Decoding Da Vinci

and

Dec 14, 2024

Few works of art have sparked as much intrigue and debate as Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper. It has inspired awe for centuries — not only for its artistry, but for the layers of symbols and messages concealed within.

What secrets lie in the shadow of Judas’s betrayal? How does Christ’s calm demeanor hold firm against the storm of human emotion? And is there any truth to Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code?

Today, we break apart all of these questions — and reveal what makes The Last Supper one of the most enigmatic and enduring masterpieces of all time…

Reminder: this is a teaser of our Saturday-morning deep dives.

Upgrade to get the full articles, exclusive interviews, and members-only podcasts every weekend — and help support our mission! 👇Subscribe

A Theatrical Drama

Many are not aware that it’s actually a mural, painted on the wall of a church refectory in Milan. Leonardo was working for Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan, who wanted the popular subject of the Last Supper painted in the monks’ dining hall.

Leonardo took far longer to finish it than Ludovico had liked, but when he finally unveiled it, it was clear why — this was no ordinary Last Supper scene, but one of the most enthralling narratives ever painted.

Leonardo’s version was a drastic break with tradition. While earlier depictions show Christ calmly dispensing bread and wine, Leonardo chose a different focus — the precise moment that Christ announces:

“One of you will betray me.”

This revelation sends shockwaves through the Apostles, each reacting in their own unique way. The scene is alive with motion and emotion: hands gesturing, faces contorted, bodies leaning in or recoiling in a scene of masterfully choreographed drama. Yet at the center of this chaos is Christ, serene and composed.

