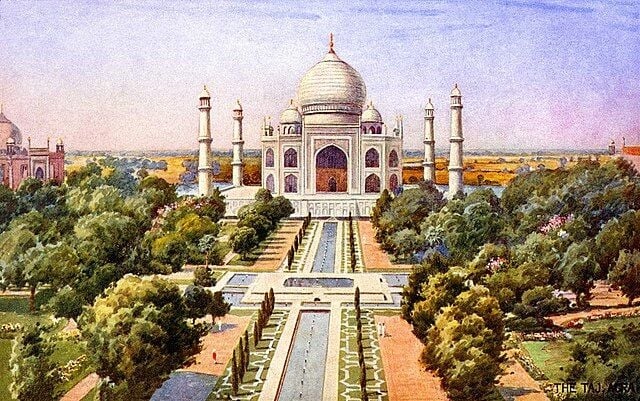

There is no doubt that the Taj Mahal deserves its ranking as one of the seven wonders of the world. Architecturally, it is stunning. And interestingly, the inspiration behind it is a very touching love story. In The Opposite of Indifference: A Collection of Commentaries, Aysha Taryam wrote, “The world believes it was built by love, but reading Shah Jahan’s own words on the Taj, one could say it was grief that built the Taj Mahal, and it was sorrow that saw it through sixteen years till completion.”

Shah Jahan, aka Prince Khurrum, built the Taj Mahal to house the tomb of his beloved third wife, Mumtaz Mahal. Although she held the third position in the household, Mahal was his soul mate, confidant, and the love of his life. But at what cost? Not many people know that the Taj Mahal cost 42 million rupees, on the backs of 22,000 slaves to build. And this money was collected by taxing local shopkeepers and workers, all the while banning others from building similar structures nearby. Join us as we explore a marriage that became one of the greatest love stories of all time.

A Shop Girl and a Prince

Born in Agra, India, in 1593, Mumtaz Mahal was a Princess born to Persian nobility. Even so, she worked as a shop girl, selling glass beads and silks in the Meena Bazar, which was attached to the Emperor’s harem. While this was an ideal location to meet the Emperor’s son, Shah Jahan, by chance, it was one y powerful woman that brought the two together.

Shah Jahan came from a long line of powerful ancestors. His mother’s side of the family were descendants of the Mongol ruler Genghis Khan, while his father’s family descended from Tamerlane, the Turkish barbarian. Oddly enough, the powerful person responsible for bringing these two together was related by blood to Mumtaz Mahal and only related by marriage to Shah Jahan.

The Puppet Master

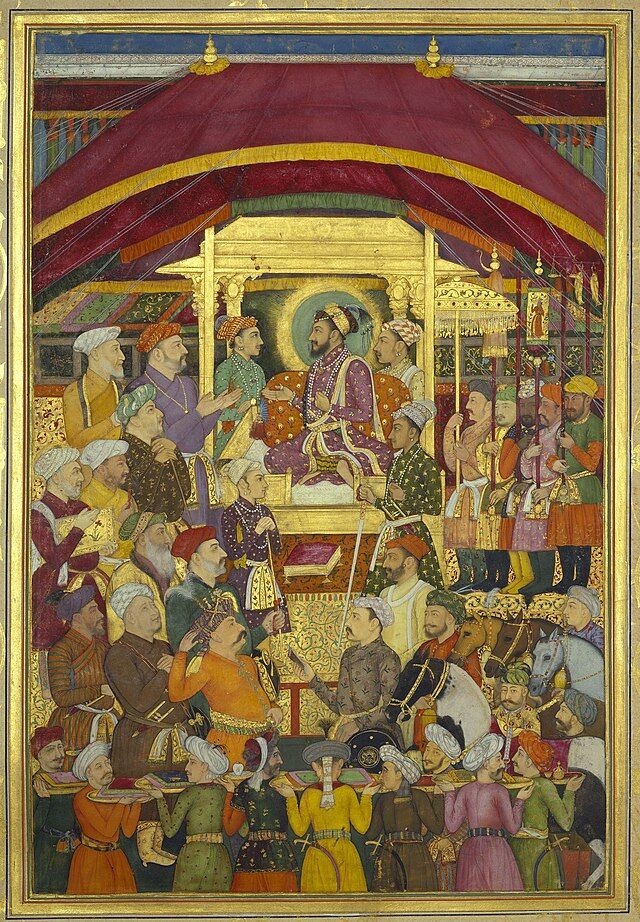

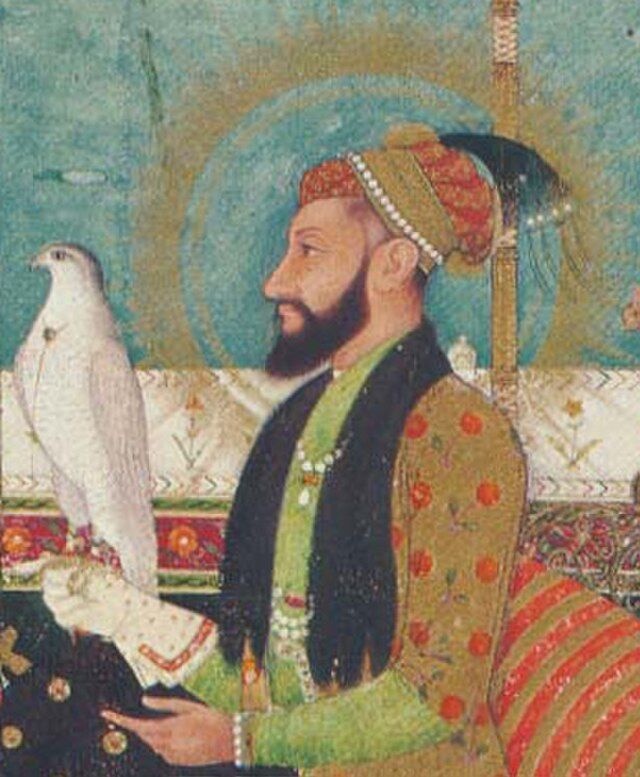

Nur Jahan was the aunt of Mumtaz Mahal and the stepmother of Shah Jahan. Although she was the 20th wife of the Emperor, Jahangir, she was his favorite and quickly became the true power behind the throne. Like a puppet master, Nur Jahan used her power and influence to convince the Emperor to grant her family members high ranking positions.

After arranging the marriage between her daughter from her first marriage to Jahangir’s fourth son, Nur Jahan offered her niece, Mumtaz Mahal, a position in the court. This wasn’t only done because of Mahal’s qualifications. Nur Jahan made this move intending to arrange her niece’s marriage to Shah Jahan.

Mahal Was a Catch

That’s not to say that Mumtaz Mahal wasn’t deserving of her position in the court. As a highly educated woman, she was fluent in Persian and Arabic, conversed using modesty and candor, and exuded talent and compassion. In other words, she was a complete package. It wasn’t hard for Nur Jahan to convince Jahangir to appoint her niece to a position in the court. By the time Mumtaz Mahal was an adolescent, she was already greatly admired by the nobles of the realm.

Once established in the court, Mumtaz Mahal proved herself worthy of great responsibility. And so, she was entrusted with the keeping of the royal seal of the land, the Mehr Uzaz, the highest honor the court could bestow. Her qualities not only helped her achieve this tremendous honor but also paved the way for her to become an Empress.

Love at First Sight

Nur Jahan’s meddling worked. With Mahal’s presence in the court, Shah Jahan quickly noticed her striking beauty and told his father it was love at first sight. The couple became betrothed when Mumtaz was 14, and Shah Jahan was 15, although they had to wait for outside sources to determine their wedding date. Choosing the marriage ceremony date was critical business within the realm. Court astrologers carefully reviewed their charts to select the time that would ensure a happy marriage.

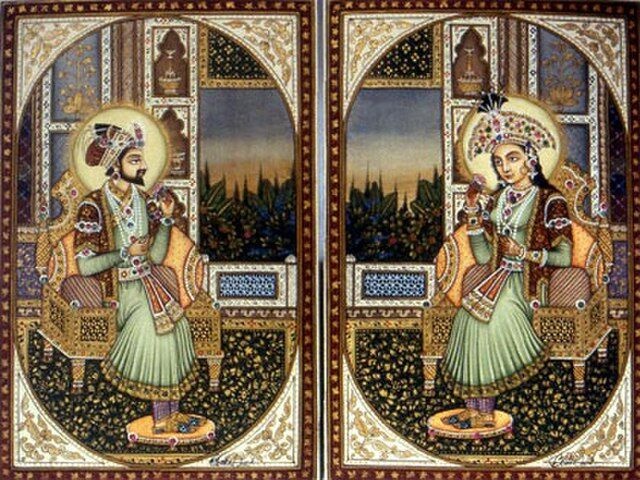

After careful calculation, the couple was wed on May 10, 1612, five years after their betrothal. Mumtaz Mahal was now the third wife of Shah Jahan. Despite her ranking, it didn’t take long for his third wife to become his favorite. Even though she was born Arjumand Banu Begum, Shah Jahan gave her the name Mumtaz Mahal meaning “Chosen one of the Palace” or “Jewel of the Palace.”

Stiff Competition

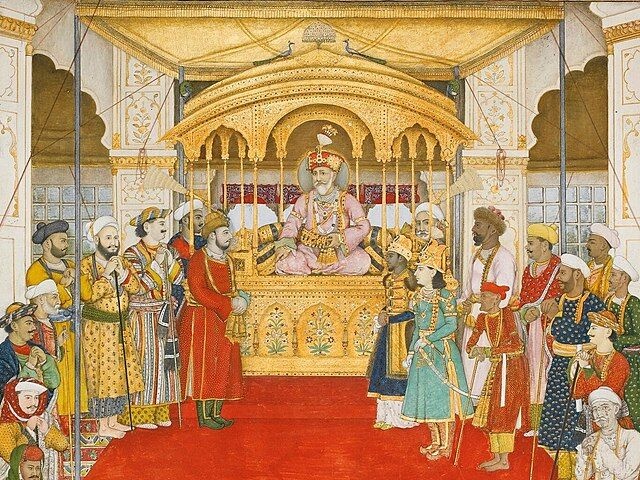

When Jahangir passed away, Shah Jahan was not automatically deemed his successor. In the Mughal Empire, being the firstborn held no clout regarding the throne. In addition to this ruling, the Emperor typically had multiple wives meaning numerous sons were vying for the position. Nur Jahan didn’t help matters either. Hoping to keep her control over the throne, she manipulated the court to put her son-in-law in power.

