The second installment of the occasional feature in which I pose to all of you a question to which I genuinely want to learn the answer.

Nov 10, 2024

I really loved all the thoughtful responses you gave when I asked you, a couple of months ago, why American kids need to be in bed by 8pm. So we are once again opening this thread up for comment from everyone. But, to state the obvious, this topic could easily get a lot more heated. So here’s a friendly reminder: Be nice to each other. Engage in good faith. You can express robust disagreement in polite terms. If I get the sense that you’re stinking the place up, you’ll get banned—sorry.

And please do support my work—and get all my writing, plus ad-free access to full episodes of the podcast—by becoming a paying subscriber today.Subscribe

Donald Trump has won a decisive victory. It is now clear that 2016 was not an aberration. Among Democrats, the blame game has already begun.

Some fault the economy for Kamala Harris’ defeat. Others point the finger at Democratic positions on cultural issues. Others still, replaying the greatest cable news hits from 2016, have concluded that the American electorate must be racist or sexist or homophobic (or all of the above).

On the night of the election, I shared my own assessment for why Democrats, and the broader institutional ecosystem with which they are now closely associated, have become so deeply unpopular. I will write a lot more on the topic in the days and weeks to come, so please stay tuned. But it strikes me that there is a missing question in the debate, one which commentators—including me—might be avoiding in part because they have a less developed answer to it.

The Dawn of the Trump Era

·

Nov 5

According to polls, Donald Trump is not especially popular. Most Americans continue to believe that both he and the party he has shaped in his own image are too extreme. As Frank Fukuyama pointed out in our podcast a few days ago, there is also a genuine possibility that his administration will overreach in key respects, once again proving true the thermostatic theory of American politics according to which public opinion tends to move away from the sitting president.

BUT: It is also clear that Trump has a genuine appeal of his own. When he first entered politics, many political scientists explained him away as a representative of an aging, white electorate resentful about cultural and demographic change. And yet he owes Tuesday’s victory to his ability to attract new voter groups to the Republican Party—from Hispanics to union members to young men.

Even as Florida’s population has become far more diverse, for example, the state has undergone a remarkable evolution from the country’s most closely contested swing state to deep red territory. And while a lot of commentators have tried to explain this away by pointing to the presence of politically conservative refugees from Castro’s Cuba or Maduro’s Venezuela, the simple truth is that Hispanics have also swung to Trump in the overwhelmingly Mexican-American districts of southern Texas or the heavily Puerto Rican neighborhoods of New York City.

So I’d love to hear your thoughts on how Kamala lost. But I’d be even more grateful if you can help me answer the inverse question: Why did Trump win?

One more thing.

A lot of people are beating up on election forecasters like Nate Silver for failing to predict Trump’s victory. Pollsters should indeed ask themselves how they could underestimate Trump’s share of the vote for the third time in a row. But any attentive reader of the more sophisticated forecasters in the game should have known that Tuesday’s outcome was one of the likely scenarios. As Silver emphasized throughout, polls have historically been off by an average of about three points—and given how close the race looked in many swing states, a three point miss in one or another direction would likely hand a clear victory to either Harris or Trump.

That is pretty much exactly what happened. And so anyone who now claims that forecasters did not consider Tuesday’s results a realistic possibility has failed a simple test of reading comprehension.