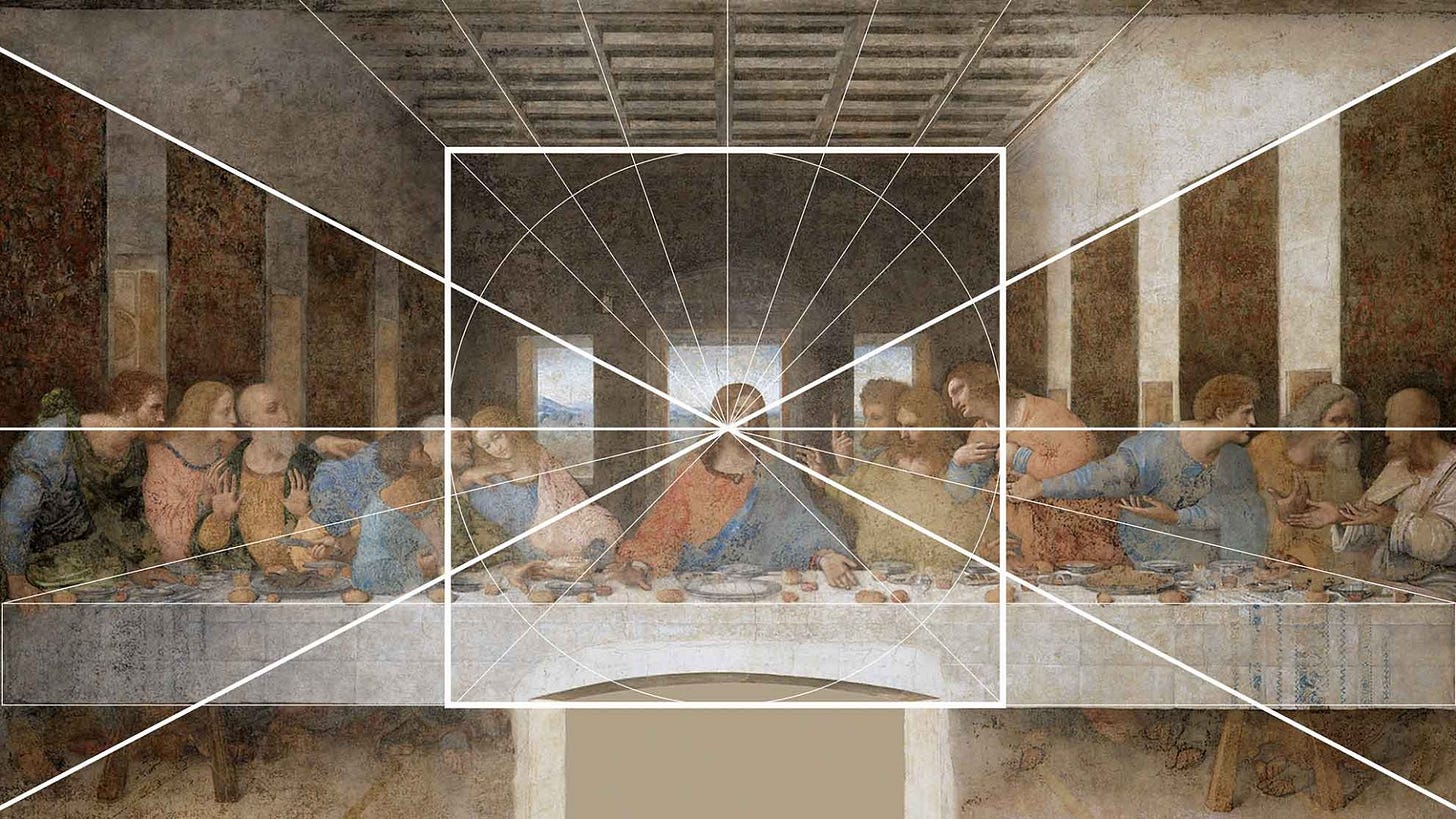

The composition further amplifies this dynamic tension. The Apostles are grouped into sets of three, their gestures and positions carefully arranged to create a visual path that leads the viewer’s eye toward the center.

Leonardo’s use of linear perspective — a hallmark of Renaissance art — further emphasizes this focal point, with the architectural lines of the walls and ceiling converging around Christ’s serene figure.

In the midst of human chaos, Jesus remains the embodiment of divine calm. His body even forms a triangular shape — Leonardo’s way of symbolizing the Holy Trinity and emphasizing Christ’s divine centrality in the composition.

Remember, as ever with Leonardo’s work, not a single detail is accidental…

Hidden Symbols and Controversies

To give a sense of the symbolic depth of the painting, notice each Apostle’s reaction is layered with meaning:

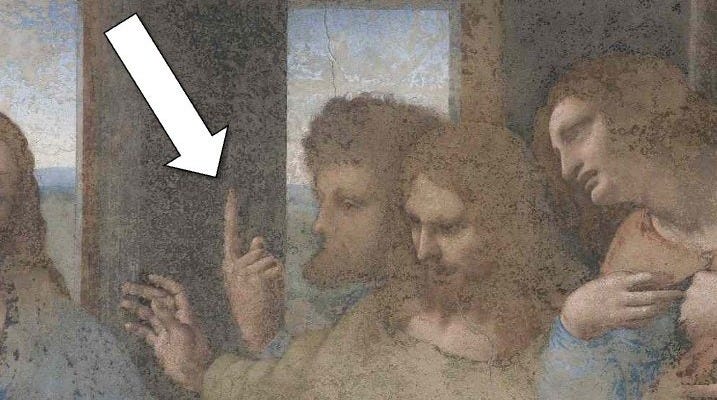

Saint Peter clutches a knife, foreshadowing both his defense of Christ during his arrest and Judas’s demise. Saint Thomas raises a single finger, a curious gesture that recalls his later demand for proof of Christ’s resurrection. Some even speculate that Thomas’s pose — skeptical yet curious — may be a self-portrait of Leonardo himself.

Then there is Judas. Seated slightly apart from the others, he leans back aghast, clutching the silver coins he received for his betrayal. A tipped-over salt container sits in front of him, a symbol of his broken covenant with God.

