Trump’s sentence in New York — no prison, probation or fines — solidifies the declining role of legal accountability in our politics.

January 10, 2025 at 4:50 p.m. ESTYesterday at 4:50 p.m. EST

4 min106

Analysis by Aaron Blake

The criminal sentencing of President-elect Donald Trump on Friday was not how most who wanted to see him held criminally accountable envisioned an end to his legal battles.

Trump, who was convicted in New York on 34 felony counts of falsifying business records to pay hush money to adult-film actress Stormy Daniels, wound up escaping any real punishment. Because his election has made punishing him impractical, the president-elect was sentenced to an “unconditional discharge.” This means he will face no prison time, probation or even fines.

Get the latest election news and results

The sentencing did solidify that Trump will enter office in 10 days as a felon, but that’s about it. Trump’s three other criminal cases have effectively been killed off by his election.

But, ultimately, the non-sentence was a fitting ending — at least politically speaking. The American people did largely think Trump was a criminal, which he now officially is. They also didn’t seem to really want to have him punished for that, and now he won’t be.

The anticlimactic judicial decision epitomizes something that has become increasingly evident in the Trump era: The courts, which so many people have hoped would prove a bulwark against Trump, have now been relegated to a cog in our political system — subject to much of the same political gamesmanship, polarization and disregard as everything else. And Trump played that game to his advantage in the end.

The biggest consequence of Trump’s criminal cases, after all, appears to be that Trump will now enjoy a larger degree of immunity in his second term than he did in his first. The Supreme Court gave him that thanks to legal proceedings in another case.

Polling showed how conflicted and nuanced American views were about Trump’s legal troubles.

Despite Trump’s claims of legal persecution, it generally showed Americans didn’t subscribe to that. When the verdict in New York came down, Americans approved of it and thought Trump was guilty — often by double-digit margins.

Even after the 2024 election, a CNN poll showed Americans said by a 54-45 margin that they disapproved of special counsel Jack Smith dropping the federal criminal charges against Trump (something Smith had little choice about, given Justice Department policy against prosecuting a sitting president).

Americans elected Trump, but at least some of his voters also still wanted him prosecuted.

Americans also didn’t want Trump to go to prison for his crimes in New York. Only about 4 in 10 subscribed to that view. And while a pre-election CNN poll showed 51 percent of Americans said Trump’s criminal charges were a reason to vote against him — vs. just 12 percent who said they were a reason to vote for him — many Trump supporters were voting for him anyway. Fully, 7 percent of Trump supporters said the charges were a net-negative in their voting calculus, but they were backing Trump anyway. That was more than enough to swing the election his way.

In other words, the most crucial voters thought Trump’s criminal cases were more of a political data point than anything else. People were willing to believe Trump was a criminal and factor it into their votes, but that’s about all his legal troubles amounted to for them, politically.

But that, too, is a significant moment for our democracy. Whatever you thought of the criminal cases brought against Trump, the fact that Americans generally agree with the New York courts that he is a felon but it’s not a big enough deal to keep him out of office dilutes the power and force of our legal system. No longer is a felony conviction — even a justified one — disqualifying in the minds of Americans.

You could argue that a conviction in one of Trump’s other cases would have landed with more force, given polls showed Americans were much more concerned about his conduct in them than in the relatively small-bore hush money case. And perhaps that’s true — especially for Trump’s classified-documents case, the most legally problematic of all of his cases, and the one casual voters were probably the most unfamiliar with.

But the practical effect of all of this is that cases like that will be much less likely to be brought in the future — both because of how Trump skirted these charges and made life hell for those prosecuting him, and because presidents will now enjoy a significant degree of immunity moving forward.

That’s the real-world legacy of these criminal cases, whether it’s an appropriate one or not.

Share106Comments

By Aaron BlakeAaron Blake is senior political reporter, writing for The Fix. A Minnesota native, he has also written about politics for the Minneapolis Star Tribune and The Hill newspaper.follow on X@aaronblake

Donald Trump Sentenced In Historic New York Hush Money Trial

Trump received a sentence of unconditional discharge — no punishment — but the 47th president of the United States will be a convicted felon.

By Sara Boboltz

Jan 10, 2025, 08:32 AM EST

|Updated 9 hours ago

[Music]

00:03

01:01

NEW YORK — President-elect Donald Trump received a sentence of unconditional discharge — or effectively no punishment — at a Friday hearing with New York Supreme Court Judge Juan Merchan, which puts an end to his hush money trial more than seven months after his unprecedented conviction.