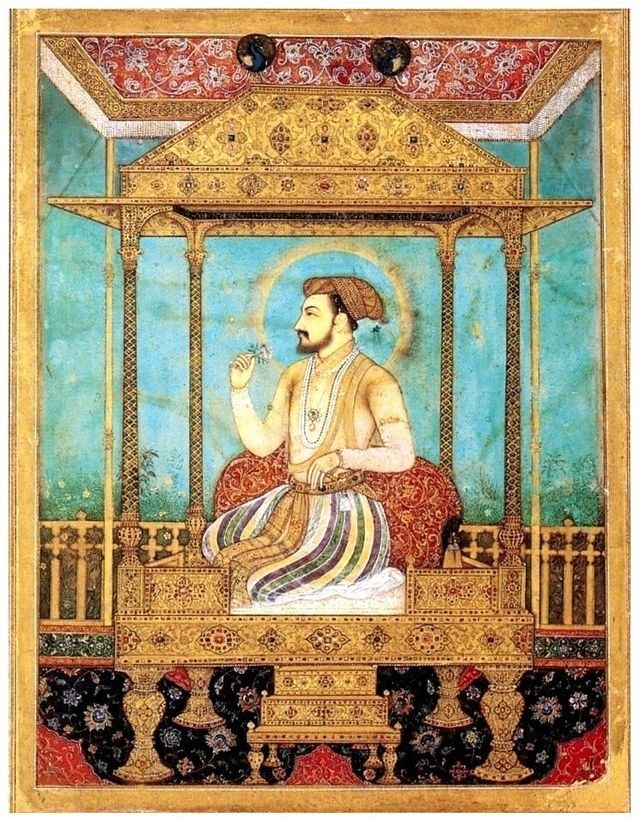

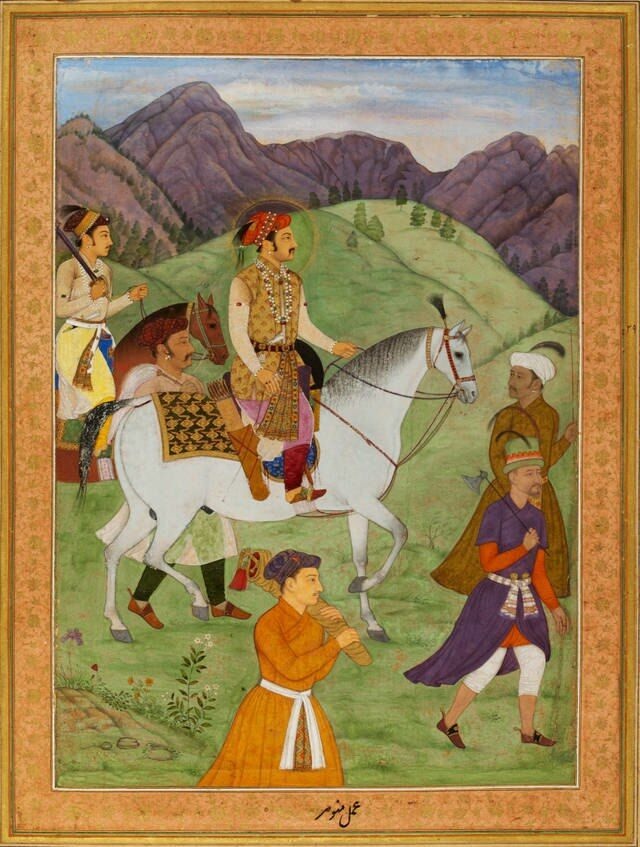

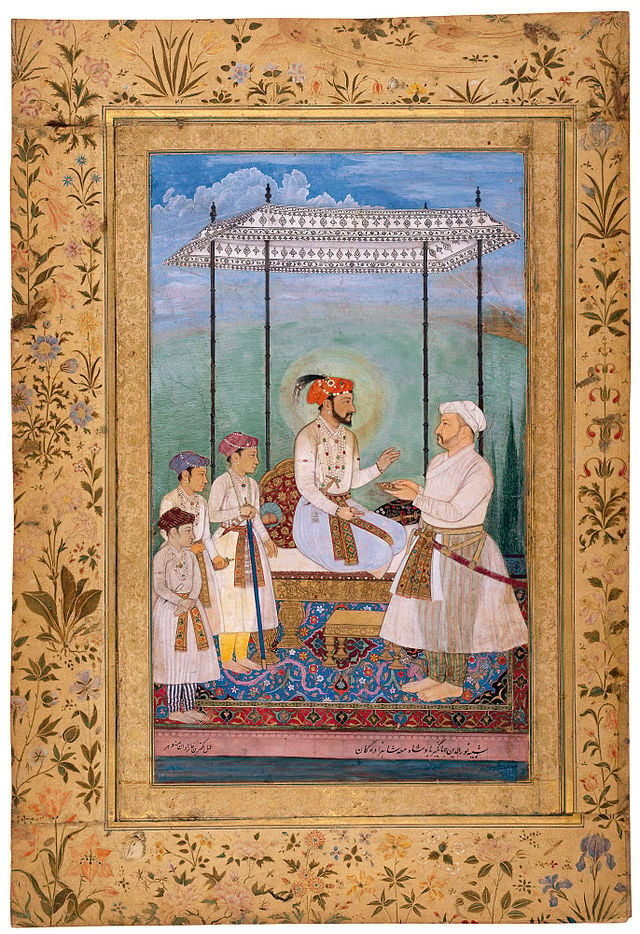

Shah Jahan did not sit idly by. Instead, he enlisted his Uncle to wage a revolt. Once they successfully subdued Shahryar Mirza, Shah Jahan ascended the throne. In his first order of business, he made Mumtaz his chief Empress with several titles, including Padshah Begum ‘(Lady Emperor),’ ‘Malika-i-Jahan’ (“Queen of the World”), ‘Malika-uz-Zamani’ (“Queen of the Age”) and ‘Malika-i-Hindustan (“Queen of the Hindustan”).

Refusing His Polygamous Rights

Shah Jahan wasn’t kidding when he said it was love at first sight. He rarely exercised his polygamous rights once he took Mumtaz Mahal as his third wife. He only had sexual relations with his first and second wives to sire a child with each. The Emperor’s historian, Inayat Khan, revealed, “His whole delight was centered on this illustrious lady [Mumtaz], to such an extent that he did not feel towards the others [i.e., his other wives] one-thousandth part of the affection that he did for her.”

Mumtaz Mahal had the same unwavering affection for her husband as well. As their love grew, the couple became inseparable. Even with Mahal’s numerous pregnancies, she traveled by her husband’s side as his constant companion, confidant, advisor, and lover.

A Tragic Death

As mentioned earlier, Mumtaz Mahal endured numerous pregnancies. In total, she gave birth to 14 children, although only seven of them survived. The labor and delivery of her 14th child, Princess Gauhara Begum, proved to be disastrous. The labor itself was so difficult that the couple’s 17-year-old daughter, Princess Jahanara, began gifting gems to the poor, hoping that the Gods would have mercy on her mother.

Tragically, there was no divine intervention. After 30 hours of labor, Mumtaz Mahal died of a postpartum hemorrhage on June 17, 1631, at the age of 37. Because she was accompanying her husband on a military campaign, her body was temporarily laid to rest in a walled pleasure garden in Burhanpur.

Her Dying Requests

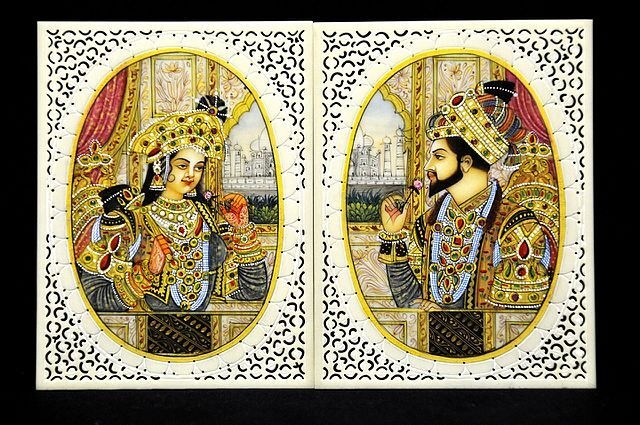

Even on her deathbed, Mumtaz Mahal was looking out for the best interest of her husband. In her final moments, she asked Shah Jahan to make her four promises. The first request was that he build a beautiful monument dedicated to their undying love. The second request was that he take another wife. For her third request, she asked that he be kind to their children. Lastly, for her final request, she asked that he visit her tomb every year on the anniversary of her death.

Shah Jahan delivered on the first promise as the Taj Mahal is a spectacular monument that captures his undying love for Mumtaz Mahal. As for her second promise request, her husband did take on two additional wives after Mumtaz’s death; however, he never again found a love like hers. And his children? Shah Jahan’s relationships with them became very complicated, as you will soon find out.

Their Daughter Stepped Up

As you can imagine, Shah Jahan was inconsolable after the untimely death of his beloved wife. Grief-stricken and in shock, the Emperor went into secluded mourning, only to emerge a year later with a full head of white hair, an aged face, and a bent back. The couple’s eldest daughter, Jahanara Begum, dedicated herself to aiding her father in his grief while also taking her mother’s place in the court.

Mumtaz Mahal left behind a personal fortune of nearly 10 million rupees. Half of her wealth was given to Jahanara, along with the responsibility of keeping the royal seal. The remainder of the fortune was divided between the rest of the children. This may seem like an unfair split, but Jahanara stepped into Mumtaz Mahal’s role as mother, member of the court, and her father’s caretaker.

Let the Planning Begin

As discussed, Mumtaz Mahal was temporarily buried in a pleasure garden called Zainbad, located in Burhanpur. Although it was a beautiful setting, Shah Jahan had something more spectacular in mind for her final resting place. Six months after her first burial, he had his wife’s body exhumed and returned to Agra, where her remains were interred in a small building along the Yamuna River.