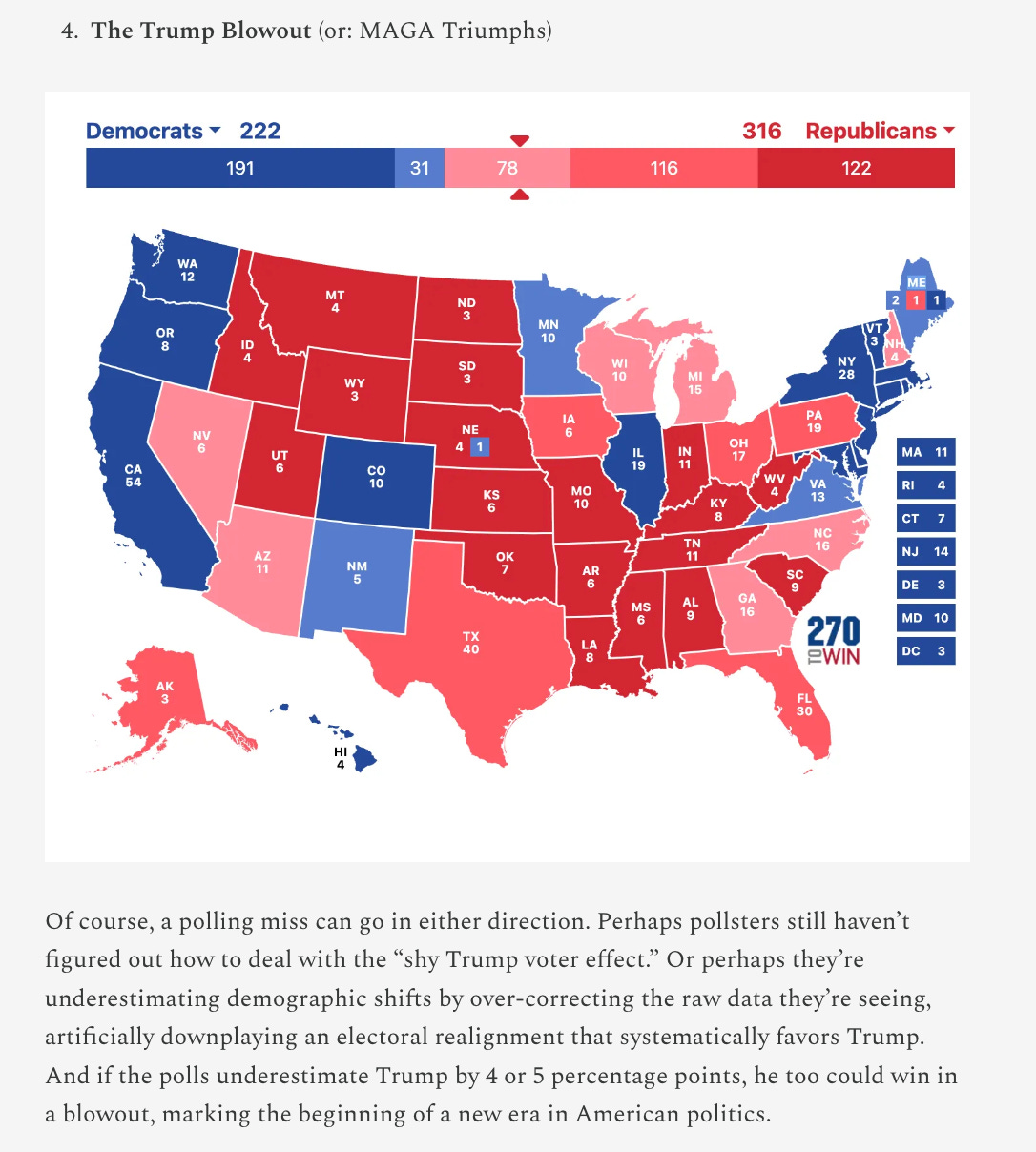

Need some evidence? Look at my post from last Sunday. I did not have a strong feeling about who would win, and basically wrote up what I learned from Silver and other forecasters. And yet, as one of the five worlds we might end up in, I published a map that is very close to the final result. (The only difference is New Hampshire, which might in my imagination have fallen to Trump in the event of a real blowout.)

Screenshot here:

Help Me Understand… Whether Wokeness Is the Fault of Moderates or Radicals

The third installment of the occasional feature in which I pose to all of you a question to which I genuinely want to learn the answer.

Dec 01, 2024

This series is quickly becoming one of my favorite parts of this Substack community! So I am once again opening this thread up for comment from everyone. As ever, a friendly reminder: Be nice to each other. Engage in good faith. You can express robust disagreement in polite terms.