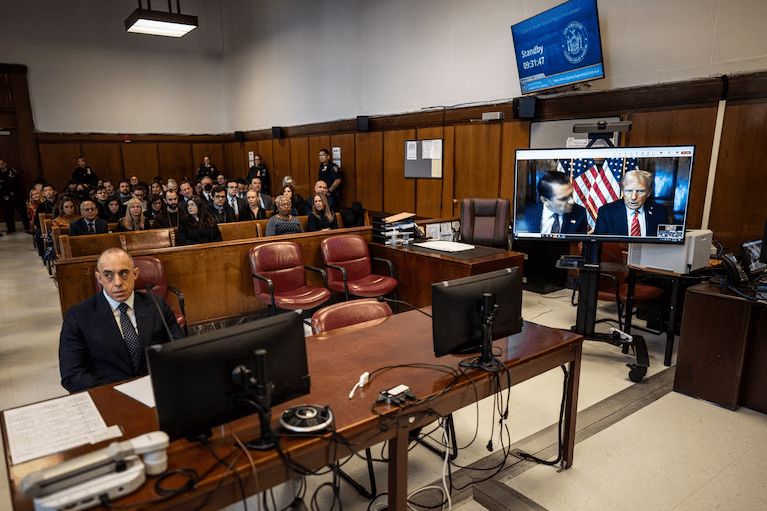

Trump appeared in court on a video feed from Mar-a-Lago, his Florida club, wearing a red and white striped tie and a frown. He was seated alongside his attorney Todd Blanche, with U.S. flags in the background.

Trump initially allowed Blanche to speak for him, averting his eyes from the camera. But he took the opportunity to address the court when Merchan offered it to him.

“This has been a very terrible experience. I think it’s been a tremendous setback for New York and the New York court system,” Trump said. “It was done to damage my reputation so I’d lose the election, and obviously it didn’t work.”

He added that he was “totally innocent” and “did nothing wrong.”

Trump pledged to “appeal this Hoax” in later remarks on his Truth Social platform.

While the judge and prosecutors ultimately agreed that presidential immunity protects Trump from any serious punishment given the circumstances, his sentence means that he’ll remain a convicted felon as he takes office later this month. Merchan acknowledged as much as he handed down the decision.

“This court has determined that the only lawful sentence that permits entry of a judgment of conviction without encroaching the highest office in the land is an unconditional discharge,” Merchan said. “Therefore, at this time, I impose that sentence to cover all 34 counts.”

The judge wished Trump luck with his second presidential term before dismissing him.

The extraordinary case reached a high-water mark in May last year, when a panel of a dozen New Yorkers found Trump guilty unanimously.

However, his original sentencing date — July 11 — was delayed by a U.S. Supreme Court decision expanding the definition of presidential immunity. The landmark ruling allowed Trump’s team to lob new defenses against the prosecution and, critically, delay his sentencing until after the election.

Trump’s attorneys fought the case tooth and nail every step of the way, arguing repeatedly to have it thrown out. Last month, attorneys Blanche and Emil Bove laid out an 80-page argument that continuing the proceedings would be a distraction for their client, impeding both his presidential transition and his ability to serve as president.

Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg, who brought the case, argued in turn that Trump’s conviction must stand in the interest of justice. But Bragg conceded that jail time was no longer practical given Trump’s imminent return to the White House.

Trump was never likely to serve a long time behind bars given he was convicted on low-level felonies and has no previous criminal record. He faced a maximum penalty of four years’ imprisonment.

Merchan determined that, contrary to Trump’s claims, the period between his election and inauguration on Jan. 20 afforded him no special protections; rather, presidential immunity would kick in the moment he took the oath of office. And so last week, the judge ordered Trump to appear for sentencing — virtually, if he liked.

Bragg’s hush money case seemingly constitutes the only criminal charges to stick to Trump thus far, although it could still be overturned on appeal. Two federal cases — one for Trump’s role in the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection and another for allegedly mishandling classified documents — were discontinued after his election. Another state-level case, in Georgia, has stalled amid allegations of prosecutorial misconduct.

Trump’s eleventh-hour appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court to stop his sentencing failed Thursday, as five out of nine justices agreed that the planned sentence of unconditional discharge was a relatively insubstantial burden for him to bear.

The Hush Money Scheme

Trump’s trial centered on a payment made to silence claims of an alleged affair in the final, chaotic days of the 2016 presidential election. But the criminal element was all in the cover-up.

Over the course of around five weeks’ worth of witness testimony, prosecutors showed the jury how Trump’s then–personal attorney, Michael Cohen, wired $130,000 to porn actor Stormy Daniels because she was threatening to tell a magazine that she had sex with Trump during a Lake Tahoe golf championship in 2006.