When Shah Jahan went into his secluded mourning, he began planning his wife’s final resting place, what we now know as the Taj Mahal. He enlisted artisans from all over the Muslim world to add their talent to his creation. Although the planning began shortly after Mumtaz’s body was moved to Agra, the structure wasn’t finished until 22 years later.

Like Mother, Like Daughter

While Shah Jahan was obsessed with building the perfect tribute to his late wife, his eldest daughter, Jahanara, honored her mother by taking on her responsibilities. At just 17 years old, she was raising her brothers and sisters, helping her father through his grief, and restoring the court in order.

Ordinarily, this would be too much responsibility for such a young woman. But Jahanara was no ordinary young woman. Like her mother, she was well educated and became well respected for her knowledge of the Qur’an and Persian literature. In her spare time, she played hours of chess with her father, often outsmarting him with her maneuvers and winning the match. Jahanara was also fiercely independent and a true feminist, qualities rarely seen in women during that era.

Finding Her Spiritual Path

Despite her overwhelming responsibilities, Jahanara also dedicated herself to finding her spiritual path. Alongside her brother Dara Shikoh, she became a disciple of Mullah Shah Badakshi, who welcomed the two siblings into the Qadiriyya Sufi order in 1641. The Islamic belief known as Sufism encourages its followers to seek divine love and knowledge through their connection to God. Jahanara embraced the teachings of Mullah. Her dedication inspired Mullah Shah to make her his successor in the Qadiriyya; however, the laws of the order did not allow it.

This did not deter Jahanara from her spiritual path. Instead, she wrote two biographies, one of Moinuddin Chishti and one of her mentor Mullah Shah. Both of her literary works were highly regarded.

Divine Intervention

Three years after Jahanara’s initiation into Sufism, the Princess was severely burned when her clothes caught fire on her 30th birthday. Although the Empire enlisted every physician within the court to attend to her burns, no doctor was able to heal her. Then Jahanara met a beggar named Hanum, who was able to help. To her, this was a sign. Modern medicine wasn’t the answer; she had to follow her spiritual path.

Though Hanum had helped remedy her wounds, Jahanara was still suffering. So, she set out on a pilgrimage to Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti’s shrine in Ajmer. Within a year, she had healed completely. The Princess was so convinced that the pilgrimage and her faith had put a stop to her pain that she had a marble pavilion erected at the shrine and proceeded to write Chishti’s biography.

A Battle Between Brothers

Remember when we said that within the Mughal Empire, the throne was up for grabs should an Emperor become unable to rule? Well, that is exactly what happened in 1657 when Shah Jahan became gravely ill. Assuming their father would not recover, four of Shah Jahan’s sons went to battle over the right to the throne.

The Battle of Samugarh was fought between Shah Jahan’s eldest son, Dara Shikoh, and his third son Aurangzeb Bakhsh. These brothers had conflicting ideas as to how to rule the Empire. While Dara was a modern thinker, hoping for change, Aurangzeb was desperate to maintain his ancestors’ old, traditional values. Historians now believe that the conflict between these two brothers was a pivotal turning point in India’s history.

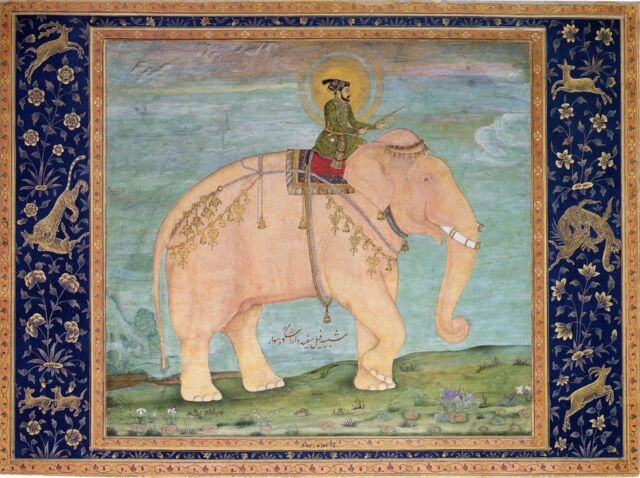

Behold the Elephant

And so, the brothers went to war. Though Dara was a more modern thinker, he wasn’t well versed in military strategy. After a back and forth of ferocious cannon fire that took out Dara’s key men, the young Prince decided to ride his elephant into battle, hoping the surge would convince Aurangzeb to retreat.

This was when he made a serious error. At the most crucial moment in the battle, Dara naively dismounted his trusted elephant. With the chaos and cannon fire surrounding them, the elephant followed his instincts and ran for safety instead of remaining by his owner’s side. When Dara’s troops saw their leader’s elephant running in the opposite direction, they assumed he had been killed and surrendered. This one misunderstanding changed the course of history in India.

A Tragic Betrayal

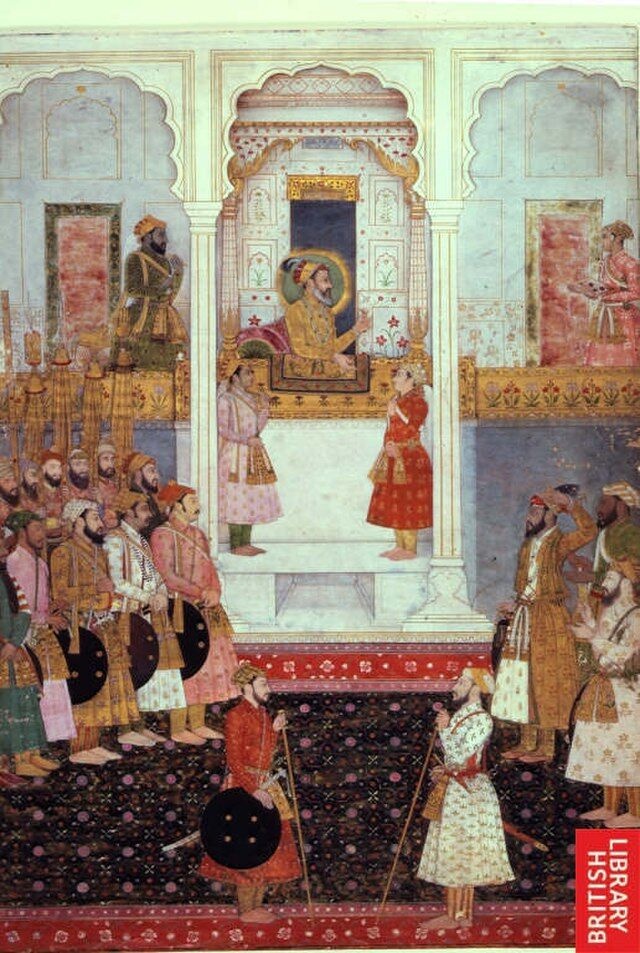

Aurangzeb declared victory over his brother Dara and immediately proclaimed himself Emperor. The problem was his father was still alive. Not only was Shah Jahan still breathing, but he had also made a full recovery and was ready to reclaim the throne. Drunk with power, Aurangzeb declared his father unfit to rule.

Fearing Shah Jahan would initiate a revolt, Aurangzeb had him shackled and sent to the citadel of Agra as a prisoner. As if that weren’t bad enough, he ordered his sister Jahanara to also be imprisoned so she could tend to her father as he rotted away in his cell. Shah Jahan spent the final eight years of his life in a stone chamber with only a small window that faced the Taj Mahal. He was never able to visit his wife’s tomb as she had requested.

A Divided Family

With Shah Jahan and Jahanara tucked safely away in the citadel prison, Aurangzeb ascended the throne with the help of Mumtaz Mahal’s second daughter Roshanara Begum. It was Roshanara who warned Aurangzeb of their brother and father’s plot to have him killed or imprisoned so he would no longer be a threat to the Empire. To reward his sister’s loyalty, Roshanara was given a prestigious position in the court.

Roshanara was taking a gamble by choosing Aurangzeb’s side. Had Dara been victorious, she would have most likely been imprisoned for treason. However, fate sided in her favor, and she soon became the most powerful woman in the Empire. Roshanara never regretted her decision but she lived in fear that Dara would seek revenge.

Masterminding an Execution

Roshanara’s fear regarding her brother Dara soon became paranoia. Whether it was her guilt or intuition, she knew the betrayal she caused by siding with Aurangzeb was reason enough for Dara to seek his revenge. Instead of attempting to reconcile with her brother, Roshanara came up with a more sinister solution.

Knowing that Aurangzeb was also concerned about a revolt, Roshanara approached her Emperor brother and suggested they execute Dara to alleviate the threat. Aurangzeb thought this was a swell idea. To kill two birds with one stone, Aurangzeb ordered Dara to be decapitated and then sent his severed head to the citadel prison as a gift to his father.

A Promiscuous Princess

Free from the dread of a hostile takeover, Roshanara felt empowered to behave in any way she deemed fit. You should know that in the Mughal Empire, Princesses did not date, nor did they take a lover. They were to remain single until a match was selected. Roshanara didn’t agree with these antiquated traditions. She had not one lover but many, much to the chagrin of her ultra-conservative brother, the Emperor.

In addition, Aurangzeb was fielding complaints from his wives regarding his sister’s management of his harem. Frustrated and embarrassed by Roshanara’s actions, the Emperor stripped her of her power and banished her to the garden palace in Delhi. His decision finally appeased his wives but left Aurangzeb without his number one advisor. As for Roshanara, she was pleased with his decision. She could now retire and have as many lovers as she desired.

Speculation Over Her Death

Unfortunately, Roshanara didn’t get to enjoy her retirement for long; by age 54, she died a gruesome death from poisoning. Now, here is where the speculation lies. Many historians believe that Aurangzeb had her discreetly poisoned after finding Roshanara with yet another lover in the palace in Delhi. Others have argued that the Princess and her lover most likely poisoned themselves in a suicide pact.

While it may seem like the first theory may be more likely, Aurangzeb was known for his devotion to his sister. He could have had her executed initially for disrespecting the laws of the Empire but chose to banish her instead. The Emperor also had his sister laid to rest in the Roshanara Bergh, a garden she commissioned and loved. If he was callous enough to murder her, why would he be so respectful of her remains? Sadly, the questions remain unanswered.