And please do support my work—and get all my writing, plus ad-free access to full episodes of the podcast—by becoming a paying subscriber today.Subscribe

Many progressives continue to deny that the left’s embrace of identitarianism helped Donald Trump win the election. That is a key reason why, as I argued last week, it is unlikely that Democrats will let go of wokeness anytime soon.

But even among those who do accept the damage that identitarian rhetoric and policies have done to the Democratic brand, a fierce debate has broken out. Moderates and radicals are pointing fingers, with each claiming that the other is the real reason why the party has proven so susceptible to these ideas.

One side claims that it is radicals like the members of the Squad who have introduced wokeness to the Democratic Party. Like James Carville, they locate the origins of the problem in the “faculty lounge politics” of radical college professors and extreme activists.

Others retort that it is “corporate Democrats” like Hillary Clinton and Kamala Harris who have appropriated wokeness for their own purposes. Aaron Regunberg, for example, has insisted that “Dumbass forms of identity politics didn’t come from the Bernie wing of the Democratic Party.” Tyler Austin Harper struck the same chord: “Woke shit [that] centrists now say they hate,” he claims, “was first amplified by centrists attempting to paint Bernie as racially insensitive and insufficiently intersectional.”

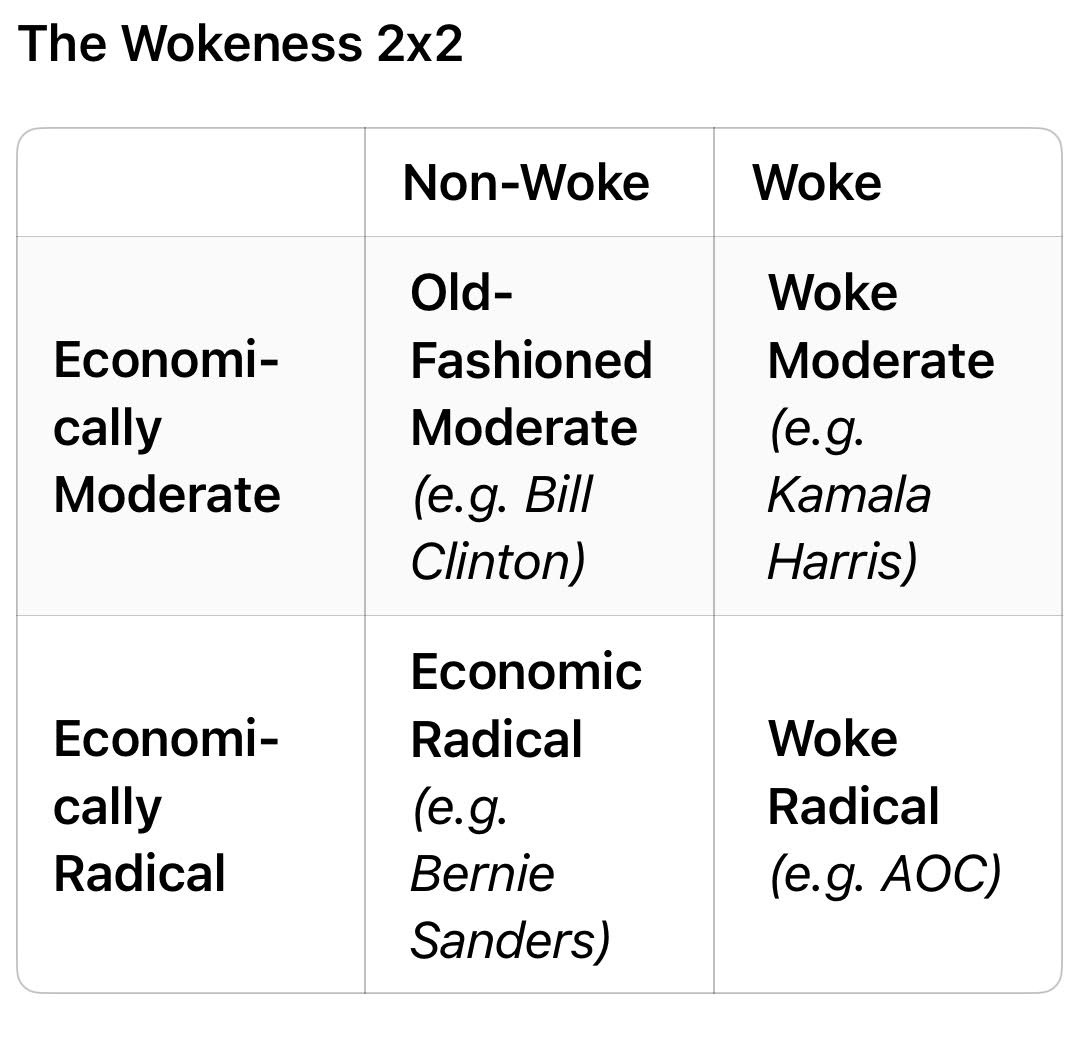

It seems to me that a humble conceptual tool can help to shed some light on this debate. Social scientists use the 2×2, which shows how a difference among two independent dimensions creates four distinct quadrants, so often that their fondness for it has become a running joke. But social scientists resort to 2x2s so often because they really can be clarifying. And what “The Wokeness 2×2” reveals is that there are four distinct camps within the left.

Left-wing politicians need to make two different choices: They either adopt identitarian attitudes on cultural issues which make how we treat people explicitly depend on the group into which they were born or stick to a more universalist (and often more class-conscious) framework for how to overcome discrimination and historical injustice. Separately, they either embrace the benefits of the market economy, arguing for meliorist policies like an expanded welfare state, or they oppose capitalism in a more fundamental way, perhaps going so far as to embrace the label of being a “socialist.” That results in four conceptual possibilities.

