The author warns against the deification of Ambedkar by the right and by political parties cynically seeking the Dalit vote

Updated – December 10, 2024 10:57 am IST

Followers of Babasaheb Ambedkar pay homage on his death anniversary, in Dadar, Mumbai. | Photo Credit: Getty Images

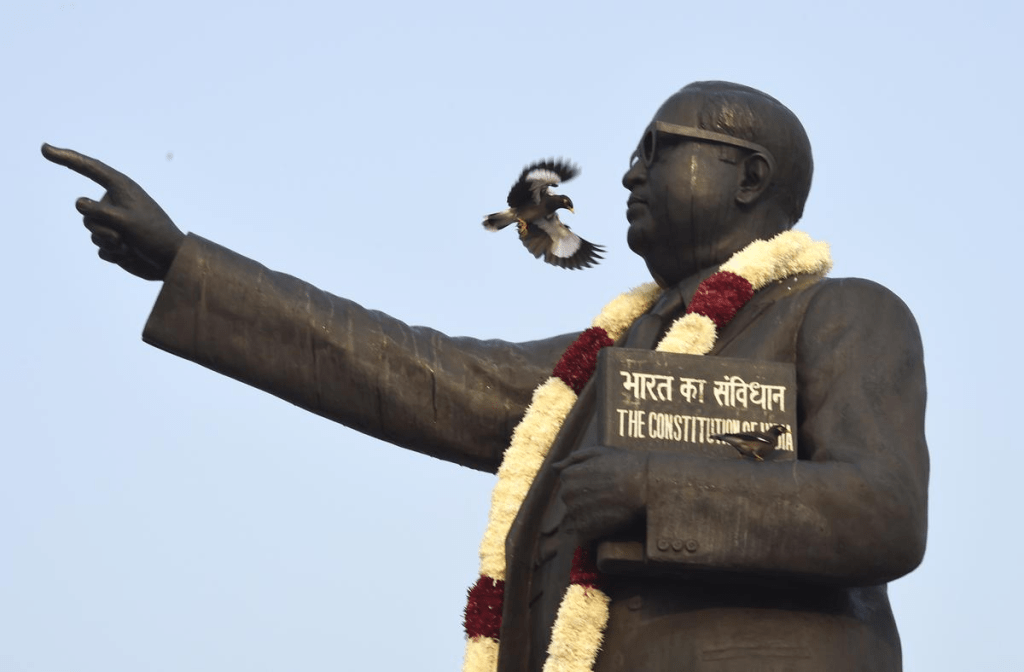

The most iconic image of Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar depicts him holding a copy of the Constitution. We know why this is so. But in 1953, during a debate in the Rajya Sabha, in response to a comment that he was the architect of the Constitution, he exploded: “I was a hack. What I was asked to do, I did much against my will… Sir, my friends tell me that I have made the Constitution. But I am prepared to say that I shall be the first person to burn it out. I do not want it.”

A statue of Ambedkar at Parliament House, New Delhi. | Photo Credit: Getty Images

Was this an isolated outburst, an anomaly? Not at all. He said it again in 1956, a few months before his death. Why did the man hailed as the father of India’s Constitution feel compelled to publicly disown it? And if Ambedkar was just a “hack”, then who were the real makers of the Constitution? Anand Teltumbde, a leading authority on Ambedkar and the Dalit movement, raises several such discomfiting questions in Iconoclast, a “reflective biography”.

Filtering a story

Teltumbde states upfront that he isn’t interested in “the pretence of presenting any new facts.” Rather, his objective as a biographer is to filter the story of Ambedkar’s life “through a sieve of rationality” so that people are awakened from what he describes as “their state of devotional inebriation”. Indeed, exploding the cultishness around Ambedkar is the driving force behind the author’s “comments, questions marks and discussions” that constitute the “reflective” dimension of this biography.