The Lust for Power

Aside from Jahanara, it would seem that the lust for power ran freely in all of Mumtaz Mahal’s children. Even though Aurangzeb, Dara, and Roshanara were the key players in taking over the throne, the second son, Shuja, also gave his brothers a run for the crown. Shuja was already the Governor of Bengal but he also prematurely tried to crown himself Emperor when Shah Jahan fell ill.

Both his older brother Dara and younger brother Aurangzeb agreed that Shuja’s lust for power and ill attempts to reign supreme had to be stopped. Of course, it was Aurangzeb who took action. Instead of heeding off an attack by Shuja, Aurangzeb sent his captain Mir Jumla as the aggressor. Overpowered, Shuja retreated to Bengal.

Never Give Up

That wasn’t the end for Shuja; as far as he was concerned, where there is a will, there is a way. He had been defeated by both of his brothers on previous attempts to overtake the throne but he tried one more time in 1659. By then, Aurangzeb was the self-proclaimed Emperor, and Dara was dead.

In a bold move, Shuja marched into the capital and initiated the Battle of Khajwa on January 5. Unbeknownst to Shuja, his army began deserting, leaving him to fight an unfair battle against his brother. Once again, he was defeated and fled to Bengal. Shuja’s lust for power was strong. Even after being defeated by two of his brothers on multiple occasions, he reorganized his army for another coup attempt. After losing yet another battle in 1660, the second son finally gave up.

Broken Promises

We mustn’t forget the youngest son of Mumtaz Mahal and Shah Jahan, as his story could be straight out of Game of Thrones. Murad Bakhsh also felt he should be entitled to his father’s throne when Shah Jahan fell ill. However, what should be noted about the youngest son is that he was a bit too trusting and, therefore, naive.

Like Roshanara, Murad aligned himself with Aurangzeb when he went to battle against Dara. Why? Well, his older brother made him a promise that the kingdom would be split once they reigned victorious in the war of succession. Of course, Aurangzeb had no intention of sharing the crown; this false promise was just a way to enlist his brother’s help. After Murad led the charge to defeat Dara in the Battle of Samugarh, Aurangzeb got him drunk and had him imprisoned before sentencing him to death in 1661.

The Death of Shah Jahan

After spending eight years in prison, Shah Jahan fell gravely ill in January 1666. He passed away on January 30th after reciting verses from the Qur’an at the age of 74. His daughter Jahanara planned a glorious funeral for her father, complete with a procession of nobles carrying his body and gold coins for the less fortunate.

Aurangzeb refused to honor his father with such ostentation. Instead, he placed his remains in a sandalwood coffin and had him interred next to his mother in the Taj Mahal. While this may seem like a loving gesture, we assure you it wasn’t. First of all, the Taj Mahal was not designed to house two tombs, so the aesthetic was lopsided with the addition of Jahan’s casket. Secondly, Aurangzeb refused to erect a separate monument for his father, opting for the easier solution of using the Taj Mahal.

Insulting His Father’s Creation

Shah Jahan designed the Taj Mahal to be perfectly symmetrical for a reason. During his years of planning, he consulted numerous experts to ensure that his beloved wife’s remains would always be protected. As an example of his forethought, the four spires in each corner of the spectacular structure were designed to lean outwards. Should a natural disaster occur, causing the structure to become unstable, the spires would fall away from Mumtaz Mahal’s tomb.

Shah Jahan had his beloved wife’s tomb placed in the exact center of the crypt to ensure the safety of her remains and to create a perfectly beautiful and symmetrical monument in her honor. So, when Aurangzeb disrespectfully had Shah Jahan interred there, he purposely insulted his father’s creation.

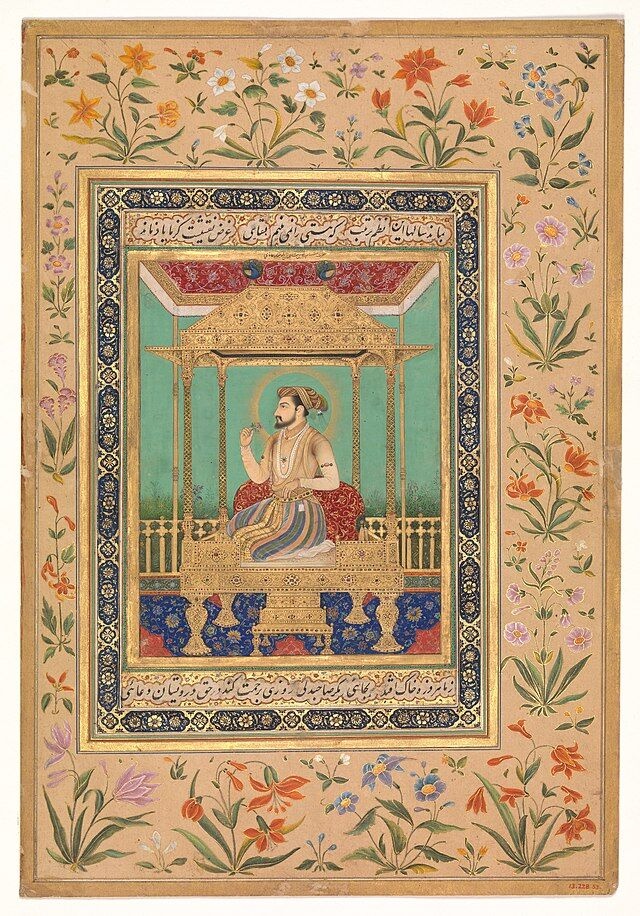

Proud as a Peacock

Even though the Taj Mahal was Shah Jahan’s labor of love, the Emperor also had a passion for design and building. Yes, the Taj Mahal is the most famous of his creations and took the longest to construct, but it wasn’t the most elaborate of his projects. The winner here goes to Shah Jahan’s Peacock Throne, one of the most magnificent and indulgent royal thrones in existence.

Imagine this. Steps of silver leading up to solid gold feet embossed with rare gems. At the back of the throne are two fans of peacock tails delicately lined with rubies, diamonds, sapphires, emeralds, and other rare gemstones, completing the colors of a rainbow. With the amount of detail and the precious stones and metals, the Peacock Throne cost twice as much to build as the Taj Mahal.

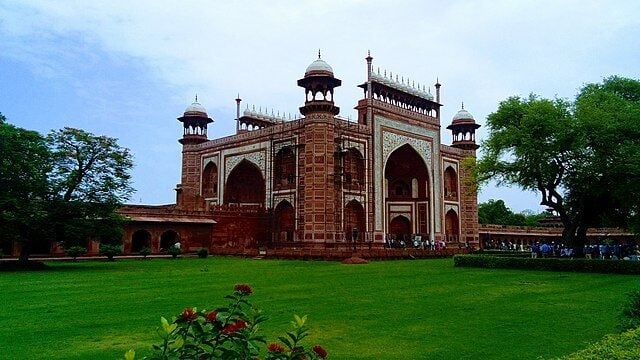

A Residence Fit for an Emperor

Before constructing the Taj Mahal and the Peacock Throne, Shah Jahan built the Red Fort Complex that included his private residence, the Khan Mahal. Like the Taj Mahal, the complex and home were completely symmetrical and architecturally astounding. The construction was commissioned in 1638 and was finally completed in 1648 for the cost of 50,000 rupees.

While there were many exquisite pieces of art inside the residence, one important piece from the Mughal Empire was built into the northern end of the sitting room. Here lies a beautiful marble screen carved with a Scale of Justice suspended over a crescent surrounded by clouds and stars. Was this a testament to Shah Jahan’s leadership style? Perhaps, but it also shows his attention to detail and love for beautiful things.

History Repeated Itself

Aurangzeb ruled India for a whopping 49 years. A true traditionalist, he wiped out any practice of Hinduism in the region and instead spread the rule of Islam. Sadly, this was not the intention of the Mughal rulers that preceded him; their goal was to unify and integrate rather than persecute.

Like his father, Aurangzeb never declared an heir, so when he passed, yet another war of succession occurred between his three sons. The eldest, Azam Shah, felt entitled to the throne, so he went to battle with his younger brother Bahadur Shah. This wasn’t the brightest decision as Bahadur had experienced trying to overthrow a ruler before. He attempted to conquer his father on several occasions. The youngest, Kam Bakhsh, had established his empire in Bijapur, so once Azam was defeated, Bahadur became emperor.

