Overcoming Capitalist Constraints and Embracing Collective Potential

Sep 08, 2024

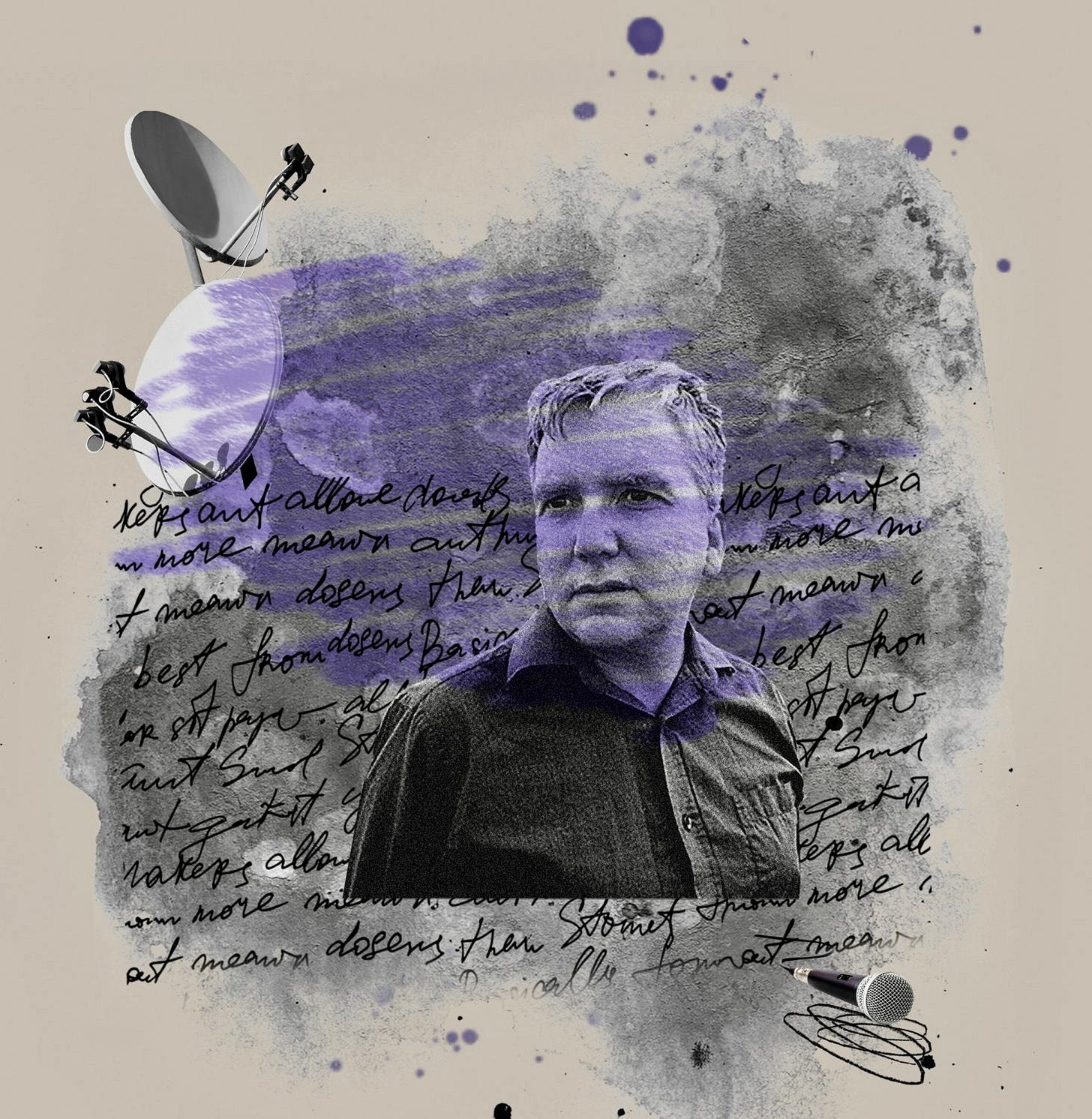

Reading and engaging with Mark Fisher’s work has been a journey of discovery, filled with a deep appreciation for the potential of radical new ideas. Fisher consistently emphasized the need to challenge the portrayal of capitalism as the only realistic or viable system.

In a time when capitalism’s grip seems all but unbreakable, Mark Fisher’s insights offer a refreshing critique and a path forward. Fisher’s examination of capitalist realism exposes a disturbing trend: mental health issues are frequently simplified to mere chemical imbalances, a perspective that masks their deeper social and political roots. This reductionist view not only frames mental illness as an individual issue but also serves capitalist interests by maintaining a profitable pharmaceutical market. However, Fisher didn’t stop with this critique. Drawing inspiration from Baruch Spinoza, he advocated for a profound shift in how we approach mental health and societal discontent through what he termed “psychedelic reason.” This concept urges us to explore the complex interplay between desire, capitalism, and political agency, emphasizing that true resistance involves recognizing and harnessing our collective capacities and potential.