Cohen fronted the money. At the time, Trump’s campaign was teetering on collapse in the wake of the “Access Hollywood” scandal. The Washington Post had obtained a recording of Trump telling one of the show’s hosts, Billy Bush, that his fame permitted him to sexually assault women without consequence. Trump would survive the scandal — as he has survived many others since — but at the time, it was far less clear whether he would.

Cohen hounded Trump for repayment, both for the hush money and other campaign-related expenses totaling $150,000. Along with Trump Organization CFO Allen Weisselberg, the trio ultimately settled on a plan for Trump to reimburse Cohen in monthly installments over the course of his first year in the White House.

On official business records, the payments were described as legal expenses.

Bragg’s office successfully argued that was wrong. The true purpose of the repayments, prosecutors said, was to influence the 2016 presidential election by preventing unsavory information about Trump from getting out to voters.

A Parade Of Colorful Witnesses

Much of the trial’s witness testimony painted a portrait of Trump when he was less a fixture of national politics and more a fixture of the National Enquirer.

Trump had long palled around with the tabloid’s publisher, American Media Inc. CEO David Pecker, who testified that he was Trump’s “eyes and ears” during his first presidential run. Pecker published negative stories about Trump’s enemies, glowing stories about Trump himself, and he let Cohen know when somebody was shopping a harmful story around to magazines. The concept of “catch and kill” — “catching” a story by buying the rights and “killing” it by never publishing — was key to the case.

At the time, Cohen was still Trump’s faithful sidekick, howling curse words at anyone who did wrong by his boss. Some of the trial’s most emotional testimony came when Cohen took the stand to describe how he eventually decided to turn on Trump, after the FBI tore apart his home and office looking for evidence of the hush money payment in 2018.

“My wife, my daughter, my son all said to me: ‘Why are you holding on to this loyalty? What are you doing?’” Cohen testified. “It was about time to listen to them.”

Other people who took the stand included young former White House staffers who were around when Trump signed Cohen’s checks, and publishing house representatives who shared excerpts from Trump’s books illuminating how closely he oversaw his expenses.

Doubtlessly the most salacious testimony shared at trial came from Daniels.

Although prosecutors discouraged the porn actor from giving too many details of her alleged sexual encounter with Trump, she veered into the weeds more than once, going so far as to reveal which position the two used for sex.

Among her other recollections: Trump said Daniels reminded him of his daughter, he talked about himself until she told him he was being rude, and he did not wear a condom. Daniels said she felt coerced into sex, although she emphasized how she does not consider herself a victim.

Trump Hits Back, But Not From The Stand

A gag order prevented Trump from expressing the full extent of his anger toward Cohen, Daniels, prosecutors and other figures during the trial, as Merchan sought to shield them from harassment by Trump’s supporters.

Much of what he did say publicly was not true. Trump has claimed at varying points that because one of the prosecuting attorneys recently worked for the Justice Department, it meant that President Joe Biden had a direct hand in Bragg’s case, which is false. He claimed, falsely, that every prominent legal scholar in the country agreed with him that the case was “illegitimate,” “nonexistent” or “fake.” He also said that his gag order barred him from criticizing Merchan when it did not — Merchan specifically left himself off the list.

At one point, Trump was held in contempt of court and fined $9,000 for attacking people or subjects that were covered by the gag order. Trump posted less frequently to social media about the trial after that.

Still, every day, he left the courtroom to stand in front of cameras set up in the hall and rant about the proceedings.

The one place he did not speak was on the witness stand.

Trump, amid much speculation, opted not to testify in his own defense during the trial.

He was under no obligation to do so; it arguably would have been disastrous.

Trump gets an ‘unconditional discharge’ in hush money conviction − a constitutional law expert explains what that means

Published: January 9, 2025 7.36pm GMT Updated: January 10, 2025 4.01pm GMT

Author

- Wayne Unger Assistant Professor of Law, Quinnipiac University

Disclosure statement

Wayne Unger does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Donald Trump is now a convicted felon, and will be the first president of the United States with a felony conviction.

On Jan. 10, 2025, Justice Juan Merchan, who presided over the trial in a New York state court, sentenced Trump to an unconditional discharge for all 34 felony counts of falsifying business records in the first degree. In his statement to the court, Trump maintained the point he had made throughout the prosecution, that the whole case was a political witch hunt.

“The fact is, I’m totally innocent,” said Trump via a video appearance in the court.

During the sentencing, Merchan said he was keenly aware of the unique set of circumstances before him and the country. He characterized the trial as ordinary while acknowledging the context of the case was extraordinary.