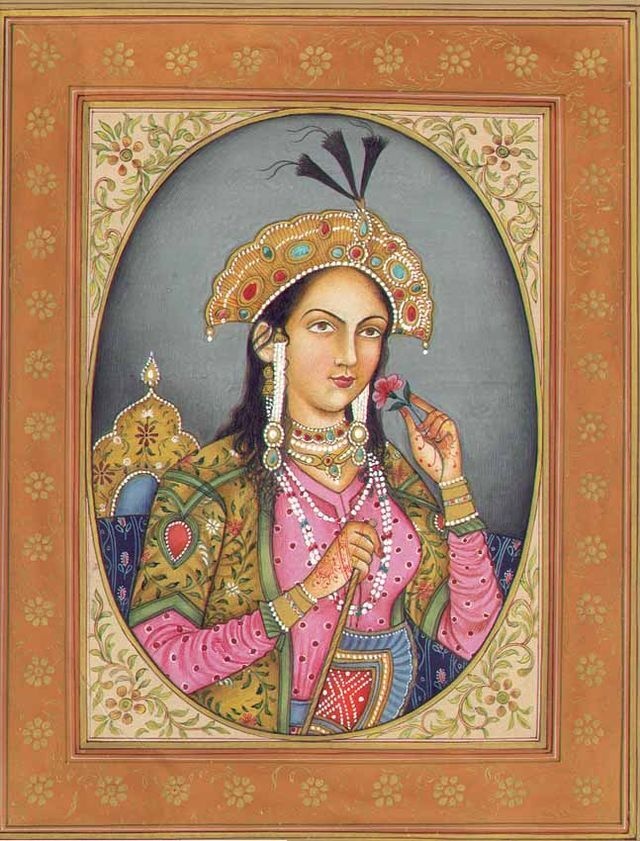

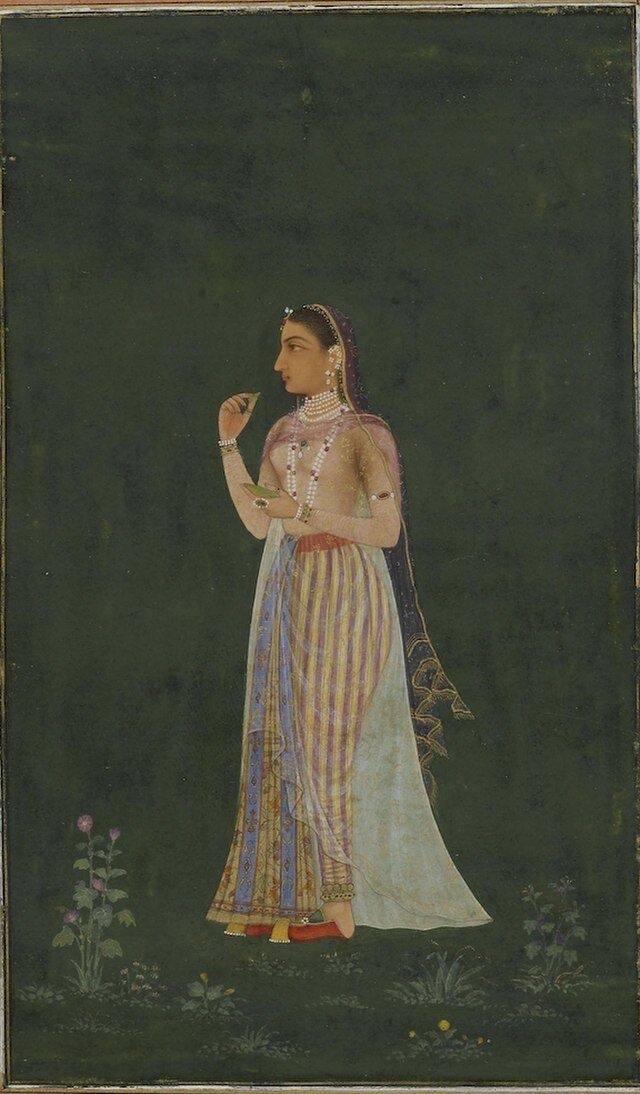

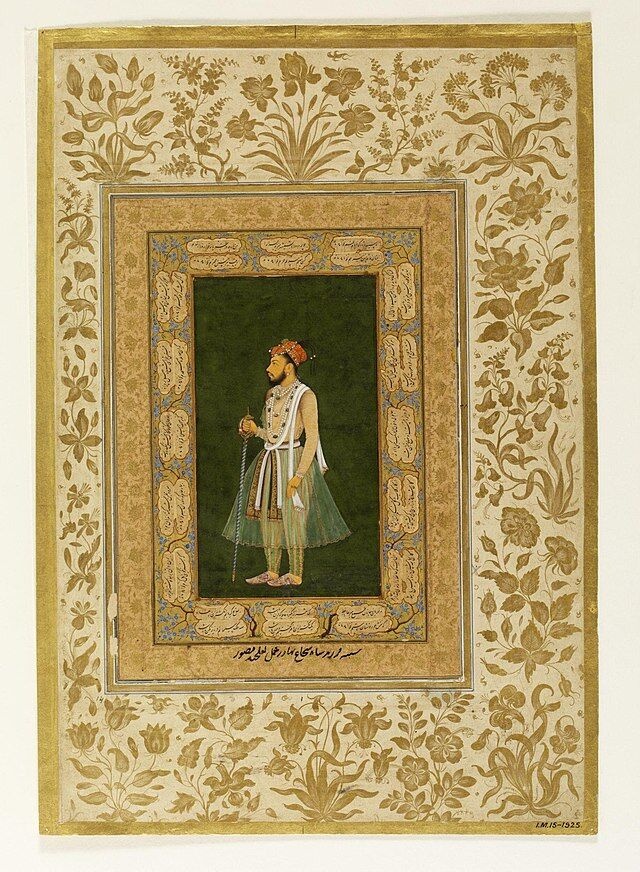

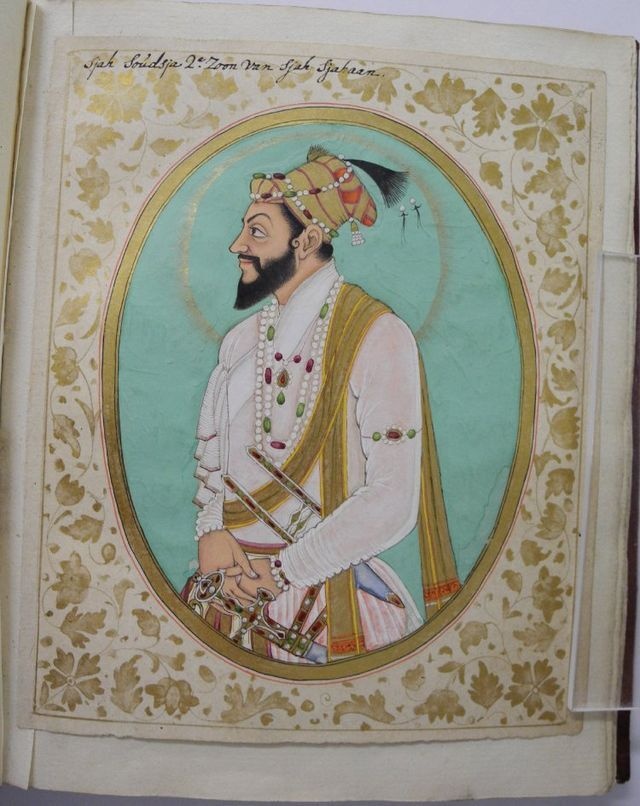

Forever Hidden

As for Mumtaz Mahal, she was deeply respected and loved for her compassion, intelligence, and loyalty, all things lacking in most of her children. Despite her impact on India and Shah Jahan, there are no paintings of her in existence. Because of the Muslim “Law of the Veil,” women must keep their faces covered while in public, including those considered royalties. Even sitting for an artist would be regarded as showing one’s face in public, so no paintings were ever created. All of the paintings of Mumtaz were created post-mortem.

To further enforce their belief that vanity is a dishonorable attribute, tombs cannot be elaborately decorated. Although her crypt is one of the most ornate architectural structures in the world, Mumtaz Mahal’s grave remains relatively plain out of respect for Muslim beliefs.

Now that you have learned about the love story that gave birth to the Taj Mahal and about the Indian empire, let’s switch timelines so that you can delve into the life of one of the most famous emperors of Ancient Rome. Up next, Augustus: The First and Greatest Emperor of Ancient Rome.

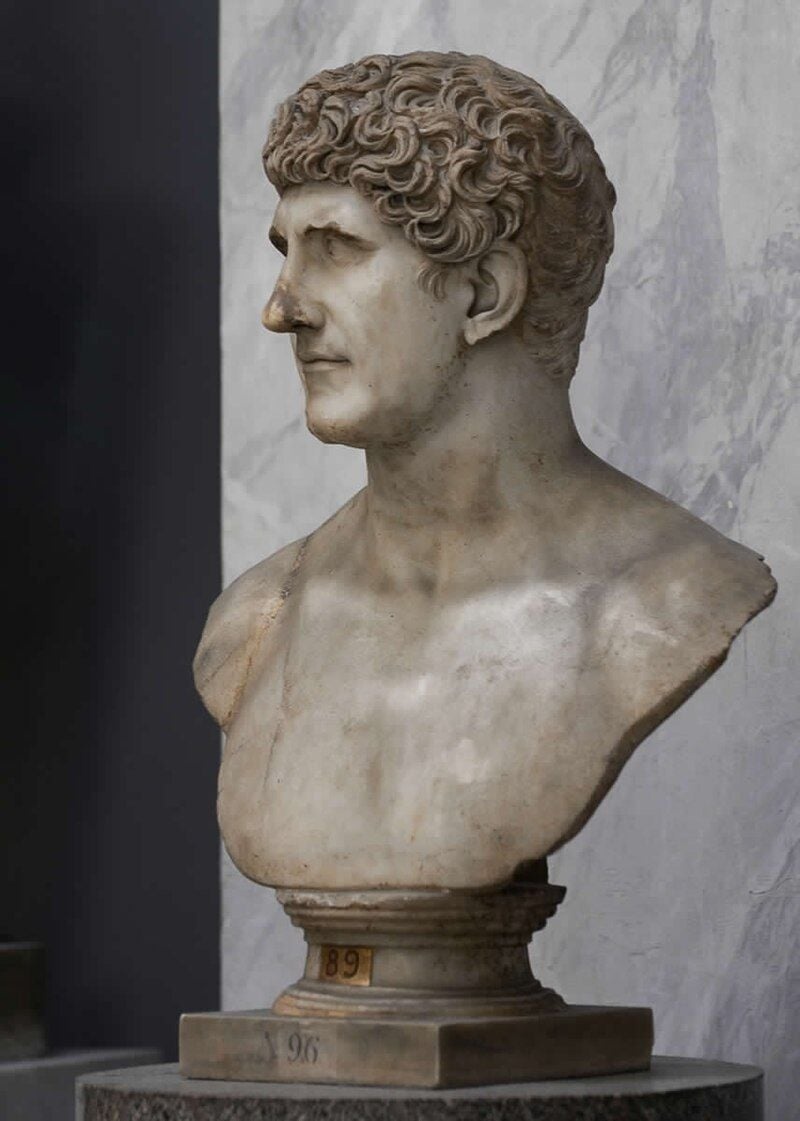

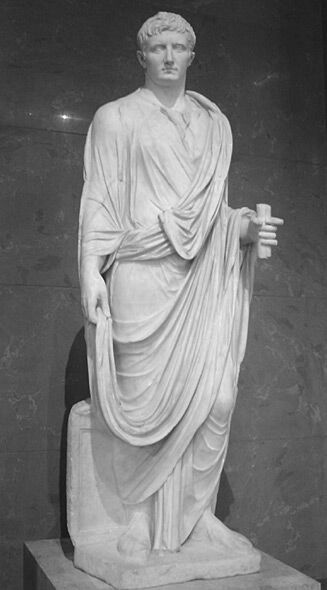

Augustus: The First and Greatest Emperor of Rome

Augustus was a man of many contradictions. Powerful enough to topple his enemies and command armies, yet constantly dogged by illness throughout his life. Appointed by Julius Caesar as his successor, he accomplished more than anyone else in his family line had in terms of their goals for Rome.