Mark Fisher’s own struggles with mental health were not merely personal battles but became integral to his critique. His own experiences with depression and anxiety shaped his understanding of capitalist realism. He channeled his suffering into a deeper analysis of the systemic forces at play, articulating how the dominant ideology of “magical voluntarism” – the belief that one can overcome any obstacle purely through individual will – exacerbates feelings of helplessness. Fisher argued that this ideology, pushed by reality TV experts and business gurus, masks the structural causes of our diminished agency and reinforces a cycle of depression and powerlessness.

Fisher described magical voluntarism as both a cause and effect of low class consciousness, a reflection of the pervasive belief that individuals are solely responsible for their own misery. This ideological weapon creates an illusion of personal empowerment while perpetuating a sense of helplessness. It distracts from collective action and deepens our collective depression, leading to a paradox where the more we are told we can achieve anything, the more paralyzed we become by the disparity between promise and reality. Rebuilding class confidence, Fisher suggested, requires confronting this deliberately cultivated sense of individual failure and rediscovering our collective power to effect change.1

Thanks for reading Samridhi’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.Subscribe

Fisher’s innovative ideas and their philosophical roots offer more nuanced alternatives. By examining social and political dimensions of mental illness, Fisher’s work encourages us to look beyond individualistic approaches and engage with broader societal issues. This exploration aims to reveal pathways to a more mindful and connected existence, emphasising the importance of group consciousness and collective effort in navigating and addressing capitalist constraints.

Fisher’s connection to Spinoza resonates deeply with me, as Spinoza’s ethical reflections provide valuable insights into understanding capitalism’s complexities. I will draw on this connection throughout the discussion to offer a clearer perspective on the challenges we face.

The idea that “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism,” a notion articulated by thinkers like Fredric Jameson and Slavoj Žižek, captures what Fisher means by capitalist realism. It reflects the pervasive belief that capitalism is the only viable system, making it almost impossible to imagine a coherent alternative.

For Fisher, deliberately inducing a state of oblivion, whether through drugs or other means, played right into capitalism’s hands. It was akin to a Freudian compulsion, where individuals unconsciously reinforce the very structures that oppress them, much like a parasite that weakens but never fully destroys its host.

This realization uncovers the profound depth of Fisher’s thought. It’s exciting because it aligns with a project that has always intrigued me: How can we resist doing capitalism’s work for it? How can we raise our consciousness to not only escape capitalism’s influence but also to reshape our desires towards something beyond immediate self-gratification? Fisher’s work, tragically cut short, provides crucial insights into this ongoing struggle.

Fisher’s reflections on mental health, often shared on his K-Punk blog, also appear with casual brilliance in his writings:

“The current ruling ontology denies any possibility of a social causation of mental illness. The chemical-biological framing of mental illness aligns perfectly with its depoliticization. Viewing mental illness as an individual chemical-biological problem offers enormous benefits to capitalism. First, it reinforces capitalism’s drive towards atomistic individualization (you are sick because of your brain chemistry). Second, it creates a highly lucrative market for multinational pharmaceutical companies to sell their drugs (we can cure you with our SSRIs). It’s obvious that all mental illnesses have a neurological basis, but this says nothing about their causes. For example, if depression is associated with low serotonin levels, what still needs to be explained is why certain individuals have low serotonin levels. This requires a social and political explanation, and the task of repoliticizing mental illness is urgent if the left is to challenge capitalist realism.”

In this sense, Fisher’s blogospheric rallying cry was to argue that we already possess everything we need to escape the confines of capitalist realism—that ideological straitjacket that keeps us compliant and unimaginative. Drugs like acid or ecstasy might loosen the mind to some degree, but they neglect the more lucidly existential aspects of human subjectivity (our capacity to reason, our political agency), leaving them to rot and atrophy. Fisher argues that drugs are “like an escape kit without an instruction manual.” “Taking MDMA is like improving [Microsoft] Windows: no matter how much tinkering Bill Gates does, MS Windows will always be problematic because it is built on top of the rickety structure of DOS.” The drugs, then, are all too temporary—“using ecstasy will always mess up in the end because the Human OS [Operating System] has not been taken out and dismantled.” As fun as they may be, in the grand scheme of things, and as the old song goes, the drugs don’t work—they just make things worse.