No living-and-breathing politician fits into a neat box, so labels for each of these camps are inescapably going to be somewhat simplistic. And yet, it seems to me that all four of these quadrants describe major political figures with real influence in the Democratic coalition:

- Old-fashioned moderates: These are politicians that are both politically and culturally moderate. Bill Clinton is the obvious example. Others who arguably fit the bill include Seth Moulton or Jon Tester or (depending on how you interpret his presidency) Barack Obama.

- Economic radicals: These are economic populists who often feud with moderate Democrats on economic questions but tend to prioritize questions of class over those of race. Bernie Sanders is an obvious example (at least if you focus on his 2016 campaign and discount his subsequent embrace of more identitarian aides and talking points). Though they are more economically moderate than Sanders, you could add politicians with a populist touch like Sherrod Brown and John Fetterman to the list.

- Woke moderates: These are establishment politicians who are close to the “corporate wing” of the Democratic Party but frequently use identity-based appeals or vocabulary to further their agenda. Kamala Harris is an obvious example. But you might add others like Gavin Newsome or Catherine Cortez Masto to the mix.

- Woke radicals: These are politicians who are radical on both the cultural and the economic dimensions. AOC remains the obvious example (though she has recently shown signs of moderating). Other members of the Squad, like Cori Bush and Ilhan Omar, also fit the bill.

Subscribe

This shows that the split about wokeness transcends the somewhat simplistic divide between moderates and radicals. There is resistance to wokeness both among moderates like Bill Clinton and among radicals like Bernie Sanders. Conversely, there are proponents of wokeness both among moderates like Kamala Harris and among radicals like AOC.

The fact that some moderate as well as some radical Democrats have embraced wokeness helps to clarify the terms of the debate. But it does not answer the substantive question. So… please help me settle the debate.

Who is more to blame for the rise of wokeness in the Democratic Party? Was it the woke radicals who succeeded in turning these fringe ideas mainstream? Was it the cynical embrace of these ideas by woke moderates that made them so dominant? Or do both wings of the party share equal responsibility?

Leave a comment