Ambedkar in Columbia University, in 1916. | Photo Credit: Wiki Commons

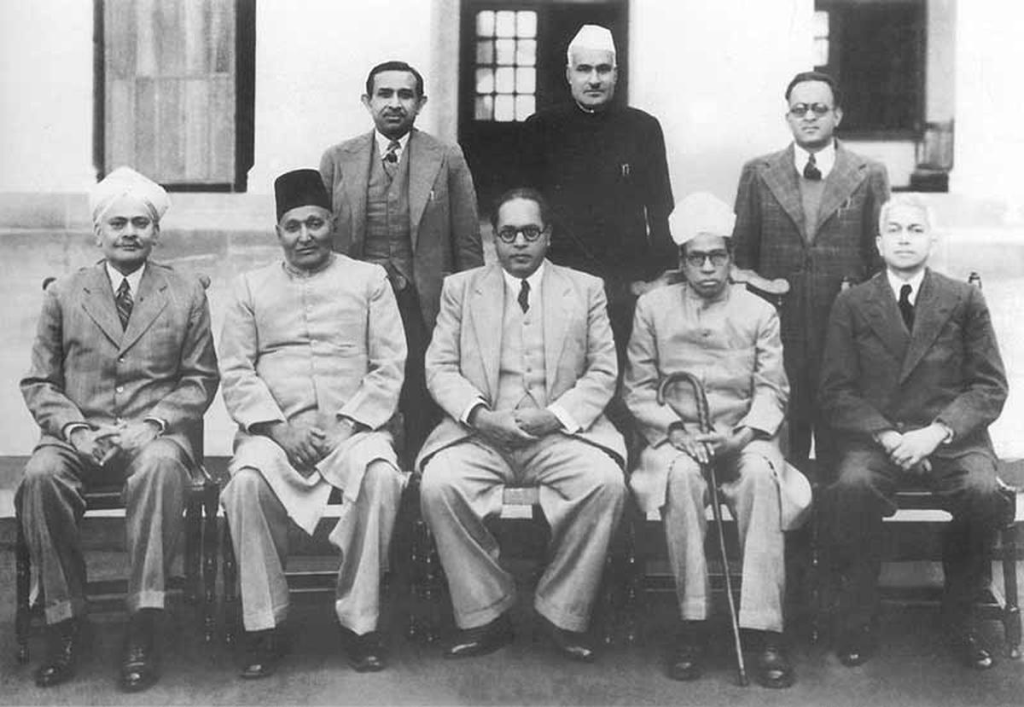

The biggest component of the Ambedkar iconography is his mythologised role as the architect of the Constitution, and Teltumbde has plenty to say on the subject, starting with how he got to be the chairman of the Drafting Committee — it was thanks to Gandhi and the Congress, two adversaries who have copped the most bitter of his many tirades. “It is only Gandhi who could see the strategic value of Ambedkar… for the longevity of the future constitutional State, which would be insured if a multitude of people, particularly its potential victims, especially upheld it… If Ambedkar, already a demigod for Dalits, is projected as the maker of the Constitution, the Dalits and potentially the entire lower strata, would emotionally defend it.”

Ambedkar as chairman, with other members of the Drafting Committee of the Constituent Assembly of India, on August 29, 1947. | Photo Credit: Wiki Commons

Not a free agency

Not surprisingly, Ambedkar did not enjoy much freedom as the chairman of the Drafting Committee. Teltumbde cites historian Granville Austin’s pioneering work to buttress the point that the Drafting Committee was never a free agency and that “every word that entered the Constitution was controlled by the Congress… led by an ‘oligarchy’ of Nehru, Rajendra Prasad and Maulana Azad.” This is a critical aspect to bear in mind when commentators, especially from the right, cherry pick self-serving quotes from Ambedkar’s speeches in the Constituent Assembly debates, especially on topics like secularism. As Teltumbde observes, in many of these debates, Ambedkar was not expressing his own opinions but ‘lawyering’ on behalf of the Congress-controlled draft amendments, which explains his ‘hack’ remark.

Babasaheb Ambedkar being sworn in as independent India’s first Law Minister by President Rajendra Prasad, in the presence of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, on May 8, 1950. | Photo Credit: Wiki Commons

The ‘real’ Ambedkar, as Teltumbde shows in this meticulously researched book, was a man of contradictions, a flawed individual who made errors of judgement, and did not always transcend the prejudices of his time, all of which not only do not detract from his greatness but rather add to it by rendering him as an all too human figure that ordinary people could relate to.

Pictures of Ambedkar being sold at an event in Noida. | Photo Credit: Getty Images

‘Too Mahar-centric’

Speaking of Ambedkar’s errors of judgement, Teltumbde is most unforgiving about his eschewal of class politics and the Mahar-centricity of the various institutions he set up, which also explains his failure as a builder of organisations. He attributes Ambedkar’s “strategic incoherence” to the deep influence of John Dewey’s pragmatism, which left him forever in experimental mode. This led him to dally with diverse ideological streams — from Fabianism and socialism to pragmatism and a version of Marxism-inflected Buddhism. The bottom line: no clarity on what exactly constitutes ‘Ambedkarism’, not that he intended any ‘ism’ as his legacy.

Teltumbde laments that the identitarian animus of today’s Ambedkarites is directed “not against the Brahminic zealots… but against Marxists and communists”. He is amazed that despite Ambedkar’s warnings about the moral sickness of Hindutva politics, there are so-called ‘Ambedkarites’ even in the Sangh Parivar camp. Their justification? “They invoked the pragmatic Ambedkar who in order to secure safeguards for Dalits gave up his lifelong antagonism with the Congress”.

People offer floral tributes on the occasion of Ambedkar’s birth anniversary, in Noida. | Photo Credit: Getty Images

What would an impartial assessment of Ambedkar’s legacy look like? Of course, no assessment could possibly be harsher than Ambedkar’s own, for he believed he had failed to achieve his goal of securing a political future (separate electorates) and social guarantees for Dalits. For Teltumbde, however, it is the iconisation that is the most problematic element of his legacy, for it has not only “deradicalised” him but has also “led to the competitive allurement of Dalits by all political parties using the Ambedkar icon as a proxy… disorienting the Dalit masses further into an identitarian morass.” In such a political scenario, a radical praxis inspired by Ambedkar’s life (as opposed to ‘Ambedkarism’) demands breaking through the iconisation to connect with the Ambedkar of flesh and blood, the breaker of chains, the mocker of traditions, the iconoclast. For those keen on such an intellectual and political project, this book is an invaluable resource.

Iconoclast: A Reflective Biography of Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar; Anand Teltumbde, Penguin/Viking, ₹1,499.

sampath.g@thehindu.co.in

Published – December 09, 2024 11:00 am IST Read CommentsREAD LATERPRINT

Leave a comment