Under his rule, the Roman Republic became an empire. He was loathed as much as he was revered by those he ruled. This is the story of the first Roman emperor.

What’s in a Name?

On 23 September in 63 BCE, a boy child was born. The name given to him was Gaius Octavius Thurinus, although he would adopt different names throughout his lifetime and thereafter. Historians refer to him as Octavian for part of his life between being adopted by Julius Caesar and stepping into his new identity as Augustus. The Bard, William Shakespeare is partially responsible for this Anglofication in his play, Julius Caesar, which inspired historians to adopt this shorter moniker.

His family name, “Thurinus”, is derived from a victory his father had in a city called Thurii when slaves amassed a rebellion. Octavius was born in Rome, but the city was swarming with people, and such a place wasn’t suitable to raise a future leader. So he spent his childhood at the peaceful family estate in Velletri.

He Held Power for a Long Time

Since he fought hard to be the first Roman emperor, Augustus wasn’t about to give up his reign. He succeeded where even the great Julius Caesar had not, and he was young enough to carry out his visions to fruition. He oversaw Rome as their ruler for 41 years.

Antonius Pius held the second-longest rule over Rome over a hundred years after Augustus’ death, and the span of his rule fell short of 23 years. This means that Emperor Augustus held power for 18 years longer than any subsequent ruler.

A Young Boy and an Old Woman

Octavius’s father died when he was still a young boy and his mother remarried not long thereafter. As a result, Octavius was left to the care of his grandmother, Julia, who was the sister of Julius Caesar. She passed away around 51-52 BCE when he was about 10 years old.

He personally delivered the formal speech of mourning at her funeral. After her death, his mother and stepfather became more involved in his life and raising him. He started wearing the Toga Virlis four years later, which was symbolic of becoming a man.

Having Family in High Places Helps

In 47 BCE, at the age of 15, Octavius was elected to the College of Pontiffs. This was a significant honor in these times. Before Christianity became the dominant religion practiced in Rome, it was the duty of the priests of the College of Pontiffs to advise the Roman Senate on matters pertaining to the gods.

The honor of becoming a member was usually reserved for those who were very wealthy or politically connected. In fact, it was Julius Caesar who nominated Octavius for the position, as the ancient Romans were big fans of nepotism.

The Struggles He Endured to Reach Caesar

Octavius was eager to join Caesar’s civil war as it raged in Africa, but his mother had concerns and after much protesting, he conceded to wait. She eventually agreed that he ought to go and join the battle in Hispania, where Caesar was doing battle with Pompey’s forces, but then he was struck by sickness so severe that it rendered him unable to travel.

Once recovered, he took to the seas with urgency but he was shipwrecked on his journey to Ceasar. He and a few brave men fought their way through hostile territory to reach Caesar’s camp. His efforts so impressed his great-uncle that upon his arrival back in Rome he had his will amended to name Octavius as the main beneficiary.

Training to Be the Next Big Thing

Since Octavius was to be named as Caesar’s heir, he would require the appropriate education and military training. For this, he was sent to Apollonia in Illyria. Caesar never stopped plotting the next move, and for his next campaign, he was planning to invade the Parthian Empire in 44 BCE.

Caesar had given Octavius the title of “Master of the Horse” and as such, he would act as his lieutenant. Six legions had been sent to Macedonia for training and Octavius was their point of contact while at Apollonia. Caesar was assassinated three days before the campaign was due to start. Octavius was only 19.

Slipping Into New Names and Titles

When Octavius received word that Caesar had been assassinated in 44 BCE, he had still been at Apollonia. Instead of opting for the safety of Macedonia with the troops, he made his way to Italy, where he discovered that Caesar’s will had named him his heir.

He elected to take the name of his great-uncle, Gaius Julius Ceasar, to establish and reinforce his claim, as Caesar had no children and some would doubt the legitimacy of Octavian’s claim to power. There is no evidence that he used the name Octavianus, so to avoid confusion between him and his predecessor, historians refer to him as Octavian during this period.

Stepping on the Wrong Toes Has Consequences

After learning of Caesar’s will, Octavian made his way to Rome. Mark Antony had been appointed as the consul on Caesar’s death. He had tentatively made a truce with some of those responsible for having their former ruler murdered while driving others out of the city.

Antony wanted to maintain his position of power and wouldn’t relinquish Octavian’s inheritance, as he’d hoped he would be named Caesar’s political heir. However, Octavian had amassed more support and forces, with some of Antony’s own forces electing to join Octavian’s army. Antony was forced to flee and was declared an enemy of the state.

The Enemy of My Enemy Is My Friend

When Antony fled Rome, he went to the province that the senate had promised to him, which was formerly assigned to one of Caesar’s killers – Decimus Brutus. Brutus refused to relinquish his lands to Antony. The Senate decreed that there should be no fighting, but they had no army to enforce this.

Fortunately, Octavian had forces aplenty and he did their bidding, defeating Antony’s forces and forcing him to flee once again. But the senate gave more praise and accolades to his great-uncle’s assassin than to him, and Octavian didn’t take kindly to it, and it led to his taking action against the Senate and Brutus.

A Bizarre Twist of Fate

The Second Triumvirate was formed in 43 BCE and was comprised of Octavian, Antony, and Marcus Lepidus. The latter had also been a close ally of Caesar’s and was who Antony had formed an alliance with after his most recent defeat. It seems that alliances were formed with the change of the wind in these times.

The circumstances that brought the Second Triumvirate into being were not ordinary and required putting pride and past grievances aside in order to achieve what none could have done on their own. Three bloodthirsty and ambitious men with power got together and plotted revenge and conquest. They started with the accrual of funds.

They Got Blood on Their Hands

The Second Triumvirate ordered proscriptions of masses of people who had enjoyed affluent, comfortable lives. Between 130 and 300 senators, and up to 2,000 citizens who owned property were branded as outlaws and stripped of their rights and assets. Those who didn’t flee were murdered. The triumvirs offered rewards for any proscribed individuals that were arrested.

It is said that the proscriptions were a way of eliminating political enemies for all three triumvirs and amassing funds to pay troops in the upcoming battles against those responsible for murdering Caesar. The triumvirs all threw certain friends and family under the bus for proscription.

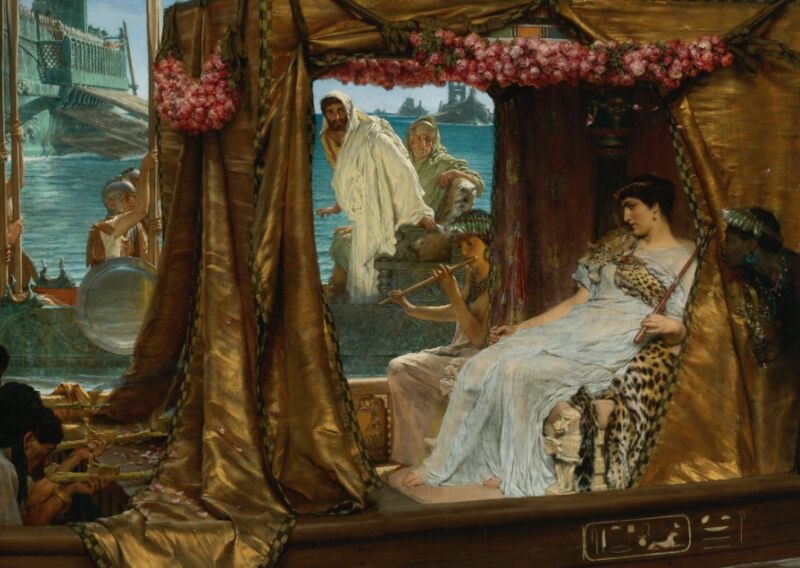

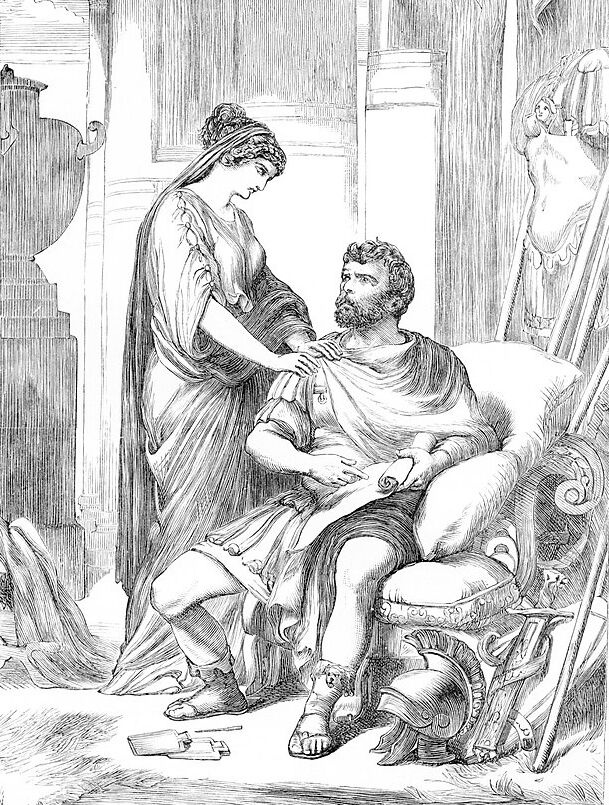

Alliances Through Marriage Are Risky Affairs

Octavian and Antony realized that it was in both of their best interests to put their vendetta aside. They would both achieve much more if they pooled their influence, experience, and resources. But how could either one trust the other not to stab him in the back at the first given opportunity?

The answer, of course, was through marriage. Augustus married the daughter of Antony’s first wife, Claudia, while Antony married Octavian’s sister, Octavia. Things didn’t work out. Two years later, Augustus returned Claudia to her mother, claiming that the marriage was never consummated. Antony, on the other hand, fell in love with Cleopatra. They had twins together and lived in Egypt.