“Never before has this court been presented with such a unique and remarkable set of circumstances,” said Merchan.

The sentencing brings this phase of the case to an end. Once the sentence is officially entered in a final judgment, Trump can appeal the case, as he has a legal right to do so. Trump’s attorney, Todd Blanche, made clear during the sentencing that Trump intends to appeal.

Trump ultimately failed to block sentencing

On May 30, 2024, a New York County jury found Trump guilty on 34 counts of falsifying business records in the first degree. That constituted a Class E felony in the state of New York, when the falsification is committed with an intent to defraud, commit another crime, or to aid or conceal the commission of another crime.

Class E felonies carry a potential penalty of up to four years in prison and a fine up to $5,000 for each count. Trial courts reserve discretion, however, to impose a sentence that accounts for other factors, such as the defendant’s criminal history.

In recent court filings, Trump sought to get his guilty verdict thrown out, arguing that the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent decision on presidential immunity in criminal prosecutions meant he can’t be found guilty.

On July 1, 2024, the U.S. Supreme Court had concluded that the Constitution provides “absolute immunity from criminal prosecutions for actions within his … constitutional authority.” The court had also concluded that presidents hold “at least presumptive immunity from prosecution for all his official acts” and “no immunity for unofficial acts.”

To be clear, Trump was convicted of unlawful conduct that occurred before his first term as president. And while it appears that the Supreme Court’s July 1 ruling applies to both state and federal criminal prosecution, the court held there is no immunity for unofficial acts, which the falsification of business records undoubtedly is.

On Jan. 3, 2025, Justice Merchan rejected Trump’s argument regarding presidential immunity because the Supreme Court’s immunity decision is not applicable in Trump’s New York case.

On Jan. 9, 2025, New York’s highest court declined to block Trump’s sentencing. The U.S. Supreme Court late in the same day denied Trump’s emergency bid to halt the sentencing, saying in its order that “the burden that sentencing will impose on the President-Elect’s responsibilities is relatively insubstantial in light of the trial court’s stated intent to impose a sentence of ‘unconditional discharge’ after a brief virtual hearing.”

Indeed, Merchan had expressed little willingness to impose prison time for the president-elect. In the order rejecting Trump’s presidential immunity argument, Merchan said, “It seems proper at this juncture to make known the Court’s inclination to not impose any sentence of incarceration.”

Even if Merchan imposed prison time, many constitutional law scholars, including myself, argue that Trump’s sentence would, at minimum, be deferred until after his next term in the Oval Office.

Rather, Merchan imposed “unconditional discharge” as a sentence. That means there are no penalties or conditions imposed on Trump, such as prison time or parole.

Serving the public interest, not time

According to New York law, a court “may impose a sentence of unconditional discharge … if the court, having regard to the nature and circumstances of the offense and to the history, character and condition of the defendant, is of the opinion that neither the public interest nor the ends of justice would be served by a sentence of imprisonment and that probation supervision is not appropriate.”

Regarding Trump’s case specifically, Merchan wrote, “A sentence of an unconditional discharge appears to be the most viable solution to ensure finality and allow (Trump) to pursue his appellate options.”

Put simply, it appears Merchan, having considered the totality of the circumstances, including Trump’s election to a second term as president, concluded, as is his right as a judge, that it is in the best interest of the public not to imprison Trump.

Generally, trial courts reserve a tremendous amount of discretion when it comes to imposing sentences. Legislatures can, and often do, set sentencing guidelines, prescribing what penalties trial judges can impose. It is clear in this case that the New York State Legislature allows trial judges to, at their discretion, deliver “unconditional discharge” as a sentence.

Uniquely, Trump had sought dismissal of his guilty verdict before his sentencing. Normally, criminal defendants do not have a legal right to appeal their verdicts until a final judgment is entered against them. In criminal law, a final judgment must include the defendant’s sentence.

But, of course, this is not your ordinary criminal case. As Merchan hinted, moving forward with the sentencing favored Trump because it would result in a final judgment being entered against him, thus enabling him to properly appeal his conviction.

This story has been updated to reflect the U.S. Supreme Court’s order denying Donald Trump’s bid to delay his Jan. 10 sentencing and to include the actual sentence entered against Trump.

- Criminal justice

- US Supreme Court

- Donald Trump

- Presidential immunity

- Donald Trump trials

- Judge Juan Merchan

Before you go …

90,000 experts have written for The Conversation. Because our only agenda is to rebuild trust and serve the public by making knowledge available to everyone rather than a select few. Now, you can receive a curated list of articles in your inbox twice a week. Give it a go?

Get our newsletter

Leave a comment