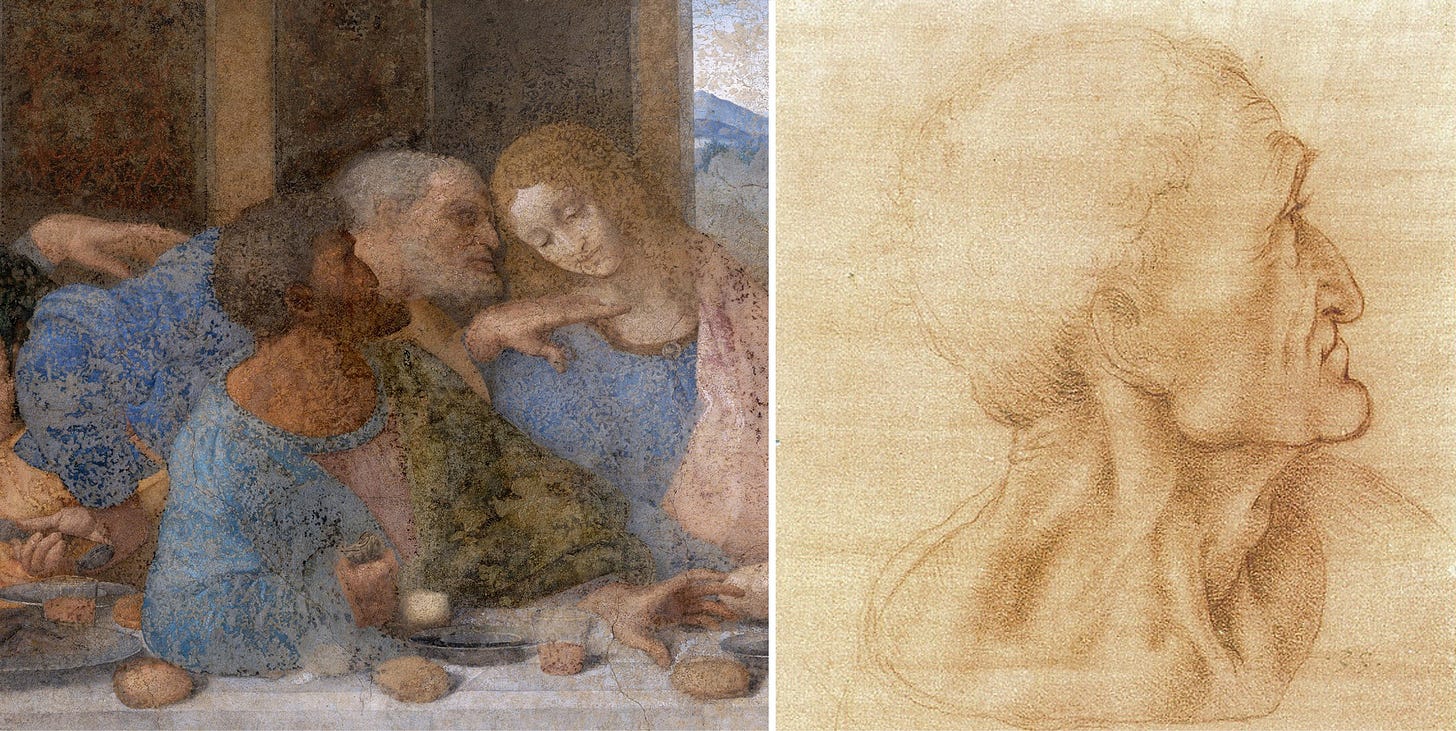

Leonardo took great care to make Judas the ugliest in the room. He searched long and hard for the ugliest model he could find, and his appearance contrasts him starkly with Christ’s idealized visage.

Yet arguably the most contentious figure in the painting is the one seated to Christ’s right. Some claim this is Mary Magdalene, the female follower of Jesus present at both the crucifixion and burial, but about whom relatively little is known. Proponents of this theory point to the figure’s feminine appearance, an idea made extremely popular by Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code.

However, art historians argue that it must be Saint John, traditionally depicted in Renaissance art as feminine to accentuate his youthful, gentle nature. Moreover, if it were in fact Mary Magdalene, then the absence of John elsewhere in the painting would be without precedent — no other depiction of the Last Supper omits him.

These theories feed into the idea of Leonardo as a great skeptic of Christianity and quintessential Renaissance rebel, secretly embellishing commissioned religious works with his personal jabs at the faith.

Another such theory points to the lack of halos above the characters’ heads — clearly unusual for a Last Supper depiction of the time, and often interpreted as carrying Leonardo’s skepticism about Christ’s divinity.

But this conclusion severely underestimates Leonardo’s subtle brilliance. Look closer and you’ll realize Christ is framed not by a traditional halo, but by the light of the central window — a kind of natural halo.

What might that imply?

Leave a comment