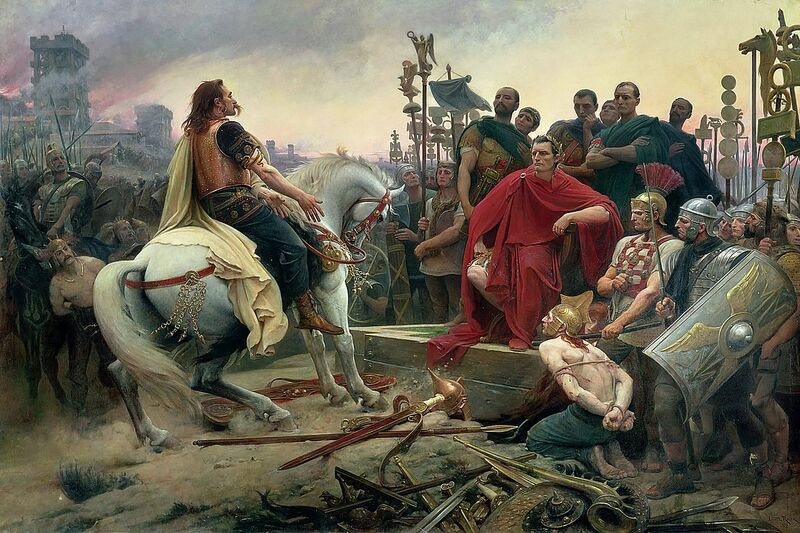

The Battle of Philippi Involved Many Lives

The battles that took place at Philippi in Macedonia in 42 BCE were some of the largest Roman civil wars in history and they were the final wars of the Second Triumvirate. They both happened within the month of October and were fought between the forces of Octavian and Antony versus those of Brutus and Cassius.

The battles lacked any strategy or discipline, counting instead on sheer numbers to clash at each other in an amateur fashion. Of the 200,000 involved in the clashes, close to 25,000 died. The suicides of Brutus and Cassius put an end to the violence, even though the opposing forces had sustained more losses.

More Fuel to the Fire for Antony

Augustus may have brought his numbers and his reputation to the battles of Philippi, but how much involvement he had personally is up for debate. Reports say that Augustus had suffered illness throughout the campaign that left him unable to lead his troops.

He had to hand over military command to Marcus Agrippa in his place. During the initial battle, Brutus’ forces pushed Octavian’s all the way back and entered their camp. Both battles were won as a result of Antony’s command and the action of his forces.

Division of Spoils Was Far From Equal

Octavian and Antony sent forces after Brutus and Cassius – who were primarily responsible for the assassination of Caesar. They fought in Macedonia and the battle concluded when Brutus and Cassius both committed suicide.

After the battle, territories were divided among the triumvirs based on their spheres of influence. Antony got the east, the province of Gaul. Octavian took the lands of the west, including Spain, which had belonged to Lepidus. Lepidus was left with the province of Africa, which was essentially the unwanted dregs.

Caught Between a Rock and a Hard Place

Once the battle had been fought and won, Octavian was left to solve the issue of where to put all the soldiers. There were tens of thousands of soldiers who had fought on either side of the battle who now needed to be settled.

If he didn’t honor the promises the triumvirate had made to grant the soldiers land, he risked having them join his opposition. There weren’t any easy solutions to the problem, so he chose the one that would cause the least damage to himself. He confiscated land belonging to Roman citizens and redistributed it to the soldiers.

Lepidus Got the Short End of the Stick

The Second Triumvirate initially awarded the lands of Sicily to Sextus Pompeius, who was the son of Caesar’s great rival Pompey. But over time, the relationship between the parties became more tenuous and rocky, eventually resulting in conflict. Lepidus amassed a considerable force against Pompeius.

Feeling slighted at the prior distribution of territories, Lepidus attempted to claim Sicily for himself. Octavian turned this ambition around on him and accused Lepidus of rebellion. Lepidus’ forces defected to Octavian at the lure of money. Lepidus was left with no choice but to submit to Octavian.

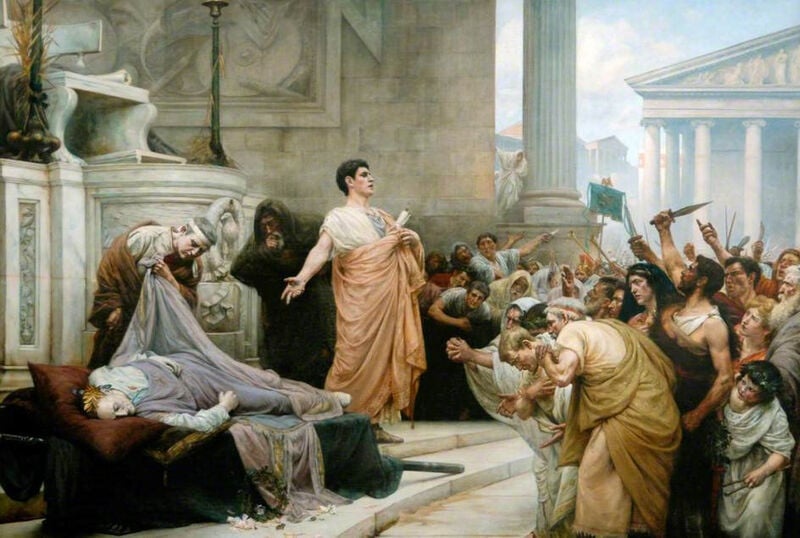

And Then There Was One

Octavian couldn’t rest until all the potential threats to his position of power had been eliminated. This means he would have to go after Antony and his lover, Cleopatra. Octavian set to work tarnishing Antony’s reputation and turning the Roman people against him. He obtained Antony’s will by force and made it public, using private information contained therein as grounds to wage war upon the lovers.

In 30 BCE, Anthony and Cleopatra were defeated at the battle of Actium and committed suicide rather than be captured by enemy forces. With their demise, there was no one left in Octavian’s way in his pursuit of taking the power of Rome.

He Played It Cool to Get Ahead

Augustus realized that he would have to play a long slow game of grasping power if he was to avoid the same fate that had befallen Julius Caesar and Mark Antony. Rome didn’t want another dictator, and being overzealous would be to his detriment. He decided to play it coy.

While he commanded the loyalty of all the armed forces, he pretended to cede all governing power to the Senate. But the nation was in chaos and without armies to maintain order, society would devolve into ruin. Eventually, the Senate kept control of six legions and gave 20 to Augustus, along with the territory which they kept in check.

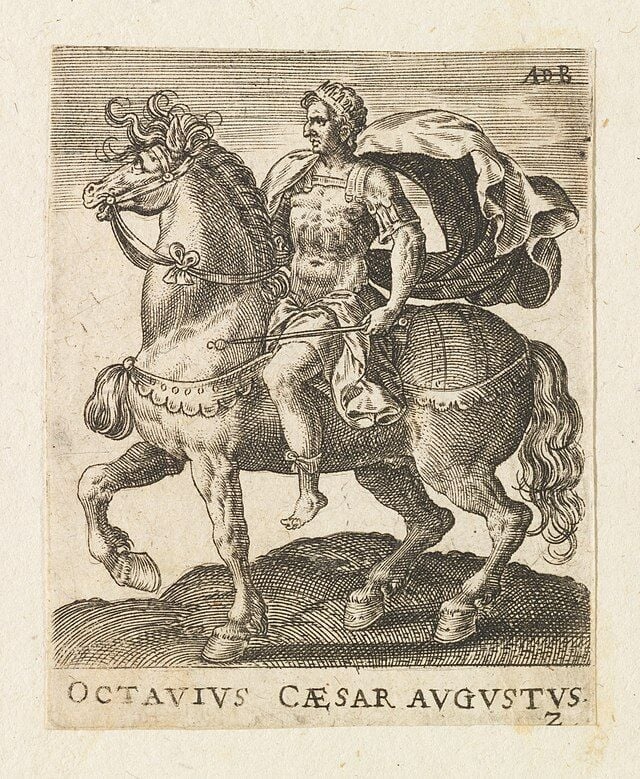

The Next and Final Name Change

The name “Augustus” is rooted in the Latin word Augere – meaning to increase. In this contact, Augustus can be translated as “the illustrious one.” The Senate gave him this name after he defeated Antony and Cleopatra. Since it was a name given to him because of his achievements and not passed down from the achievements of family members, it was a great honor. He was able to start a new family name to pass on.

He wore it with pride and kept using it for the remainder of his life. In fact, the seventh and eighth months of the year are named July and August, after Julius Caesar and Augustus, respectively. On the Roman calendar, August was the sixth month of the year and was called Sextilis.

Playing the Part of a Humble Man

Octavian understood the power of aesthetics and the message they sent to the world. He elected to make himself appear to shirk off the trimmings associated with power and the ruling class, unlike his great-uncle Julius Caesar. He renounced all the insignia of power. In fact, some sources say he didn’t put much stock into appearing groomed at all.

His teeth weren’t well maintained and his hair wasn’t in the style of the times. Perhaps he was going for a more rugged look. One aspect of his appearance he may have altered was his height. At 5.7”, he wasn’t very imposing. Some Roman historians say he had shoes that helped to amend this.

He Had That Gleam in His Eye

Augustus was better at conquering nations than he was at finding love. In his lifetime, he pledged himself to three different women, and he wasn’t happy in any of these relationships for long. The third marriage lasted a long time, as opposed to the first two, which both lasted two years before concluding in divorce.

It is speculated that Augustus may have been poisoned by Livia Drusilla, the last woman he married. Her son was Tiberius, and to assist her child in obtaining power sooner, she helped nature along in getting Augustus into the grave.

Turning a Loss Into a Win

Augustus achieved many notable victories during his time as emperor, but one of the contributions he is most praised for stems from defeat. At the Battle of Carrhae, the Parthian forces obliterated the Roman forces. In 20 BCE, 33 years after the battle, Augustus negotiated the return of the battle standards Rome had lost that day.