Fisher envisioned a project grounded in what he called Spinozist “psychedelic reason,” seeking to uncover capitalism’s deeper mechanisms and explore meaningful alternatives.

But what exactly is this “psychedelic reason” rooted in Spinoza’s philosophy?

To explore this, we must consider Fisher’s final work, particularly his lecture series “Postcapitalist Desire,” designed for the 2016/17 academic year at Goldsmiths, University of London. In these lectures, Fisher examined the complex relationship between desire and capitalism, focusing on how desire can both aid and hinder our efforts to escape capitalism’s grip. He argued that the left’s current challenge lies in addressing how desire interacts with politics in a post-Fordist world. The decline of the Soviet bloc and the workers’ movement in the West wasn’t solely due to a lack of will or discipline. Rather, the disappearance of the Fordist economy and its disciplinary structures means that traditional forms of political organization no longer align with contemporary capitalism and the emerging subjectivities that either conform to or resist it. In simpler terms, the seductive appeal of consumer capitalism must be countered not by suppressing desire but by redirecting it towards more meaningful, collective goals.

However, capitalism’s remarkable flexibility has allowed it to absorb the disruptions brought about by technological and cultural change.

“If we are to take our psychedelic dream of emancipation seriously, and if it is to have any contemporary relevance whatsoever, we have to realize that nothing can be achieved by getting off your head on drugs,” Fisher argued. “This was not a moral point, but an acutely political one. The goal was, instead, ‘to get out through your head,’ by applying a ‘psychedelic reason,’ ‘auto-effecting’ your brain into a state of ecstasy.” Fisher drew on the 17th-century philosopher Baruch Spinoza, suggesting that this “psychedelic reason” is waiting to be rediscovered. Spinoza, whom Fisher called “the prince of philosophers,” is seen as crucial in exorcising the capitalist ego—a parasitic force of modernity—from our minds. Fisher noted that Spinoza “took for granted what would later become the first principle of Marx’s thought—that it was more important to change the world than to interpret it.” Spinoza sought to do this by constructing a reflective ethical project that was essentially a precursor to psychoanalysis, three centuries ahead of its time.

That is the one thing that helps me figure out if we can convert and channel our inner libido into not letting it be co-opted by capitalist forces and being subsumed under them. In the words of Francis ‘Befo’ Barcadi, we need to intervene and not only let the forces of total control take over politically while we remain the same socially. He beautifully captures the concept of insurrection, which can be deployed to mean using the resources of the body fully, in the autonomous act to go beyond desire.

Certain activities that help regain consciousness are those that align us with nature and help us take control of our breath. The goal is not to simply react to things as they come but to let our awareness expand beyond our immediate thoughts. This reflects evolutionary growth and what truly matters in the long term. We need to channel our libido into spaces where it does not do capitalism’s work for itself. This understanding helps us see capitalist ideology as stagnant and permanent. It’s not capitalism that needs to change, but our own awareness and adaptability. Fisher contrasts being with becoming, where being is seen as something continually in flux, striving to create and showcase the best that is possible.

In this context, breaking free from systems that continually attempt to define us is crucial. As I discussed in “The Practice of Freedom,”2 actively working to expand our consciousness involves a continuous effort to resist predefined identities and roles imposed by societal structures. The practice of freedom is about engaging in this ongoing work of self-expansion and resisting the limitations placed upon us by external forces. This is where group consciousness becomes crucial, demonstrating that overcoming capitalist forces requires collective effort. By supporting each other, we can resist the attempts by capitalist ideology to undermine and manipulate us.

Consciousness-raising involves continually expanding our understanding of both the self and the group, resisting the pull of rigid, fixated consciousness. Stepping out of one’s comfort zone and fostering an identity that embraces potentiality rather than constricting it is essential. This practice helps prevent the downward spiral of self-limitation and ridicule, allowing us to focus on the future potential of collective growth.

Ultimately, our goal should be to raise our level of consciousness, which is a challenging and sustained effort. We must move beyond immediate sensory pulls and the individualistic narrative pushed by patriarchy and capitalism. Resistance does not end at recognizing how things should change; it’s about capacities and potential. The proletariat has the potential to grasp this totality, while the bourgeoisie remains mired in ideology because it operates within a system that reinforces its own interests and suppresses the proletariat’s potential for consciousness-raising.

Mark Fisher and the Politics of Depression.” RS21, 27 Apr. 2014, http://www.rs21.org.uk/2014/04/27/kpunk/. Accessed 13 August 2024.

The Practice of Freedom

·

Jun 10

Subscribe to Samridhi’s Substack

Launched 4 months ago

🎓 Post-grad in Political Science | 📚 Teacher of Politics | 💬 Exploring crucial issues with an eye towards radical change. Join me.

Leave a comment