Even though many Romans felt that there should have been a retaliation, Augustus turned the outcome of the negotiations into a show that the Parthians had submitted to his will, and hence gave a great boost to the morale of the troops. He avoided further conflict with a powerful enemy and made his people feel like they were victorious.

He Had but One Daughter

Octavian had one biological child in his lifetime, a daughter with his second wife. They named her Julia. He was very fond of her when she was a child and by all accounts, she was a lovely person. Unfortunately, the role of women in ancient Roman times was not such that Octavian could pass the keys to the kingdom on to his daughter. He needed a son to carry on his name and keep power in the family.

In 25 BCE, Augustus arranged for Julia to marry Marcellus, his nephew. But illness took him within a few years. This time Octavian wed her to his friend and general, Marcus Agrippa. The fact that he was 22 years her senior didn’t prevent them from having three sons and two daughters together. Two of her sons died before reaching adulthood and the other was exiled.

He Wasn’t Finished Playing Matchmaker

With such a big age difference between Julia and Agrippa, it should come as no surprise that he died before she did. So of course, Augustus stepped in yet again and arranged a husband for her. This time, he looked even closer to home than before.

He made her marry Tiberius, his third wife’s son. Tiberius had been happily married to another woman, and Augustus insisted he divorce her in order to marry Julia. Julia and Tiberius disliked one another.

She Was No Longer Daddy’s Little Girl

She may not have been able to refuse the marriage that Augustus arranged for his own political gain, but there was no love between Julia and Tiberius, and she didn’t feel she owed him any loyalty. She went looking for love in other places. While her husband was gone, she was charged with adultery.

Her father offered her lovers the option of exile or suicide, while Julia was charged with treason. He arranged her divorce and banished her to an island named Pandateria. She lived out her life there, not permitted to partake of wine or receive visitors that didn’t get his prior approval.

He Was Great at Organizing Forces

The first designated police and firefighting squads were brought together under the authority of Emperor Augustus. Since forces no longer needed to be engaged in battle when the civil wars had come to an end, he also created a standing army numbering 170,000 strong.

He also established the Praetorian Guard. They were originally developed to provide personal protection to the emperor while in battle, but their duties and power evolved. They served as the imperial guard and held the power to intimidate the senate and remove emperors that weren’t living up to their standards, as in the case of Caligula. They even instated his replacement.

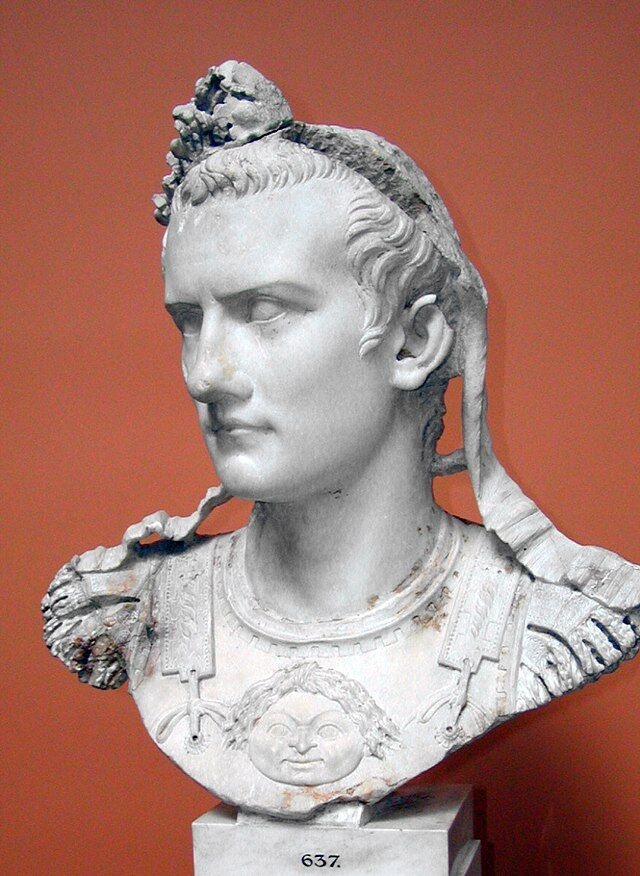

The Story of the Mad Emperor

Emperor Caligula, the grandson of Augustus, wasn’t remembered fondly in history. Some accounts speak to his cruelty and sexual perversion and through his acts as emperor, we gather that he was most interested in making a life of luxury for himself. He was also said to be quite mad.

An example of a failing in reasoning on his part was to perpetuate the notion that he was the product of incest. He claimed that his mother was the child of Augustus and his daughter Julia. He felt more comfortable with that narrative than to concede that his mother, Agrippina, was the child of the soldier Agrippa.

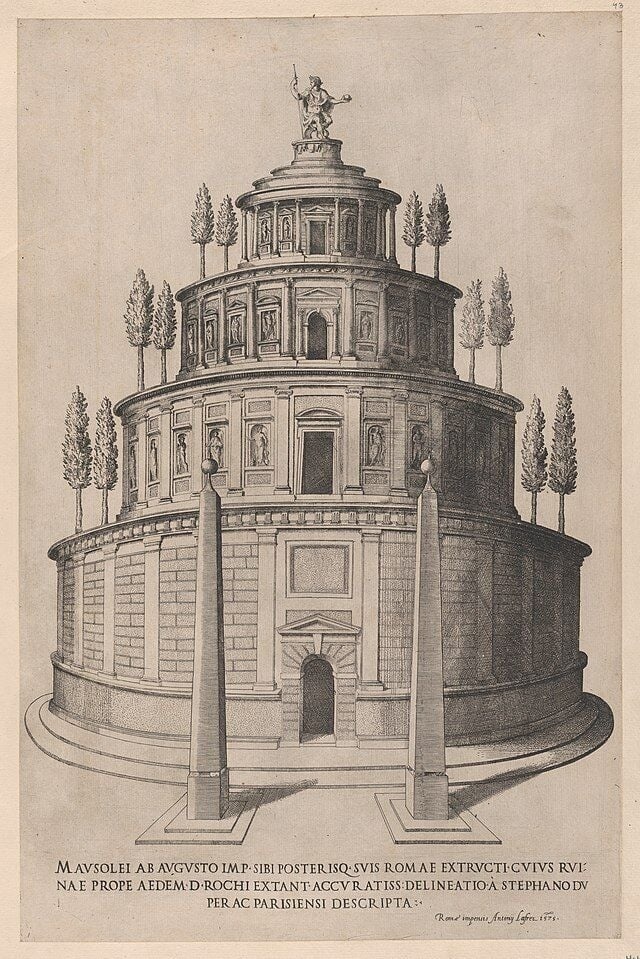

He Left a Legacy Cast in Stone

Augustus ordered the construction of many historically profound buildings while he was the ruler of Rome. Some of the most notable constructions that he initiated were the Temple of Caesar, the Baths of Agrippa, the Forum of Augustus, and the Mausoleum of Augustus.

The latter was where he was interred and was constructed as a resting place for all the honorable members of his family to be laid to rest. Augustus also started utilizing more marble in the structures he had erected. Prior to this, they used cheaper, less durable building materials. As such, Augustus’ final words to the public were, “I found Rome of clay, and leave her to you of marble.”

He Put on a Great Show for Rome

In history, it’s important for us to analyze what made a leader effective or ineffective and why. It is only through reflection that we are able to improve and avoid repeating mistakes of the past. If we consider how it came to be that Augustus seized and held power, it must be said that he stepped up at a point where Rome was in ruins.

He united nations that had been ravaged by civil war and gave the people a sense of stability by putting money and resources back into building the nation. This is all the more impressive if we consider that he struggled with sickness often. “Have I played the part well? Then applaud as I exit,” Augustus was said to have spoken on his deathbed. Bravo.

He Showed No Weakness

For an emperor to have power over a nation without being questioned on the difficult decisions, he can’t show signs of doubt. When he passed an order or issued a punishment, it had to be carried out, regardless of whether it was brutal or not. One such instance was a man who had received a death sentence for his crimes and implored the emperor to bury his corpse.

“The birds will soon settle that question,” was Augustus’ response. Another hard anecdote was the father and son who pleaded for their lives. The emperor suggested they ought to play a game of chance to decide who lives. After the father elected to forfeit his life for that of his child, his son killed himself.

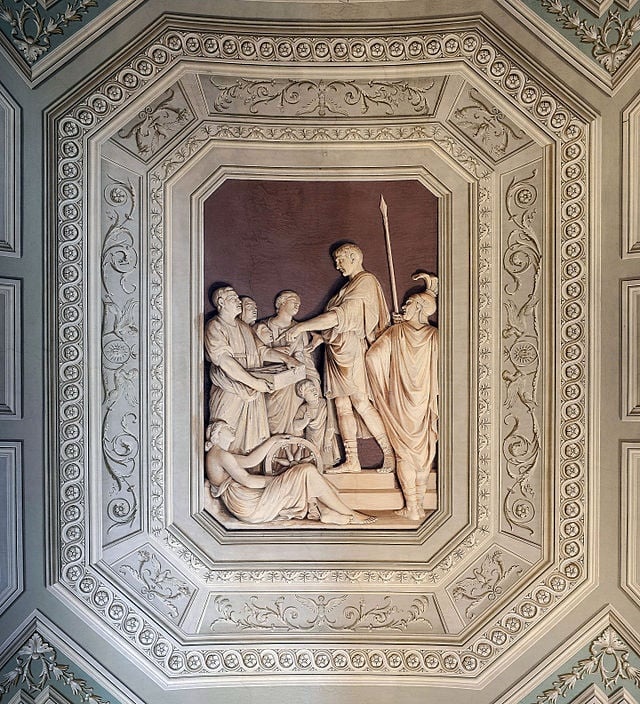

Blood Spilt to Commemorate Blood Spilt

Augustus had much respect for his great-uncle, and wouldn’t have been able to obtain his position in life if it wasn’t for Caesar. Caesar adopted him as his son and put him in the political position that launched him into power.

Aside from avenging his death, Augustus also held a memorial on the anniversary of the dictator’s assassination. He took 300 prisoners of war that had been captured in the Perusine War, and on the Ides of March (March 15), they were slaughtered on the altar of Caesar, in his memory.

Leave a comment